![]()

1

The legendary Knossos

Out in the middle of the wine-dark sea there is a land called Crete, a rich and lovely land, washed by the sea on every side; and in it are many peoples and ninety cities. There, one language mingles with another. In it are Achaeans, great-hearted native Cretans, Kydonians and Dorians in three tribes and noble Pelasgians. Among these [ninety Cretan] cities is Knossos, a great city; and there Minos was nine years king, the boon companion of mighty Zeus.

Homer, Odyssey(Book 19)

Any search for the real bronze age Knossos will inevitably be diverted and distracted to some extent by archaic images rising up from the mythic Knossos, the exotic city round which the ancient Greeks wove fantastic legends. Images of Ariadne and Theseus, of Daidalos and King Minos, of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, are hard to shake off. It is best to confront these images at the very beginning and so be aware of the possibility of bias in our thinking, before we look at the archaeological evidence and infer a history from it. It is all the more important to do so since the interpretations of Evans and his contemporaries were strongly influenced by them.

A significant proportion of the Greek myths use Crete as their setting, implying that a Minoan substratum may underlie the cultures of archaic and classical Greece. Some of the myths use the wild scenery of the mountains; others are set in and round an extraordinary building raised at the command of Minos the king, a maze-like palace of unparalleled splendour. Knossos is one of the few places on Crete whose prehistoic name we know. Remarkably, the original denizens of the Labyrinth called it by the same name. Both ‘Knossos' and ‘Labyrinthos' are to be found on clay tablets that were excavated from the ruins of Knossos. The peculiar syllabic script of the Minoan period gives them as kono-so and da-pu-ri-to-jo. Only a handful of Minoan sites have retained their Minoan identity in this way. The clay tablets mention a-mi-ni-so, pa-i-to, tu-riso, ku-do-ni-ja: Amnisos, one of the ports of Knossos, Phaistos, the great ‘palace' centre on the southern side of the island, Tylissos, a farming estate not far to the west of Knossos, and Kydonia or Khania at the western end of Crete.

That the names have survived almost unscathed from a proto-literate era is remarkable. It is even more remarkable that the walls, staircases, drainage systems, frescoes, archives, and treasures of the Knossos Labyrinth have survived well enough for us to be able to reconstruct both the architecture of the building and some of the events that took place there. Girdled by a swathe of cypress and pine trees to shield them from the scouring wind, the pale gold stones of Knossos lie exposed to the sky, revealing to the modern visitor a bewilderingly complicated plan (Figure 31).

The building is roughly square, about 150 metres across, and covers an area of some 20,000 square metres; it consists of the foundations at least of around 300 chambers on the ground floor and, with its original upper floors, may well originally have consisted of a thousand chambers altogether. There were other labyrinths on Crete, notably at Zakro, Mallia, and Phaistos, but this one was easily the largest and the most complicated to be built, the one that was to be remembered in succeeding centuries as the legendary Labyrinth.

The Homeric sagas are thought to have been written down in the eighth century BC after they had been transmitted orally for several centuries. In Book 19 of the Odyssey, Homer tells of Knossos. By 700 BC, it was already a fabulous city, lost in legend,‘...and there Minos was nine years king'. The ‘nine years' is ambiguous. It may mean that Minos ruled for nine years altogether or for nine-year periods; it may mean that Minos was only nine years old, although that seems less likely.

Minos had an extraordinary pedigree. His mother was Europa, the daughter of Agenor, king of the city of Sidon in Phoenicia. One day while collecting wild flowers by the sea shore she rashly climbed onto the back of a particularly fine bull that she saw grazing majestically with her father's herd. It had a silver circle on its brow and horns like a crescent moon. Without warning, the bull, none other than Zeus himself, leapt into the waves and carried her off to Crete. There the bull-god made love to her beneath a plane tree, which was still pointed out as a landmark at Gortyn in the days of Theophrastus, in about 300 BC.

