THE PROMISE OF TOURISM AS A TOOL FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION

This book addresses a critical question facing many aid agencies, academics, governments, tourism organisations and conservation bodies around the world: can tourism work as a tool to overcome poverty? In recent years many proclamations have been made about the actual and potential contributions tourism can make to developing countries, perhaps none more audacious than that of the president of Counterpart International, Lelei LeLaulu, who asserts that tourism represents ‘the largest voluntary transfer of resources from the rich to the poor in history, and for those of us in the development community—tourism is the most potent anti-poverty tool ever’ (eTurboNews 2007—emphasis added).

While most advocates of ‘Pro-Poor Tourism’ (PPT) are more balanced in their assertions, they do agree that tourism can indeed alleviate poverty. This proposition is alluring as we are told tourism is a significant or growing economic sector in most countries with high levels of poverty (Roe et al. 2004). We are also presented with figures on the centrality of tourism to the economies of many developing countries: for example, in 2006 65.9 percent of the Maldives’ export earnings came from tourism, while Vanuatu earned a massive 73.7 percent of its export dollars from this sector (ESCAP 2007: 4). When we hear of village families in Indonesia who earn less than $8 per month in cash and struggle to meet their basic needs, yet they are within close vicinity of a tourist attraction (Schellhorn 2007: 177), it is hard to overlook that tourism might provide them with opportunities to enhance their well-being. 1

However, academic views on the relationship between poverty and tourism have varied widely over the past half century, with the industry being soundly criticised for many years. While in the 1950s tourism was identified as a modernisation strategy that could help newly-independent developing countries to create jobs and earn foreign exchange, in the 1970s and 1980s many social scientists argued that poor people and poorer countries are typically excluded from or disadvantaged by what tourism can offer. During this time tourism was widely critiqued as an industry dominated by large corporations which exploit the labour and resources of developing countries, cause environmental degradation, commodify traditional cultures, entrench inequality and deepen poverty (see e. g. Britton 1982; Pleumarom 1994). Given the strength and vigour of this critique, it is fascinating to see how there has been a concerted push towards a reversal of this thinking coinciding with the development industry’s global focus on poverty alleviation from the 1990s onwards.

Tourism has been identified as a promising economic sector through which to develop poverty alleviation strategies thanks to some persuasive statistics. Developing countries now have a market share of 40 percent of worldwide international tourism arrivals, up from 34 percent in 2000 (UNWTO 2007: 4). For over 50 of the world’s poorest countries tourism is one of the top three contributors to economic development (World Tourism Organization 2000, cited in Sofield 2003: 350). Tourism is also growing rapidly in a number of countries with least developed country status. Tourism accounts for 8.9 percent of employment in the Asian and Pacific region, that is 140 million jobs; in Pacific Island countries, tourism accounts for almost 1 in every 3 formal sector jobs (ESCAP 2007: 4–5). There has been 110 percent growth in arrivals to the least developed countries between 2000 and 2007 compared with an overall increase in worldwide international arrivals of 32 percent for this period (UNWTO, cited in PATA 2008). Furthermore, it is suggested that the approximately $68 billion given in aid annually pales in significance compared with revenues from tourism which are around $153 billion (Ashley and Mitchell 2005, cited in Christie and Sharma 2008: 428).

