![]()

1 Boundary, Territory and War

Throughout history, physical terrain, political fiat and conquest have divided the world into independent states and political entities. The result is the man-made and sometimes arbitrary or even imposed boundaries. Until now, there have been over 300 international land boundaries, which stretch over 250,000 km, and separate over 200 independent states and dependencies, areas of special sovereignty, and other miscellaneous entities of the world. At the same time, maritime states have claimed limit lines and have so far established over 100 maritime boundaries and joint development zones to allocate ocean resources and to provide for national security at sea.1

However, not all of these political boundaries have worked well. Some disputed boundaries and cross-border areas may even evolve into the theaters of bloody fights and wars between antagonistic states. Below is just one case of the peril-of-proximity situation.

1.1 Good Boundary, Bad Boundary

On March 26, 2010, a South Korean Pohang-class warship, ROKS Cheonan (PCC-772), exploded and sank in the Yellow Sea (called “West Sea” in both North and South Korea). The incident once again moved the world’s attention toward the troublesome Korean peninsula.

The ship started sinking around 9:30 p.m. local time, after an explosion at the rear end. The 1,500-ton ship carrying more than 100 crew members went down around 9:45 p.m. near Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea. Only 58 crew members were rescued. The incident has been the worst peacetime naval disaster in Korea’s history. The complete picture of the sinking still remains unknown, but South Korea believed that the ship suffered a torpedo attack from North Korea. According to a report released by the Yonhap News Agency (2010), “Seoul’s Navy officials refused to give details, but said a South Korean vessel fired at a ship toward the North later in the evening, indicating a possible torpedo attack from the North. Local residents reported having heard gunfire for about 10 minutes from 11 p.m.”.

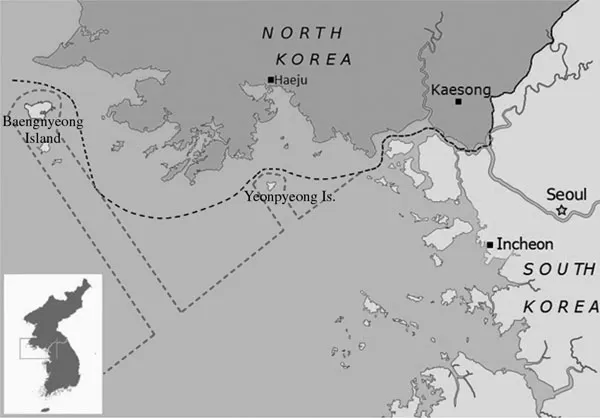

The Northern Limit Line or North Limit Line (NLL) is a disputed maritime demarcation line between North and South Korea in the Yellow Sea. At present, it acts as the de facto maritime boundary between the two Koreas. The line was unilaterally set by the US-led United Nations military forces on August 30, 1953 after the United Nations Command and North Korea failed to reach an agreement. The line extends into the sea from the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) on the Korean peninsula. It continues to run between the mainland portion of Gyeonggi-do (province) of North Korea that had been part of Hwanghae-do (province) of South Korea before 1945, and the adjacent offshore islands, the largest of which is Baengnyeong. When the mainland portion of Gyeonggi-do reverted to North Korean control in 1945, most of the islands still remained a part of South Korea (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The disputed inter-Korean maritime boundaries in the Yellow Sea (copyright © 2010 by Rongxing Guo).

Notes

1 The northern dotted line, set by the US-led UN army in 1953, is the so called Northern Limit Line (NLL).

2 The southern dotted line, or called “maritime military demarcation line,” was set by North Korea in 1999.

Though not claiming all these offshore islands along the NLL, North Korea has never accepted the effectiveness of the NLL, insisting on a border far south of the line that cuts deep into waters currently patrolled by the South Korean navy. In 1977, North Korea attempted to establish a 90 km military boundary zone around the islands controlled by South Korea. In 1999, North Korea claimed a “maritime military demarcation line”, which is located far south of the islands. In addition, North Korea has set up two “security zones” in which South Korean ships are allowed to sail across the disputed area (Figure 1.1). North Korea has proclaimed that it would not guarantee security for any ships coming into waters beyond these two zones. However, South Korea does not recognize this arrangement, insisting that the NLL is the only legal inter-Korean maritime boundary in the Yellow Sea.

