![]()

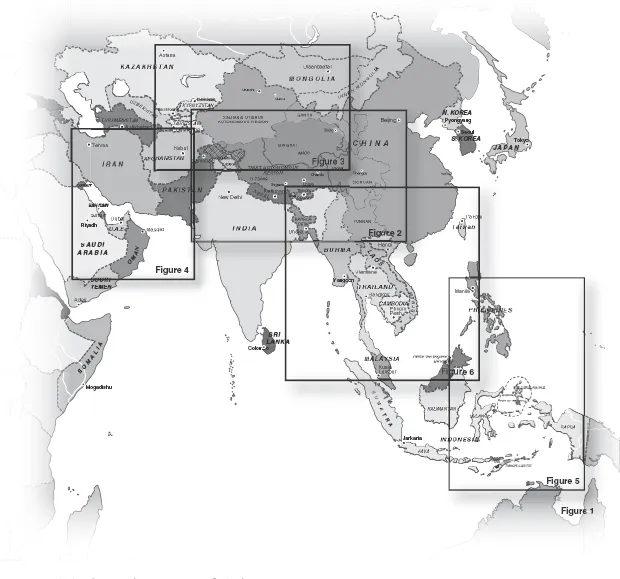

Map 1.1 Overview map of Asia.

Source: Map drawn by Louise Hilmar, Moesgård Museum/University of Aarhus.

1 Varieties of secularism – in

Asia and in theory

Nils Bubandt and Martijn van Beek

Preamble: the haunted airport

In September 2006, shortly before it opened for international flights, the new airport of Bangkok was ritually cleansed by 99 Buddhist monks. The purification ceremony of Suvarnabhumi airport came less than a week after a military coup had abolished the democratic constitution and ousted the Thai Prime Minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, from power, and it responded to persistent claims by workers that the airport, built on reclaimed swamp land and an old cemetery, was haunted by spirits (McGeown 2006). There had been two car accidents on the airport access road that staff blamed on spirit disturbances, and workers reported hearing footsteps and traditional music in the deserted airport terminals at night. The airport, a pet project of Thaksin’s, worth an estimated 3.8 billion dollars, had by this time already run into considerable problems and been delayed for years. It had been dogged by technical difficulties and persistent allegations of corruption and nepotism. Now its management also had to contend with the problem of spirits. Determined to safeguard the public reputation of the airport and boost the morale of its staff, the organisation of Airports of Thailand (AoT) organised a large religious ceremony on 22 September (Mahitthirook 2006). Halfway through the ceremony, proceedings were interrupted when a young luggage operator was possessed by a spirit. Announcing that his name was Poo Ming and that he was the guardian of the land developed for the airport, the spirit went on to demand that a shrine be built to honour the spirits. The monks conferred with the spirit for a while and then sprayed the medium with blessed water after which the spirit left him and the young man regained consciousness.

It seemed some kind of arrangement with the spirits had been achieved. But it was not an altogether stable one. Squadron Leader Pannupong Nualpenyai, who as head of security at Suvarnabhumi airport was in charge of protecting the state-of-the-art facility from criminal activity and terrorist attacks, had himself experienced trouble with the spirits. He had almost crashed his car when a woman in traditional dress walked in front of it before mysteriously disappearing (Parry 2006). While international media treated the ceremony with bemusement, as odd yet fascinating testimony that the Orient would never be truly modern, local officials like Pannupong were more equivocal. ‘Whatever you make of it, it is the belief associated with the Thai way of life. For the non-believer, it is best not to act disrespectfully’, Pannupong Nualpenyai was quoted as saying, and airport management vowed to build a spirit house on the airport grounds (Mahitthirook 2006).