Europa conceived three sons, Minos, Rhadamanthys, and Sarpedon. All three were adopted by Asterios, the king of Crete, who subsequently became Europa's husband. When Asterios died, Minos succeeded him and reigned in accordance with laws given him every nine years by his father Zeus. He divided Crete into three kingdoms, each with its own capital; one he took for himself, another he gave to his brother Rhadamanthys. The third he had intended for this brother Sarpedon, but after a disagreement Sarpedon left Crete for Asia Minor. Minos married Pasiphae, the daughter of Helios and the nymph Crete, and she bore him four sons and four daughters in the palace at Knossos.

Minos was just and wise and yet his reign was not untroubled. When he was claiming Asterios' throne, he boasted that the gods would answer whatever prayer he offered them. He dedicated an altar to the sea-god Poseidon and prayed that a bull might emerge from the waves. Poseidon gave Minos a magnificent white bull, which swam towards the shore and ambled up out of the sea; Poseidon believed that in gratitude Minos would offer it directly back to him in sacrifice, but he did not. Minos kept the bull, a particularly fine specimen, and sacrificed another instead. Poseidon drove the bull mad so that it terrorized the island. According to one version of the myth, it happened that Heracles was on Crete at the time, so Minos summoned the hero to Knossos and appealed to him to do something about the rampaging beast. Heracles agreed, captured it and carried it on his back across the Aegean to Argolis.

Here we can see a reflection of the Minoans' obsession with bulls, an obsession which the Labyrinth's archaeology has proved again and again to be a prehistoric fact. The rhytons, the ceremonial vessels made for pouring libations to the gods, were sometimes designed to look like bulls' heads. Frescoes decorating the Labyrinth walls showed bulls charging and athletes leaping over them or grappling with their horns. Stylized clay and plaster bull horns were used to decorate the cornices and embellish at least two of the Labyrinth's shrines. Many a modern tourist has been photographed against the 1–metre-high Horns of Consecration which now overlook the South Terrace and which probably once stood out of reach on a high cornice. Everywhere at Knossos there are references to the bull. This bull cult was apparently carried across to Argolis, as the myth suggests; at Mycenae a very similar bull's head rhyton to the one at Knossos was found, but with a gold disc on its forehead.

Poseidon was angered by Minos' arrogance and may have resented the Cretan king's unrivalled command of the seas: Minos was credited later with founding the first naval fleet. In another version of the story, Poseidon inspired Minos' wife Pasiphae with a perverted and uncontrollable desire to have sex with the white bull. Pasiphae confided her lust in Daidalos, a gifted Athenian engineer who was living in exile at Knossos. In obedience to his queen, Daidalos built a wooden facsimile of a cow, hollow so that Pasiphae could secrete herself inside it. The cow was then taken to the bull, who promptly mounted it.

From this bizarre union terrible consequences were to spring. Pasiphae gave birth to a hideous monster, a creature that was half-man, half-bull and would feed only on human flesh. It was Asterion, the Minotaur. Minos was horrified and caused Daidalos to build a huge and complex maze to house the monster, the Labyrinth. According to other versions of the myth, Minos consulted an oracle for advice, as a result of which he spent the rest of his life hiding in Daidalos' Labyrinth, out of shame; at its heart he concealed both the Minotaur and its mother, the disgraced Pasiphae.

The upper, mud-brick walls of the Labyrinth must have crumbled away fairly rapidly when it fell into disuse, but the lower walls were made of strong masonry and substantial remains, perhaps two storeys or more high, endured into the post-Minoan period. As the classical city of Knossos grew up adjacent to it, the ruined sprawl of the Labyrinth evoked all kinds of exotic possibilities about the past. The classical Knossians used both the Labyrinth and the Minotaur on their coins: a simple, stylized plan of the building became almost a civic badge, a logo for the classical city. Interestingly, according to Plutarch, the Knossians had their own version of the Labyrinth's story; in it the Labyrinth was no more than an elaborate prison from which no escape was possible. Minos, they said, instituted games in honour of his son Androgeus and the prize for the victors was those youths who were currently imprisoned in the Labyrinth. So one local tradition at least had it that the tribute-children were not put to death in the Labyrinth. They may have suffered any kind of degradation or abuse at the hands of the victors, but they did not die in the Labyrinth. Plutarch mentions Aristotle's view, which was similar: the youths lived on as servants and slaves, sometimes to old age.