Military clashes in the disputed waters of the Yellow Sea have occurred since the 1950s, especially during the crab fishing season – a period during which skirmishes have often resulted in casualties on both sides. Major incidents that have occurred around the NLL since the 1970s are reported as follows:2

On June 5, 1970, a South Korean navy’s “1–2” ship was fired on and sunk by North Korea’s naval vessels in the Yellow Sea, with 20 South Korean soldiers being killed.

In June 1997, a North Korean and a South Korean patrol boat exchanged fire in the Yellow Sea, with no casualties.

On November 20, 1998, a South Korean navy ship fired warning shots at a North Korean warship. On December 18, a North Korean vessel sank near the NLL after being hit by a South Korean navy ship.

From June 9 to 11, 1999, there were three cases of inter-Korean naval conflicts near the NLL. On June 15, North and South Korean warships fought each other, with several North Korean sailors being killed, and a North Korean warship sank and several others were damaged after being hit by artillery shells.

On June 28, 2002, two North Korean navy patrol boats crossed the NLL. As South Korean navy ships approached, the North and South Koreans opened fire. After exchanging fire, both North Korean ships moved back across the NLL. One of the North Korean ships was seen to be heavily damaged and on fire. Six South Korean sailors were killed and 18 wounded during the exchange of fire. It is estimated that the North Korean sailors also suffered more than 30 casualties. A disabled South Korean ship sank while being towed back to shore. On November 16, the South Korean navy fired warning shots at a North Korean patrol boat that crossed a disputed sea border into southern waters. The North Korean boat retreated to North Korean waters without returning fire. A similar incident occurred five days later on November 20.

On November 1, 2004, South Korea’s patrol boats fired on North Korean naval vessels after the latter crossed the disputed maritime boundary (that is, the NLL) in the Yellow Sea. This incident came the same day that South Korea took full responsibility for guarding its side of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).3 The United States withdrew its troops from the border, ending patrols there that dated back to 1953, when the Korean War ended with an armistice.

On May 27, 2009, following a successful nuclear test, North Korea warned that attempts to enforce the NLL would be met with immediate military force. On the same day, naval vessels from the two Koreas exchanged fire in the area of the NLL, reportedly causing serious damage to a North Korean patrol ship and one death. On November 10, South Korean officials reported that a North Korean naval vessel had crossed the NLL and had been fired on by South Korean warships. Authorities on both sides noted that the North Korean vessel had been damaged during the incident. On December 21, North Korea established a “peacetime firing zone” along the NLL, threatening to fire shells into the disputed inter-Korean border waters.

On January 27, 2010, North Korea fired artillery shots into the water near the NLL and South Korean vessels returned fire. The incident took place near the South Korean-controlled Baengnyeong Island. Three days later, North Korea continued to fire artillery shots toward the area. On March 26, the South Korean navy ship ROKS Cheonan (PCC-772), carrying 104 personnel, suffered a torpedo attack and broke into two five minutes after the explosion, with 46 crew members being killed. This incident occurred in waters about one nautical mile (1.9 km) off the southwest coast of Baengnyeong Island, which is located near the NLL. On November 23, North Korea fired about 170 artillery barrages onto Yeonpyeong Island near their disputed border, with four South Koreans (including two marines) being killed and at least 18 people – most of them troops – wounded. This was the first attack targeting South Korean civilians since the Korean War. South Korea immediately responded by firing more than 80 K-9 155 mm self-propelled howitzers, reportedly resulting in casualties in the North. The clash, which came just an hour after Pyongyang warned the South to halt the naval exercises that were jointly conducted by the US and South Korea near the NLL, almost brought the Korean peninsula to the brink of war in the following month.

The long-lasting navy clashes near the NNL have potentially set up a dangerous diplomatic situation in Northeast Asia and beyond. In order to secure a long, sustainable peace accord between North and South Korea, policymakers need to pay attention to the inter-Korean maritime boundary in the Yellow Sea (see Figure 1.1). Unlike the Korean DMZ, which is officially included in the Armistice Agreement of 1953 between the United Nations and North Korea and China, the NLL is not recognized by North Korea. Even worse, there are neither natural nor artificial barriers on either side of the NLL. Given the highly tensed relations between North and South Korea, nobody can predict that the past bloody naval clashes in the Yellow Sea will not happen again someday in the future.

