Contemporary Research

Models, Methodologies, and Measures in Distributed Team Cognition

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Contemporary Research

Models, Methodologies, and Measures in Distributed Team Cognition

About this book

The objective of Contemporary Research: Models, Methodologies, and Measures in Distributed Team Cognition is to advance knowledge in terms of real-world interactions among information, people, and technologies through explorations and discovery embedded within the research topics covered. Each chapter provides insight, comprehension, and differing yet cogent perspectives to topics relevant within distributed team cognition. Experts present their use of models and frameworks, different approaches to studying distributed team cognition, and new types of measures and indications of successful outcomes. The research topics presented span the continuum of interdisciplinary philosophies, ideas, and concepts that underline research investigation.

Features

-

- Articulates distributed team cognition principles/constructs within studies, models, methods, and measures

-

- Utilizes experimental studies and models as cases to explore new analytical techniques and tools

-

- Provides team situation awareness measurement, mental model assessment, conceptual recurrence analysis, quantitative model evaluation, and unobtrusive measures

-

- Transforms analytical output from tools/models as a basis for design in collaborative technologies

-

- Generates an interdisciplinary approach using multiple methods of inquiry

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Situation Awareness in Teams

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

- (1) Level 1 SA—The perception of key information relevant to the decision maker’s needs. This may include the direct perception of information when the individual is embedded directly in the world (e.g. an infantry solider observing enemy movement or a pilot observing relevant terrain), but also often involves the receipt of information from other team members via verbal or nonverbal communications, written reports, and electronic information displays (Endsley, 1995a, 1995b). Thus, it includes information from natural, engineered, and human sources. For example, an air traffic controller who receives information from a controller in an adjacent sector or from an aircraft pilot is obtaining relevant information from other team members that is then compared to and combined with information from other sources.

- (2) Level 2 SA—The comprehension or understanding the significance of that information with regard to the decision makers’ goals. SA involves knowing more than just data; it also includes being able to put together disparate pieces of data to inform relevant decisions. For the air traffic controller, knowing that an aircraft is at a particular altitude, location and heading is level 1 SA; understanding that it is below its assigned altitude and therefore has a deviation is Level 2 SA. The formation of Level 2 SA is highly dependent on the goals and decision requirements of the individual, which may vary significantly, based on the person’s role, within and across teams.

- (3) Level 3 SA—Projection of the current situation to inform likely or possible future situations. Projection forms the third and highest level of SA, and is the hallmark of expertise in SA (Endsley, 1995b, 2018). Situation dynamics forms an important part of SA. By constantly projecting ahead, decision makers are able to act proactively instead of just reactively. For example, the air traffic controller is able to project that two aircraft will collide in the future, based on their current assigned trajectories. Similar to Level 2 SA, there can be considerable variance in Level 3 SA projections based on the differing goals and decision requirements of different team members.

SITUATION AWARENESS IN TEAMS

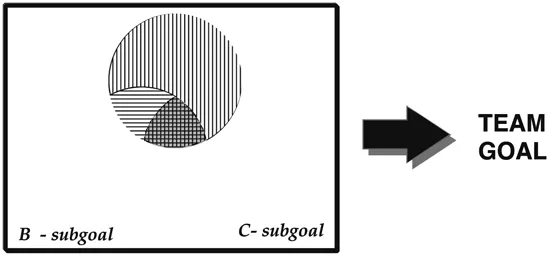

TEAM SA (TSA)

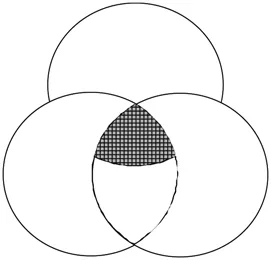

SHARED SA (SSA)

RELEVANCE OF TSA AND SSA

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- Primer (Introduction)

- Chapter 1 Situation Awareness in Teams: Models and Measures

- Chapter 2 Studying Team Cognition in the C3Fire Microworld

- Chapter 3 The Dynamical Systems Approach to Team Cognition: Theory, Models, and Metrics

- Chapter 4 Distributed Cognition in Self-Organizing Teams

- Chapter 5 Unobtrusive Measurement of Team Cognition: A Review and Event-Based Approach to Measurement Design

- Chapter 6 A Method for Rigorously Assessing Causal Mental Models to Support Distributed Team Cognition

- Chapter 7 Quantitative Modeling of Dynamic Human-Agent Cognition

- Chapter 8 Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Modeling Human Factors in Systems

- Chapter 9 Understanding Human-Machine Teaming through Interdependence Analysis

- Chapter 10 Using Conceptual Recurrence Analysis to Decompose Team Conversations

- Index