This irruption of the seemingly irrational onto the landing strips of the high-tech airport in several ways challenges conventional ideas about the separation between modernity and tradition, and it serves as a reminder – in Asia by no means uncommon – of the fragility of the division between the ‘secular’ and the ‘religious’. What might instances such as the spirits in Bangkok airport, the simultaneous embarrassment and reality of their presence, tell us about Thai modernity and a Thai formation of the secular? We believe that instances such as these offer a good analytical starting point for a critical analysis of varieties of secularism across Asia. As the airport was taken over by spirits and monks engaged in a struggle for spiritual supremacy, this normally secular space of supermodernity – a locality often regarded as devoid of social history and relations, a quintessential, secular ‘non-space’ (Augé 1995) – became the meeting ground for a variety of seemingly incongruent phenomena: technology and ghosts, airports and religious rituals, global transport and belief. The spiritual occupation and ritual cleansing of an airport to help facilitate the flow of global traffic and secure the future of international tourism in Thailand point to some of the current tensions within Thai modernity, tensions that relate to the coexistence of mediumship and modernity, capitalism and the exchanges with the dead, popular magic and orthodox state Buddhism. The spirits appear awkwardly in the Thai project of modernity aimed at developing the country as a leading Asian tourist destination and a regional economic powerhouse while struggling to combat corruption and strengthen democracy. The spirits are at once embarrassing evidence of ‘popular superstition’ and uncannily real. When the head of security, Pannupong Nualpenyai, who claims to have almost lost his life to spirit intervention, nevertheless expresses a scepticism about spirits when he rationalises the ceremony by appealing to the commonsense of politeness – that it is best to ‘act respectfully’ towards a ‘belief associated with the Thai way of life’, whatever you make of it – he speaks into a reality where spirits are both real and unreal. Their presence induces attempts to domesticate them, both discursively as a matter of ‘Thai belief’ and ritually through the performance of appropriate Buddhist ceremonies. As Charles Taylor suggests, life in a secular age is characterised, amongst other things, by a move from an existence in which belief ‘is unchallenged, indeed unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option amongst others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace’ (Taylor 2007: 3). Whereas Taylor's magisterial work draws up the conditions and problems of a belief in God in Western modernity, it leaves unexplored the challenges posed by the spiritual in modernity outside of the North Atlantic rim. This anthology seeks to begin that task. It does so by suggesting that the kind of secularity described by Taylor is only one amongst others. Taylor describes a secularity characterised by an ‘immanent’ social order in which individuals are ‘buffered’ from spiritual forces by an epistemology that divides an inner ‘psychological’ world from the outer world, and subject from object. The realm of the transcendent can be ‘sloughed off’ by this new ontology and ‘religious’ belief is merely one option amongst others (ibid.: 543).

The haunted airport in Bangkok is therefore an apt place to begin this anthology, because it suggests that secularity comes in other forms as well; forms of secularity, in which spirits are embarrassing and can be rhetorically allocated to the realm of ‘belief’, but in which they cannot easily be sloughed off as a snake sheds its skin. The spirits, rather, impinge on individuals who are not entirely and always buffered from them and they seem to exist in a social order where no easy distinction between political immanence and spiritual transcendence is possible. The haunted airport in Bangkok is for us a place from where one can begin to sketch the outlines of a particular variety of secularism – one of many in Asia. Far from being evidence of a simple ‘re-emergence’ of traditional magic in a modern world, the presence of spirits and monks in the airport (and their subsequent representation in the media) points to a tension within Thai secularism. We suggest that this secularism – like the other varieties of secularism explored in this anthology – is best explored through its rifts, aporias, problems and tensions. The episode at Suvarnabhumi airport and its afterlife in the media is thus made possible and unusual, fascinating and problematic, by a political history that has constructed the public reality of spirits, religion and rationality in a particular way. The problem of ghosts – as they appeared in the airport, in the media and in public practice – speak directly to what Morris (2000a: 471) has called a Thai ‘nationalized discourse of modernity whose oppositional terms are those of science versus magic, rationality versus supernatural belief, the visible versus the invisible, and mind versus body’. Encapsulating – often awkwardly – the oppositions of science versus magic, rationality versus supernatural belief, the visible versus the invisible, is that of ‘secularism’ and ‘religion’. These oppositions have grown out of and are related to a particular kind of discourse about society, public life and the epistemological and institutional organisation of religion and politics. We will use ‘secularism’ as a shorthand for this discourse about how the relationship between ‘religious’ and ‘political’ practices, between subjectivity and public life, between ‘modernity’ and ‘tradition’ are or should be constituted.