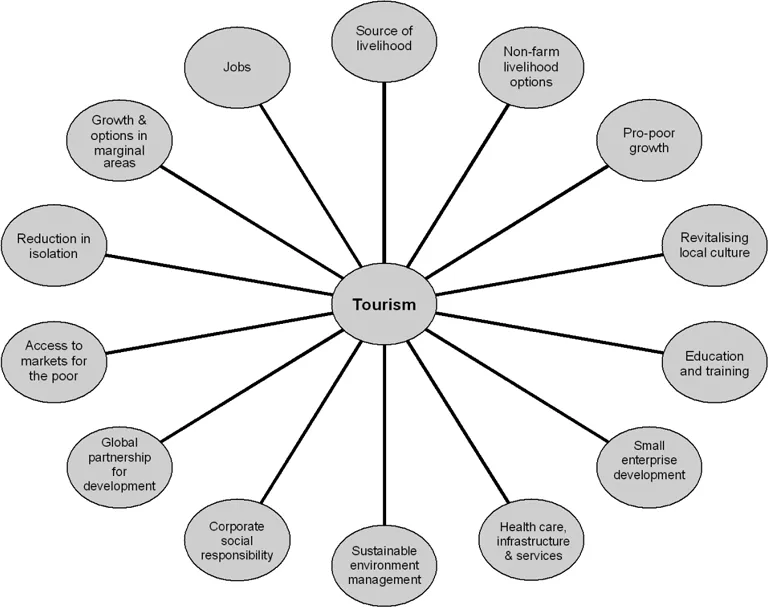

Telfer and Sharpley (2008: 2) claim that ‘the most common justification for the promotion of tourism is its potential contribution to development, particularly in the context of developing countries’. These benefits are summarised in Table 1.1. Firstly, tourism can purportedly bring ‘economic benefits’ which contribute to the well-being of the poor directly through: generation of jobs—the tourism industry in 2009 employed over 235 million people world wide, which accounts for 8.2 percent of all jobs (WTTC 2010: 7); provision of income-earning opportunities for many others who provide goods and services to the industry; and collective community income such as lease money paid by resorts based on communal land or a share of gate takings at a national park going directly to a resident community. By enhancing local livelihood options, tourism can enable some rural communities to thrive rather than undergoing serious decline due to continuous out-migration of their youngest and brightest members (ESCAP 2003: 28; Scheyvens 2007b). Tourism can also bring ‘non-cash livelihood benefits’ to the poor, including conservation of natural and cultural assets, opportunities for the poor to get training and develop further skills, and also indirect benefits through tax revenues which governments use to support infrastructural development such as roading and water supplies, and to provide basic services, including education and health care (Ashley and Roe 2002; Goodwin et al. 1998). Finally, there may be ‘policy, process and participation’ benefits for the poor whereby the government puts in place policy frameworks which encourage more direct participation by the poor in decision-making, where partnerships between the public and private sectors are encouraged, and where communication channels are improved so poorer peoples have better access to information.

There are also strong claims that tourism as a sector has performed better than other sectors in recent years, so that it offers more promise in terms of development strategies. Thus UNCTAD (1998) refers to tourism as the ‘only major sector in international trade in services in which developing countries have consistently had surpluses’. Many countries are being forced to look beyond their traditional agricultural exports (e.g. bananas, cocoa, coffee and sugar) because of the declining value of these products or their diminishing viability due to the demise of traditional trade agreements which had offered preferential access to markets. Comparing the value of export crops with tourism receipts for South Pacific countries over a 20 year period, it has been found that ‘in every case the value of these primary products in real terms has declined and the only sector to demonstrate a continuous upward trend has been tourism’ (Sofield et al. 2004: 25–26).

Even if we put aside exaggerated claims, such as that cited in the opening paragraph of this book that ‘tourism is the most potent anti-poverty tool ever’, the promise of tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation is clearly compelling and the potential benefits extend well beyond the economic sphere (see Figure 1.1). As such it would be negligent to cynically dismiss tourism’s potential here, and this may also do a disservice to the millions of poorer people around the world who, in struggling to enhance their well-being, are looking to tourism as an area of promise.

It is important to consider what these people seek to gain from tourism. As noted by members of the Pro-Poor Tourism Partnership, a small group of academics and researchers who have advocated for PPT, this goes well beyond jobs and business opportunities (Roe et al. 2002). Rather, poor people hope that tourism will achieve many of the following: improve infrastructure in the area, including water, roads and health facilities; make their area safer for all, because tourists do not visit places plagued by crime and insecurity; improve communication facilities, thus giving them greater access to outside ideas and information; enhance community income via lease fees, profit sharing arrangements from joint ventures or donations from tourists; lead to greater pride and optimism due to planning together for tourism, revitalising cultural traditions and welcoming visitors from afar (Roe et al. 2002: 2–3).

However it is also vital that we examine whether unrealistic expectations are being raised, an issue highlighted by the downturn in tourist numbers resulting from the recent global economic recession, and that we seek to

Table 1.1 Pro-Poor Strategies to Provide Economic and Other Benefi ts

understand the agendas of various stakeholders currently endorsing tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation.

