![]()

Part 1

Learning

![]()

Chapter 1

Learning to be a Person in Society

Learning to be me

Originally published as ‘Towards a Theory of Learning’ in K. Illeris (ed.) (2009), Contemporary Theories of Learning, London: Routledge, pp. 21–34. Cross-references refer to the original publication.

Introduction

Many years ago I used to be invited to speak at pre-retirement courses, and one of the exercises that I asked the participants to undertake was that well-known psychological one on identity. I would put on the flip chart the question, ‘Who am I?’ and the response which began ‘I am (a) …’. Then I asked the participants to complete the answer ten times. We took feedback, and on many occasions the respondents placed their occupation high on the list – usually in the top three. I would then ask them a simple question: ‘Who will you be when you retire?’

If I were now to be asked to answer that question, I would respond that ‘I am learning to be me’. But, as we all know, ‘me’ exists in society and so I am forced to ask four further questions:

- What or who is me?

- What is society?

- How does the one interact with the other?

- What do I mean by ‘learning’?

This apparently simple answer to the question actually raises more profound questions than it answers, but these are four of the questions that, if we could answer them, would help us to understand the person. I want to focus on the ‘learning’ for the major part of this chapter, but in the final analysis it is the ‘me’ that becomes just as important. This is also a chapter that raises questions about both ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ and this takes us beyond psychology, sociology and social psychology to philosophy and philosophical anthropology and even to metaphysics.

My interest in learning began in the early 1980s, but my concern with the idea of disjuncture between me and my world goes back a further decade to the time when I began to focus upon those unanswerable questions about human existence that underlie all religions and theologies of the world. It is, therefore, the process of me interacting with my life-world that forms the basis of my current thinking about human learning, but the quest that I began then is one that remains incomplete and will always be so. I do not want to pursue the religious/theological response to disjuncture (the gap between biography and my current experience) here but I do want to claim that all human learning begins with disjuncture – with either an overt question or with a sense of unknowing. I hope that you will forgive me for making this presentation a little personal – but it will also demonstrate how my work began and where I think it is going, and in this way it reflects the opening chapter of my recent book on learning (Jarvis, 2006). In the process of the chapter, I will outline my developing theory and relate it to other theories of learning. The chapter falls into three parts: developing the theory, my present understanding of learning and learning throughout the lifetime.

Developing my Understanding of Human Learning

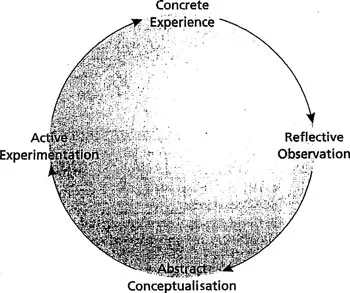

As an adult educator I had a number of experiences in the early 1980s that sparked off my interest in learning, but the one which actually began my research was unintentional. I was invited to speak at an adult education workshop about the relationship between teaching and learning. In those days, that was a most insightful topic to choose since most of the books about teaching rarely mentioned learning and most of the texts about learning rarely mentioned teaching. I decided that the best way for me to tackle the topic was to get the participants to generate their own data, and so at the start of the workshop each participant was asked to write down a learning experience. It was a difficult thing to do – but after 20 or 30 minutes, everybody had a story, and I then asked them to pair up and discuss their learning experiences. We took some feedback at this stage, and I then put the pairs into fours and they continued to discuss, but by this time some of their discussion was not so much about their stories as about learning in general. At this point I introduced them to Kolb’s learning cycle (1984).

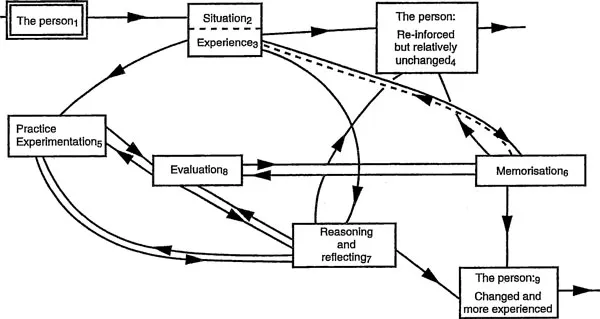

I told the groups that the cycle was not necessarily correct – indeed, I have always maintained that it is too simple to reflect the reality of the complex social process of human learning – and so I asked them to re-draw it to fit their four experiences. We took feedback and produced four totally different diagrams. By good fortune, I had the opportunity over the next year to conduct this workshop in the UK and USA on eight more occasions and, by the third, I realised that I had a research project on adult learning. During all the workshops, I collected all the feedback and, after the second one, I told the participants that I was also using the outcome of their discussions for research. Nobody objected, but rather they started making even more suggestions about my work. By 1986, I had completed the research and wrote it up, and it contained my own model of learning based upon over 200 participants in nine workshops all undertaking this exercise. In 1987, the book Adult Learning in the Social Context (Jarvis, 1987) appeared, in which I offered my own learning cycle.

