![]()

1 America’s Superhuman Japan

From Rising Sun to globalization rising

“[The Japanese] see billions and billions of their dollars … invested in a country that’s in deep trouble. That’s filled with strange individualistic people who talk constantly. Who confront each other constantly. Who argue all the time. People who aren’t well educated, who don’t know much about the world, who get their information from television. People who don’t work very hard, who tolerate violence and drug use, and don’t seem to object to it.”

Detective John Connor, protagonist of Rising Sun, 1992

In the 1990s, America was “the world’s only superpower.” Japan entered its so-called “lost decade,” and the world seemed to forget America’s brief crisis of confidence and over-the-top preoccupation with Japan.

With any tectonic shift in international relations, educational discourse also is refigured to meet new demands; thus, it matters to reflect on the imagination of the superhuman then and now. “Then” – the trade friction era and its ambience of Cold War-like, zero-sum economic rivalry between the United States and Japan that catapulted the representation of the Japanese worker, student, and parent into a superior position in order to motivate higher levels of productivity among Americans. “Now” – the cluster shock of global terrorism, global economic downturn, rise of population powerhouses of India and China, global warming, and border-crossing diseases – making impossible demands on the ordinary, un-super individuals among us. Popular imagination shoved many of the complexities of globalization into the background immediately after the events of 9/11 and the newly drawn dichotomy of “us”/”them” as Western nations vs. radical Islam. Yet China is also beginning to fill the same space for the “superhuman” that Japan once did in the 1980s.

During the 1980s’ trade friction era, “economic nationalism” frequently described a government using the strong guidance of the state to guide national economic prosperity, whereas economic globalization, with its modus operandi of neoliberalism that became a more frequently discussed topic in the 1990s and 2000s, depicted minimal government intervention in order to maximize profits, especially through overseas markets. This is also true for the management of affect. In economic nationalism, leaders try to generate pride in the educational and material success of the nation, consider cross-cultural contact for utilitarian purposes only, and fear economic as well as ideological challenges to the boundaries of nation. In neoliberalism, power players sometimes speak of free trade separately from nationalist solidarity or patriotic sentiment more neatly accomplished by rallying citizens around dangers that are territorial, cultural, religious, and civilizational. Under neoliberalism, trade functions best when it is free from social interference. This is especially apparent at the global level where democratic processes have not risen to the same level of prestige and power as global economic processes. In 2007, this insulation of policymakers from ordinary citizens was exemplified in construction of a 7.5 mile long, eight foot tall barbed wire fence, costing US$20 million, only to block demonstrators from disturbing the G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany.

In the early 2000s, the fortification of national identity known as neoconservativism occupied a different, morally defined rationality than the ensemble of policies bracketed as neoliberalism, even when those two ideas co-existed in the platforms of many politicians and their supporters. I borrow this point from Wendy Brown, who, in reference to America, demonstrates that an atrophy of democratic culture under neoliberalism was precisely what enabled the mobilization of state authority and the weakening of citizenship responsibility under neoconservatism.1 A similar phenomenon has been present in Japan from the end of the Second World War.

Below I draw attention to the discourses commonly known during the period of US–Japan trade rivalry, with attention to the evolution in America to thinking about Japan as a pure enemy, exemplified in Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun, to American acceptance of Japan as a player in “globalization rising.” Stories that framed the meaning of Japan for Americans, in the hybrid fusions of fiction and non-fiction, not only made the conundrum of “Japan” intelligible; they also compensated for the contradictions of globalization that otherwise would not lend themselves to crowd-pleasing narrative affirmations, such as the superhuman.

Imagining economic nationalism

In nationalism, people imagine unity and forget disunity. Benedict Anderson famously called the nation itself an “imagined community” because “members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” Nations are imagined as sovereign and timeless through strategies that involve remembering and forgetting, acts that encourage people to act as one with fellow members of their nation, even against contradictory evidence that they are not one. Differences of race, ethnicity, class, culture, language, and ideas exist in every nation, but people will forget about them in order to reap the benefits of solidarity, security, and sovereignty, especially if the nation actively promotes its kinship with the state. For Anderson, the “deep, horizontal comradeship” that makes people willing to kill and die, to make “colossal sacrifices,” is confounding, given the historically short-lived, limited idea of nations.2

Economic nationalism typically refers to the mercantile actions of the state, such as the imposition of tariffs and other trade barriers, and it also implies that the collective bond of a nation-state is represented by its key corporations, as well as by its citizens, through their purchasing and productive capacities. But these actions of state, corporation, and “nation” as an imagined community are not always viewed as consistent, simultaneous, or even horizontal, since a nation’s economic success depends on its vertical stratification of workers, and on the ability of its companies and citizens to attract the cheapest labor and goods, irrespective of nationalities. Nor is economic nationalism typically a self-definition; it carries the smirch of anti-freedom, antithetical to Americans who labeled the aggressive expansionism of Japanese business and government leaders’ “economic nationalism” to distinguish such actions from their own presumed economic liberalism (in the classical meaning of practicing free trade). For Americans, it was more difficult to invest in or export to Japan, while the reverse was believed to be true of Japan in America.