THE NEED FOR CAUTION

Over 35 years ago Turner and Ash warned in their landmark book, The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery, that ‘tourism has proved remarkably ineffective as a promoter of equality and as an ally of the oppressed’ (1975: 53, cited in Higgins-Desbiolles 2006: 1193). Is there any reason for us to believe that things have changed radically due to the emergence of the PPT concept?

There could be a danger that, like a number of trends before it (e.g. ‘ecotourism’, PPT is something of a fad, a new way of dressing up the tourism industry to reclaim its credibility not just as an engine of growth but also as a ‘soft’ industry that is both socially beneficial and environmentally benign. Tourism industry players put on ‘green lenses’ in the 1990s, and along with a revival of interest in the environment due to the rising profile of climate change issues, a commitment to poverty reduction seems to have been a key focus for the industry in the first decade of the new millennium.

To date there has been relatively little in-depth critical exploration of the claim that tourism is an effective poverty alleviation strategy. 2 On the contrary, most reports have preached enthusiastically about the potential of PPT to contribute to poverty-reduction in a wide range of countries and contexts. There is some cynicism about PPT however, as seen in the following comment from the Director of the NGO Tourism Concern: ‘The mantra of this international financial community has become “pro-poor tourism”, in the extraordinary fantasy that tourism as it currently operates will lead people, Moses-like, out of poverty’ (Barnett 2008: 1001). The over-enthusiasm for PPT has led others to comment that PPT may be yet another passing trend: ‘… within the tourism industry pro-poor tourism has become the latest in a long line of terms and types to attract attention, funding and energy’ (Mowforth and Munt 2009: 335). As the major players in this industry, as in any industry, are still concerned with profit maximisation, we need to consider whether PPT is just ‘window dressing’, or tokenistic, or, like transformations made under a ‘green agenda’ before it, intended mainly to reduce costs and/or enhance the positive publicity for the agencies concerned. While other writers are more optimistic in their assessment of PPT they tend to conclude that pro-poor tourism ‘… is easier said than done’ (Van der Duim and Caalders 2008: 122).

Thus in the process of exploring the poverty-tourism nexus this book will critically examine a number of questions.

• Firstly, what are the motives of various agencies that have jumped onto the pro-poor tourism bandwagon? Brennan and Allen (2001: 219) contend that ‘Ecotourism is essentially an ideal, promoted by well-fed whites’—could the same be said of PPT, or does this have substance as an approach to development?

• Secondly, moving beyond the hype about Corporate Social Responsibility, can an industry driven by profits ever be expected to prioritise the interests of the poor?

• Thirdly, is a pro-poor approach to tourism likely to impact significantly on the extent and severity of poverty? To date, a number of benefits from pro-poor tourism have been claimed but the changes seem somewhat limited. As Ghimire and Li have noted (2001: 102), tourism has brought economic benefits to rural communities in China, as evidenced by a proliferation of televisions and satellite dishes. However living conditions have not improved on the whole. Ghimire and Li thus question whether poverty can be seen to have been alleviated in this context where there is still a lack of potable water, energy sources are unreliable and sanitation and health care facilities are poor (2001: 102).

• Fourthly, and related to the previous point, can PPT effectively work on a large scale, influencing mainstream tourism initiatives? Even in South Africa, where government agencies have demonstrated a strong commitment to promoting fair trade in tourism, the government is struggling to get the industry to commit to any significant changes (Briedenham 2004).

• Fifthly, can PPT effectively challenge inequitable institutions and structures that are in place, to a greater or lesser extent, in every country? It may, for example, be very difficult for well-intentioned and well-designed PPT initiatives to be implemented effectively if corruption is rife, there is racism and sexual discrimination, and powerful elites are used to capturing the benefits of development interventions.

• Finally, and fundamentally, can PPT help to overcome the inequalities between tourists and local people, when international tourism is to some extent based upon, and highlights, the vast inequalities between the wealthy and the impoverished? This is no more apparent than when viewing tourists’ leisure pursuits: ‘Golf courses and enormous pools are an insult to more than 1.3 billion people denied acces...