‘Secularism’ in this broad sense is common to all the countries that make up the region that we here heuristically call ‘Asia’, well aware that this is not an unproblematic term (Said 1995; Wilson and Dirlik 1994). At the same time, it is also evident that the relationship between what counts as ‘religion’ and ‘politics’, between what goes as ‘modern’ and what is considered ‘tradition’, is characterised by a huge variety. Not only does this relationship vary between different nation-states, the contributions to this volume also demonstrate that competing perceptions of this relationship exist between different historical periods and social groups within the same national space. Despite this difference, we suggest that all varieties of secularism grapple with a similar set of concerns and evince comparable tensions and paradoxes. For us this suggests that a comparative approach to the various formations of secularisms is not only possible but also productive. So while we want to complicate Taylor's picture of a secular age by shifting focus away from the condition of secularism(s) on the North Atlantic rim and explore the shifting conditions of ‘politics’ and ‘the spiritual’ in Asia, we maintain that for all the variety in these conditions, they are all shaped by an institutional, conceptual and pragmatic engagement with ‘the secular’. The spiritual seems to offer a good starting point to explore these secularisms. Let us try to spell out this argument in more detail.

The argument

The anthology suggests that ghosts, spirits and other encounters with the uncanny and the metaphysical erupt as particular problems, or ‘problematizations’ in Michel Foucault's sense, for ‘secularism’ in Asia. For Foucault, ‘problematizations’ are defined as the analytical delimitation of domains of acts, practices or thought that appear to constitute a problem for the way politics is thought and imagined, and by extension also problematic for divisions like that between ‘the secular’ and ‘the religious’ that make particular kinds of politics possible (Foucault and Rabinow 1997: 114). In Foucault's work, madness, crime and sexuality all functioned as ‘problematizations’ – areas of life that came to constitute particularly urgent problems within particular political formations, problems to which an array of solutions were devised. For Foucault, it was by tracing the common root of diversity and urgency of these solutions that a particular diagnostic of politics and power was made possible (ibid.: 117). We will treat the spiritual – as indeed Foucault also seemed to suggest in his later writings (Carrette 2000; Foucault 1988) – as another source of problematisation. The spiritual is here understood as events, practices and concepts associated with the other-worldly that cannot be easily contained within the domains of ‘religion’ or ‘secular politics’. Rather, the spiritual draws into relief the extent to which the notion of a separation between these domains, a key element of secularism, is best understood as a normative project. From within the terms of secularist discourse, the spiritual denotes a site of conceptual unease, at times inviting, even demanding, political comment and action. For us, therefore, the term ‘the spiritual’ comes with no pretensions to cultural essence. Rather, we use it to refer to dimensions of reality that cut across the normative and purified divide between the proper domains of politics and religion within a given formation of secularism. The spiritual, as the contributions to this volume approach it, is a central aspect of the ‘cultural intimacy’ of secularism (Herzfeld 2005).