But Americans themselves retaliated against Japanese capitalist insularity and expansionism by practicing what was more softly called “pocketbook patriotism,” rallying fellow citizens to buy only American goods and services. Pocketbook patriots drew caricatures of the Japanese economic invasion as being both an omen of the future and a transmigration from the wartime 1940s. Such a populist response constitutes economic nationalism in itself and indeed one that is more literally melded with the “nation” as an imagined oneness of people, rather than the “state” as a legal entity, or the corporation as a potentially transnational business entity. Below I use the term economic nationalism in reference to both America and Japan in their respective political cultures in the 1980s, keeping in mind that the American version often reflected a pervasive mood in the nation that rippled across several layers of popular culture and was consistent with the general American support of patriotism, whereas economic nationalism in Japan generally referred to the policies and practices of its corporations and political shakers.

American populist economic nationalism positioned Japan in a one-way gaze that rendered the spectator as unseen, in control, and less vulnerable than the object under investigation. In visual terms, the object in the lens is not passive but develops the habit of coding himself/herself/itself to meet the expectations of the camera.3 Peter Wollen adds that the spectator does not form some kind of social engagement with the object of the gaze; instead he or she observes a product that has already been subjected to editing for the benefit of an ideal, but detached, “invisible guest.”4

Much of the imagery of Japan in the “Bubble” era or trade war period, whether in visual or print media, fiction or non-fiction, worked with such a “gaze” effect by synthesizing into a singular totality Japan, Inc. as a singular corporate nation-state. Throughout the time of Japan’s economic ascendance, “we” confront (I am considering the construction of America at this point) the scenario of encroachment, invasion, and impending takeover: the “other” is surpassing “us” using smarter, faster, and more efficient workers, machinery, and ideas. But this reaction is not really an inferiority complex as much as the nation-state’s prototypical creation of insecurity, a realm of danger that legitimates the security responses of the state.5 The inferiority ploy works in the same way as appeals to victimization: others did this to us, but with our own superior efforts, we will get even and get better.

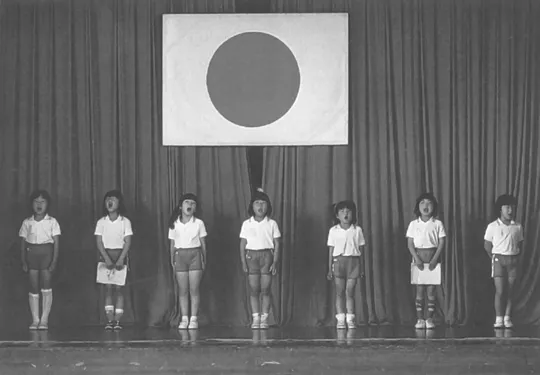

Fortune Magazine’s 1992 cover story titled “Why Japan Will Emerge Stronger”6 juxtaposes two photos, one captioned “It starts here. Strikingly well-disciplined elementary school kids sing Japan’s national anthem …” (ellipsis original). The other continues “… and leads to this. Fujitsu workers test supercomputers at a modern factory outside Tokyo” (ellipsis original, see Figures 1.1a and 1.1b).

Figure 1.1a John J. Curran, “Why Japan Will Emerge Stronger,” Fortune Magazine, May 18, 1992. It starts here: strikingly well-disciplined elementary school kids sing Japan’s national anthem … Picture courtesy of Karen Kasmauski

Figure 1.1b … and leads to this. Fujitsu workers test supercomputers at a modern factory outside Tokyo. Picture courtesy of Alan Levenson

In the former representation, the enthusiastically singing children (all girls) stand attentively onstage beneath a sizeable hinomaru flag, thereby eliciting a gesture of political controversy unknown to Americans, since the legitimacy of the national flag and the national anthem, indeed the idea of wartime-era patriotism itself that the symbols unofficially remind people of, have been hotly contested in Japan since the end of the Second World War. The next image shows a row of young (now, all male) engineers seated in front of high-tech computer screens; they also pivot their serious, bespectacled faces to the camera in mindful choreography. The photo narrative speaks to the American imagination that the traditional, collective, possibly gendered, patriotism of the nation is the key ingredient for economic success, justifying the hopes of many American leaders to inculcate just such a formula. Weaved in with data confirming the continuing economic rise of Japan (despite the signs of slowdown it was experiencing then), the text synthesizes its own totality of state and corporate nation, inspiring Americans to be friendly toward, fearful of, and ultimately more competitive with Japan through their own stars-and-stripes patriotism. This homogenous representation of Japan projects an American fantasy of competitive revenge with national allegiance, gender, knowledge, and power as brewing in the same teapot.