Figure 1.1 Kolb’s learning cycle.

As a sociologist, I recognised that all the psychological models of learning were flawed, including Kolb’s well-known learning cycle, in as much as they omitted the social and the interaction. Hence my model included these, and the book discussed the social functions of learning itself, as well as many different types of learning. However, it is possible to see the many routes that we can take through the learning process if we look at the following diagram – I actually mentioned 12 in the book. I tried this model out in many different workshops, including two very early on in Denmark, and over the following 15 years I conducted the workshop many times, and in different books variations on this theme occurred.

However, I was always a little concerned about this model, which I regarded as a little over-simple, but far more sophisticated than anything that had gone before. While I was clear in my own mind that learning always started with experience and that experience is always social, I was moving towards a philosophical perspective on human learning, and so an existentialist study was then undertaken – Paradoxes of Learning (Jarvis, 1992). In this, I recognised that, although I had recognised it in the 1987 model, the crucial philosophical issue about learning is that it is the person who learns, although it took me a long time to develop this. What I also recognised was that such concepts as truth and meaning also needed more discussion within learning theory since they are ambiguous and problematic.

Figure 1.2 Jarvis’ 1987 model of learning.

To my mind, the move from experientialism to existentialism has been the most significant in my own thinking about human learning and it occupies a central theme of my current understanding (Jarvis, 2006). It was this recognition that led to another recent book in which Stella Parker and I (Jarvis and Parker, 2005) argued that since learning is human, then every academic discipline that focuses upon the human being has an implicit theory of learning, or at least a contribution to make to our understanding of learning. Fundamentally, it is the person who learns and it is the changed person who is the outcome of the learning, although that changed person may cause several different social outcomes. Consequently, we had chapters from the pure sciences, such as biology and neuroscience, and from the social sciences and from metaphysics and ethics. At the same time, I was involved in writing another book on learning with two other colleagues (Jarvis, Holford and Griffin, 2003) in which we wrote chapters about all the different theories of learning, most of which are still psychological or experiential. What was becoming apparent to me was that we needed a single theory that embraced all the other theories, one that was multi-disciplinary.

Over the years my understanding of learning developed and was changed, but in order to produce such a theory it was necessary to have an operational definition of human learning that reflected that complexity – a point also made by Illeris (2002). Initially, I had defined learning as ‘the transformation of experience into knowledge, skills and attitudes’ (Jarvis, 1987 p. 32) but after a number of metamorphoses I now define it in the following manner:

Human learning is the combination of processes throughout a lifetime whereby the whole person – body (genetic, physical and biological) and mind (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, emotions, beliefs and senses) – experiences social situations, the perceived content of which is then transformed cognitively, emotively or practically (or through any combination) and integrated into the individual person’s biography resulting in a continually changing (or more experienced) person.

What I have recounted here has been a gradual development of my understanding of learning as a result of a number of years of research and the realisation that it is the whole person who learns and that the person learns in a social situation. It must, therefore, involve a number of academic disciplines including sociology, psychology and philosophy. These have all come together recently in my current study of learning (Jarvis, 2006, 2007).