Indeed, the Korean NLL is not a good international boundary. Then, are there any ways of avoiding the navy catastrophe in the Yellow Sea as well as other cross-border conflicts in the rest of the world?4 To answer this question, we need to secure more knowledge relating to boundary demarcation and cross-border territorial management.

1.2 Fuzzy Boundaries and Uncertain Territories

In most cases it is difficult to say what constitutes a good international boundary. However, it is essential that in diplomatic notes, treaties and other documents, the ambiguity in verbal description of international boundaries should be avoided. Usually, cases of discord of a serious nature have been caused by slight and unintentional ambiguities in the description of boundaries in formal documents. These flaws may be due to unfamiliarity with the peculiarities of the geographical features, human or natural, along which the boundary extends, or to lack of knowledge of the pitfalls in boundary description.

Boundary and territorial disputes are politically sensitive issues, especially when one or more countries or groups of people concerned adopt a confrontational strategy. If governments or people have a stake in a disputed area then they are very sensitive about how this area is portrayed in maps. Documents on boundary description may be used by diplomats, lawyers, surveyors, cartographers and field engineers. Therefore, the text should be as free as possible of terms peculiar to one profession.

There are various methods (or techniques) that neighboring states can use to describe their political boundaries. And, in practice, more than one of them may be employed on different sectors of a single boundary. Technically, most of the existing international boundaries of the world have been defined:

- by turning points or angles. This method requires detailed surveys and sufficiently accurate field data for the choice of major turning points or angles. The points or angles may be described by latitude and longitude or other coordinates, by bearings to landmarks, or in other precise terms.

- by courses and distances. This method may be suitable for boundaries in water bodies. It is sometimes combined with description by turning points. If this is done, one method should be stated to rule in case of contradiction. The turning point method is superior in that an error affects only two segments. An error in a course of distance affects all subsequent locations.

- by natural features. International boundaries may be described as following certain natural barriers or screens (including mountains, rivers, lakes, seas and other water bodies). It should be noted that, without clear definitions and/or bilateral (and, if necessary, multilateral) agreements concerning the boundaries between barriers or screens, disputes might arise.

- by human features. This method may be suitable for boundaries that are determined primarily by ethnic, linguistic or religious identities. It should be remembered that sometimes the demarcation commission will feel constrained to fix the boundaries since some human features are too fuzzy to be identified.

Indeed, inappropriate actions in boundary demarcation have usually led to boundary and territorial disputes. The following common errors and intricacies in boundary description are of particular noteworthy: (1) inappropriate topographical terms and place names; (2) vague geographical and geometrical features; (3) intricate human and cultural features; and (4) inconsistent or contradictory statements.

1.2.1 Inappropriate Topographical Terms and Place Names

Most topographic terms (such as “crest”, “range”, “chain” and “foothills” of mountains, and “source”, “end”, “mouth”, “middle” and “bank” of rivers) are vague; sometimes they may have varied locations due to geological or hydrological changes. In an ideal boundary demarcation document the topographical terms used as boundaries should be specifically defined with detailed and, if possible, quantitative information. In addition, most existing names used for places have a long history; and they usually refer to areas rather than geographic coordinates. They are therefore not able to precisely define political boundaries.

If a mountain exists between adjacent political regimes it usually serves as a political boundary. Mountains, when serving as military borders, have the advantage of being easy to defend but difficult to attack. However, precipitous mountains, as political and administrative boundaries, do have the disadvantage of making it difficult for the relevant countries or regions to develop cross-border trade and economic cooperation. Detailed description of mountain boundaries is needed. In general, a water parting (watershed in UK usage) is by no means always a barrier, or along a line of hills or mountains, or even visible. Its chief virtues as a political boundary are that it is precise, and that it separates drainage basins, which for many purposes are best treated as units under a single government. Some peculiarities of water partings (Jones, 1943, p. 105) are:

- They often lie well away from the zone of high peaks.

- Along the water parting may be lakes and swamps with outlets in both directions.

- There may be streams and even large rivers which split and drain in two directions.

- The water parting may be extremely crooked.

- Underground drainage may prevent ready determination of the water parting.

- Basins without drainage to the sea (due to evaporation) may bifurcate the water ...