But this is to speed ahead of the story. Following his humiliation over the birth of Asterion, Minos was struck by a new misfortune when the Athenians killed one of his sons. Prince Androgeus had gone to Athens to participate in the games. He had won all the prizes and the Athenians had become so incensed by his success that they murdered him. In revenge, Minos mounted a punitive expedition against the mainland, besieging and conquering Megara, Athens' neighbouring city, and then laying siege to Athens itself. The siege dragged on until Minos implored his father Zeus to intervene. Zeus brought a plague down on the Athenians and this finally made their king Aigeus submit. He had to consent to send Minos an annual tribute of seven youths and seven maidens to be fed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. The Athenians had no choice. Year after year, a ship was sent to Crete with a consignment of fourteen tribute-children.

In the darker recesses of Evans' reconstructed Labyrinth it is still possible to feel that it is a place where some rapacious, child-devouring monster might lurk. In shadowy passages like those at the foot of the Grand Staircase in the East Wing, or the narrow claustrophobic corridor leading from the Lobby of the Stone Seat towards the West Pillar Crypt and the West Magazines, it is still possible to imagine that something unpleasant lies in wait. In spite of the large numbers of people and in spite of summer sunshine, it can still seem a haunted place. A correspondent told me of a visit to Knossos some decades ago when he and his party were virtually the only people in the Labyrinth. They reached the empty, featureless rectangle of the Central Court and became aware of a very strong smell of bull, although there was no bull in the vicinity. Evans too found Knossos a haunted place. There is a well-known passage in The Palace of Minos where he describes a solitary visit to the Grand Staircase at night when he was feverish and unable to sleep. Looking down into the dark stairwell he saw the ghosts of Minoan lords and ladies passing elegantly to and fro on the landings below him. At Knossos, mystery, the occult, tragedy and the smell of sacrifice still hang on the air.

Minos' tragic destiny caused him to lose two of his daughters to the gods. He sent his daughter Deione to Libya, where she was seduced by Apollo. She bore him two sons, Amphithemis and Miletus, the latter eventually founding the town named after him, a Minoan colony on the coast of Anatolia. Another of the king's daughters, Akakallis, fell in love with Hermes and bore him a son called Kydon, who later founded Kydonia in the north-west of Crete. She had a daughter by Hermes, Chione, who in her turn was seduced by Hermes; the result of this incestuous union was Autolycus, who inherited from his father the gift of making the objects he touched invisible.

Minos had a son called Glaukos who, as a small boy, went exploring the palace cellars and was curious to see inside the huge storage jars. He climbed up one them and fell in, drowning in the honey it contained. It was some time before the boy's body was discovered and then only thanks to the clairvoyance of the seer Polyeidos. Minos knew that Polyeidos had supernatural powers and ordered him to bring his son back to life, locking him in the cellar until the task was done. After a time Polyeidos saw a snake wriggling across the stone floor and killed it. Then he saw another snake come to the side of the first one, go away and return with a plant in its mouth. It rubbed the body of its dead companion with the herb and immediately revived it. Polyeidos used the same technique on the boy's body and brought him back to life.

New troubles were brewing for Minos in Athens. King Aigeus had a son called Theseus. At least, the king was one of Theseus' fathers: Theseus' mother Aethra shared her affections between Aigeus and Poseidon, and Theseus was conceived as a result of this double union. Like Heracles, Theseus lived an heroic life of combat and challenge. From the beginning his life was filled with dangerous adventures. When he was 16 and in Troizen, his mother told him the secret of his birth and that he was to go to Athens to join his father. After an eventful and dangerous journey, Theseus arrived at his father's court where Medea, Aigeus' new wife, tried to poison him. Feeling the menace of hostility about him the boy drew his sword, which Aigeus at once recognized as his own. Realizing from this that Theseus was his son, Aigeus drove Medea and her offspring from his court, thenceforth sharing his throne with Theseus.