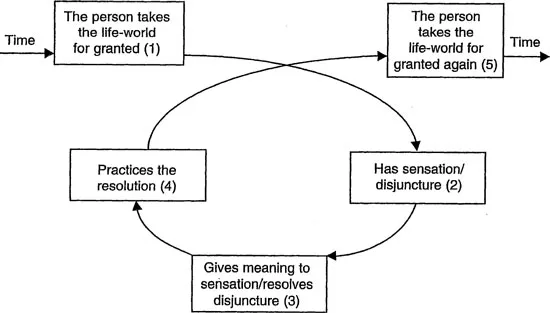

Towards a Comprehensive Theory of Human Learning

As I have thus far argued, learning is both existential and experiential. In a sense, I would want to argue that learning occurs from before birth – for we do learn pre-consciously from experiences that we have in the womb, as a number of different disciplines indicate – and continues to the point when we lose consciousness before death. However, the fact that the individual is social is crucial to our understanding of learning, but so is the fact that the person is both mind and body. All of our experiences of our life-world begin with bodily sensations which occur at the intersection of the person and the life-world. These sensations initially have no meaning for us as this is the beginning of the learning process. Experience begins with disjuncture (the gap between our biography and our perception of our experience) or a sense of not-knowing, but in the first instance experience is a matter of the body receiving sensations, e.g. sound, sight, smell and so on, which appear to have no meaning. Thereafter, we transform these sensations into the language of our brains and minds and learn to make them meaningful to ourselves – this is the first stage in human learning. However, we cannot make this meaning alone; we are social human beings, always in relationship with us, and as we grow, we acquire a social language, so that nearly all the meanings will reflect the society into which we are born. I depict this first process in Figure 1.3.

Significantly, as adults we live a great deal of our lives in situations which we have learned to take for granted (Box 1), that is, we assume that the world as we know it does not change a great deal from one experience to another similar one (Schutz and Luckmann, 1974), although as Bauman (2000) reminds us, our world is changing so rapidly that he can refer to it as ‘liquid’. Over a period of time, however, we actually develop categories and classifications that allow this taken-for-grantedness to occur. Falzon (1998, p. 38) puts this neatly:

Encountering the world … necessarily involves a process of ordering the world in terms of our categories, organising it and classifying it, actively bringing it under control in some way. We always bring some framework to bear on the world in our dealings with it. Without this organisational activity, we would be unable to make any sense of the world at all.

However, the same claim cannot be made for young children – they frequently experience sensations about which they have no meaning or explanation and they have to seek meanings and ask the question that every parent is fearful of: Why? They are in constant disjuncture or, in other words, they start much of their living reflecting Box 2, but as they develop, they gain a perception of the life-world and of the meanings that society gives to their experiences, and so Box 1 becomes more of an everyday occurrence. However, throughout our lives, however old and experienced we are, we still enter novel situations and have sensations that we do not recognise – what is that sound, smell, taste and so on? Both adult and child have to transform the sensation to brain language and eventually to give it meaning. It is in learning the meaning, etc. of the sensation that we incorporate the culture of our life-world into ourselves; this we do in most, if not all, of our learning experiences.

Figure 1.3 The transformation of sensations: learning from primary experience.

Traditionally, however, adult educators have claimed that children learn differently from adults, but the processes of learning from novel situations is the same throughout the whole of life, although children have more new experiences than adults do and this is why there appears to be some difference in the learning processes of children and adults. These are primary experiences and we all have them throughout our lives; we all have new sensations in which we cannot take the world for granted – when we enter a state of disjuncture and immediately we raise questions: What do I do now? What does that mean? What is that smell? What is that sound? and so on. Many of these queries may not be articulated in the form of a question, but there is a sense of unknowing (Box 2). It is this disjuncture that is at the heart of conscious experience – because conscious experience arises when we do not know and when we cannot take our world for granted. Through a variety of ways we give meaning to the sensation and our disjuncture is resolved. An answer (not necessarily a correct one, even if there is one that is correct) to our questions may be given by a significant other in childhood, by a teacher, incidentally in the course of everyday living, through discovery learning or through self-directed learning and so on (Box 3). However, there are times when we just cannot give meaning to primary experiences like this – when we experience beauty, wonder and so on – and it is here that we may begin to locate religious experiences – but time and space forbid us to continue this exploration today (see Jarvis and Hirji, 2006).

When we do get our disjunctures resolved, the answers are social constructs, and so immediately our learning is influenced by the social context within which it occurs. We are encapsulated by our culture. Once we have acquired an answer to our implied question, however, we have to practise or repeat it in order to commit it to memory (Box 4). The more opportunities we have to practise the answer to our initial question, the better we will commit it to memory. Since we do this in our social world, we get feedback, which confirms that we have got a socially acceptable resolution or else we have to start the process again, or be different from those people around us. A socially acceptable answer may be called correct, but here we have to be aware of the problem of language – conformity is not always ‘correctness’. This process of learning to conform is ‘trial and error’ learning – but we can also learn to disagree, and it is in agreeing and disagreeing that aspects of our individuality emerge. However, once we have a socially acceptable resolution and have memorised it, we are also in a position to take our world for granted again (Box 5), provided that the social world has not changed in some other way. Most importantly, however, as we change and others change as they learn, the social world is always changing and so our taken-for-grantedness becomes more suspect (Box 5) since we always experience slightly different situations. The same water does not flow under the same b...