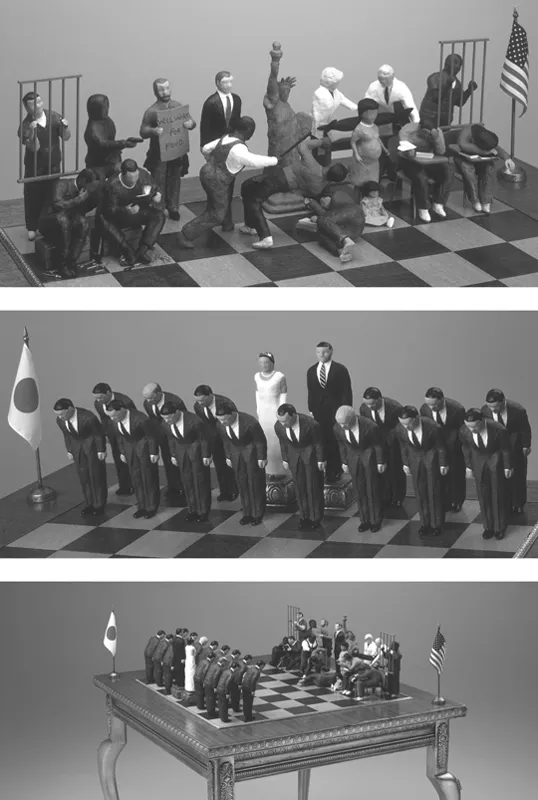

It was as if all the faults of American society were losing to the disciplined and homogenous Japanese, according to sculptor Ed Massey’s artistic summation of the mentality of the era as a chess game of mutual stereotypes (Figure 1.2). Titled in Japanese with the English translation in parentheses, Ōte (Checkmate), Massey’s humorous comment from 1992 on a large, elegantly gilded chess table depicts America’s chess markers as a racially diverse lineup of lazy students, a jobless man, bomb-coddling scientists, incompetent, manual-checking, and altercating workers, a likely single mom, and prisoners.

Figure 1.2 Photograph by Tom Bonner; Ed Massey, “Projects”

Source: http://www.edmassey.com/projects/checkmate.php (homepage); “Nihon wa kabushiki gaisha, Amerika wa tajinshu shakai” (Japan is a corporation, America is a multiracial society), Asahi Shimbun, September 6, 1992.

A homeless woman rests at the base of a shrunken Statue of Liberty while the President (Bush?) stares down the opponents. On the Japan side, only the height-enhanced emperor and empress return the president’s gaze while the rest of the lineup of all male, salaryman-suited males bow in unison. It appears as the beginning of the competition even though America has already lost the game – “checkmate.” Checkmate is “a critical examination of the competition between the world’s two economic giants,” explains the artist.7

In retrospect, compared with almost any other conflict, there are few such critical relics from the era of Superhuman Japan, which I would roughly mark as starting with the beginning of the Reagan administration in 1981 and lasting through the presidential election leading to the inauguration of Bill Clinton in 1993. A movie counterpart to Checkmate might be Ron Howard’s light-hearted dramedy Gung Ho (1986), which conveys the mixed feelings of local and global members of a small town when they invite a Japanese factory to move in to save their economy. Like Checkmate, the initial slinging around of stereotypes in Gung Ho will make the viewer uncomfortable. But the potential clash of cultures turns into a feel-good fest and (opposite of Rising Sun, mentioned below) everyone propitiously learns from the other.

The actual tempest of borderless neoliberalism didn’t begin in the 1980s, of course; one can imagine that in any era the exchange of goods, people, and ideas generates a reaction to prevent limitless exchange from disrupting communities and other aspects of everyday stability and familiarity. The counter-impulses are not just government interventions to “protect” the nation through trade barriers, but the less tangible summoning of imagination to forge a sense of order from disorder. Adam Smith became known as the father of classical economic liberalism for his thesis on the “invisible hand,” postulating that the wealthy of the earth, without either intending or knowing it, bring about a certain distributive equality in the world through their capitalist self-interest. Smith himself is attuned to the imaginative powers necessary to advance this claim, and makes great efforts to attach the “wealth of nations” to agreeable metaphors of social harmony and natural goodness.8 When such “moral sentiments” that naturalize the harmony of self and collective interest become fused into the nation-state, they become part of the modernity that imagines the nation-state as its endpoint in a movement toward a better, enlightened world.

But just as Americans were becoming fearful of the brains and discipline of Asians, theorists from backgrounds in a range of fields in arts and sciences were beginning to sense a climate that did not make as much sense as the harmonious Fortune photo narrative described above. A “postmodern sensitivity” would become necessary to “tolerate the incommensurable,” wrote philosopher Jean-François Lyotard in 1979, defining a “postmodern condition” in which the circulation of knowledge outside the state, and control of commoditized information, would soon become indispensable to power.9 Less encumbered globalization became a seduction and conundrum throughout the world.

Rising Sun

The Vapors’ Dave Fenton discovered...