The spirit episode at Suvarnabhumi airport is an instance of the spiritual as a problematisation in this sense and, hence, a potential source of cultural embarrassment. As a diagnostic event for the current anthology, episodes such as the spirits that haunt the Bangkok airport and the responses they elicit indicate how secularism and religion are discursively, epistemologically and socially constructed as a duality within a particular – in this case Thai modern – context. The event challenges the neat separation between ‘the secular’ and ‘the religious’, resisting unambiguous designations that define it as belonging to one or the other. Although the monks seek to control them through religious ceremony, the spirits are prone to escape; and while the head of security deploys a secularist discourse about ‘Thai belief’ to distance himself from their reality, he also readily admits to have experienced their effect. The spirits are in this sense what Mary Douglas called ‘matter-out-of-place’, a form of categorical mixture that produces cognitive, social, and political discomfort (Douglas 1966: 35). Spirits are a dramatic example of many other instances of what we call ‘the spiritual’ within modern state rationality as well as modern state-sanctioned religion in Thailand. We suggest that the unsuccessful attempt of the media, the monks and the head of security to bring the spirits comfortably into discourse hints at something larger. The spirits become a stone in the shoe of Thai modernity when people's lives – and a national prestige project – are affected by spirits whose reality is a manifestation of ‘traditional beliefs’. This manifestation is particularly embarrassing because it occurs at the hyper-modern airport. And although monks were called in and eventually succeeded in relegating the spirits to their proper place, the meeting of monks and spirits also brought to the fore the historical tension between rationalised Thai Buddhism and the form of popular Buddhism now deemed to be ‘magical’ or ‘fraudulent’ (Kitiarsa 2005; Morris 2000a; White 2005).

Thailand, of course, is not representative of Asia. In other contexts in Asia the distinctions are less strictly policed and a much more overt entanglement of what counts as ‘religion’, ‘politics’ and the ‘spiritual’ is possible. In Tibetan Buddhism for instance the spiritual is overtly threaded through with political authority, and the spiritual is a force that officially secular or even atheist political regimes cannot fully control and certainly cannot afford to ignore (see Barnett, van Beek, and Brox in this volume). Yet also in these examples tensions and ambiguities arise when the relationship between ‘politics’, ‘religion’ and ‘the spiritual’ is restructured and the fissures and aporias within local secularisms become exposed. This brief sketch of the context of a cleansing ceremony at Bangkok airport is therefore not intended to stand for all forms of secularism and their tensions in Asia. But it illustrates the analytical approach of the contributions to this volume. All centre on the ethnographic description of tensions that are produced by events, imaginaries, practices and symbols that do not easily and comfortable ‘fit’ into official, normative secularisms. This lack of ‘fit’ is evidence, we suggest, of shifts in the way secularism is locally defined and practiced. Such cases of tension provide therefore a set of apt ethnographic starting-points from which to explore how modern politics – enframed by an imagined and institutionalised opposition between the secular and the religious – struggles to deal with the uncomfortable irruption into the realm of politics of the spiritual, the esoteric, the ‘supernatural’ and the mystical in contemporary Asia.1

Democracy and the spiritual

Esoteric rhetoric, divination, spirit possession, rumours of sorcery and assertions of magical prowess have always played an important, if often subterranean, role in Asian politics (Chambert-Loir and Reid 2002; Willford and George 2005) – as indeed in other parts of the world. However, in contrast to Africa for instance, where a large number of studies have been devoted to the continued salience of sorcery and magic (Ashforth 2005; Comaroff and Comaroff 1993; Moore and Sanders 2001), much less attention has been given to the significance of the spiritual in Asian democratic politics.2 What we find most striking is that democratic reform has appeared to stimulate rather than curb the entanglement of the spiritual with the political. It would appear that the softening of official secularisms associated with post-authoritarianism throughout Asia has in recent years meant a renewed political salience and public visibility of the spiritual: in Kyrgyzstan, there are widespread rumours that parliamentarians are dependent on the advice of clairvoyants (see Louw, this volume); in China the state officially participates in occult rituals identifying young children as reincarnations of deceased religious figures and rebuilds royal palaces as museums (see Hann, Brox and Barnett, this volume). In post-New Order Indonesia, political parties use diviners in an attempt to ensure their victory in democratic elections (see Bubandt, this volume). In India's Himalayan regions, reincarnate lamas contest elections and are appointed to high office (see van Beek, this volume), the secular roots of the secessionist movement in Kashmir have been all but erased (see Sökefeld, this volume) and the rise of religious nationalism in the final decades of the twentieth century and the recognition of the centrality of religious perspectives and identities for people's lives has give...