Then came the punitive expedition from Crete and the exaction of a terrible annual sacrifice. The third time the Cretan envoys arrived to collect the tribute, Theseus himself volunteered to go as one of the fourteen victims and Minos agreed that if Theseus should succeed in overcoming the Minotaur with his bare hands the tribute would be forever ended. When the ship arrived in Crete, it was greeted at the quayside by King Minos. Knossos was 5 kilometres inland and served by two ports. One was Katsambas, now a nondescript suburb between Heraklion and its airport; the other was Amnisos, which is now silted up but still recognizable as a harbour, with the submerged foundations of a handful of Minoan houses still visible at the water's edge. The Athenian ship bearing Theseus and the other tribute children may have sailed into either of these harbours.

Stepping ashore, Theseus proudly told Minos that he was the son of the god Poseidon. Thinking this an idle boast, and perhaps remembering his own hubris, Minos threw his gold ring into the harbour and told Theseus that if he was Poseidon's son he would be able to retrieve it for him. Theseus dived into the sea, surfacing again with the ring and also, to the amazement of all, a crown which Amphitrite had given him under the water.

Theseus was nevertheless taken away with the other Athenian youths and maidens to the palace of Knossos where they were led into the Minotaur's Labyrinth. Ariadne, one of the king's daughters, fell in love with Theseus the moment she saw him and resolved to save him somehow from the clutches of the Minotaur. Secretly she gave him a ball of thread which he could unravel as he went into the Labyrinth and use to find his way out again after slaying the monster.

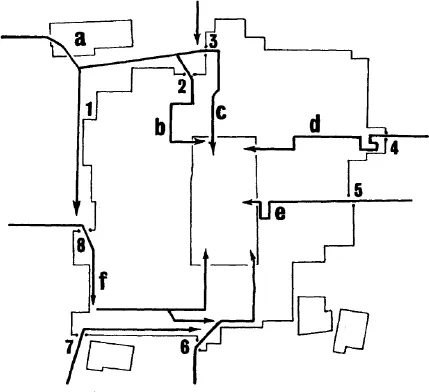

Theseus fastened the thread to the stone door lintel at the entrance to the Labyrinth and unreeled it as he went in. When we look at the ruins on the low Kefala hill today, it is not easy to find the entrance to the Labyrinth even from the outside. It is a pre-classical, inward-looking building with none of the later architectural concerns for symmetry or impressive façades. The edges of the building are severely damaged in some places, so it is not easy to be sure, but it looks as if there were seven or eight entrances, all different in design. From the terminus of the ‘Royal Road' in the Theatral Area, an area possibly set aside for ceremonial greeting, visitors or victims might be led along paved paths to the North Entrance or the West Porch at ground level, or up steps to the North-West Entrance which may have provided direct access to the first floor of the West Wing; Evans never reconstructed the North-West Entrance staircase which he proposed and Graham, writing in the 1960s, does not think that the evidence would sustain it (1969, p. 118). Visitors arriving from the south might enter by the South Porch or, if they came across the bridge over the Vlychia ravine, the Stepped Portico at the building's south-west corner. On the Labyrinth's east front there was a formal entrance by way of an elaborate winding stair, the East Entrance (Evans' ‘East Bastion') (Plate 16), or another staircase 30 metres to the south, although this last may only have connected the palace with a terrace garden area above the revetment walls.

Even when newly built, the entrances may have been difficult to identify, and once the visitor/victim was safely through one of them the way in from there would have been far from obvious. It is worth emphasizing, for reasons that will become clear later in the book, that this is a building conceived within a tradition that was very different from the classical one. To the legend-weavers of the classical age, the Labyrinth was a synonym for ‘puzzle building', a byword for geographical enigma and for barbarously illogical, irrational architecture: it was to become a metaphor for mental confusion. It was, in other words, an ideal setting for an heroic quest, an ideal problem situation for a classical hero of the stature of a Heracles or a Theseus.

Figure 2 The Labyrinth: a plan of the entrances and access routes. a—Theatral Area, b—North-West Entrance Passage, c—North Entrance Passage, d—East Staircase, e—Grand Staircase, f—Procession Corridor. Entrances: 1—North-West Entrance, 2—North-West Portico, 3—North Entrance, 4—East Entrance, 5—Garden Entrance, 6—South Entrance, 7—Stepped Portico

Into the Labyrinth Theseus walked, threading his way along the winding corridors in search of the Minotaur that lurked at the centre, but the centre is even harder to identify than the entrances, even on the excellent modern plans of the building t...