- 492 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tribe and State in Iran and Afghanistan (RLE Iran D)

About this book

In 1978 and 1979 revolutions in Afghanistan and Iran marked a shift in the balance of power in South West Asia and the world. Then, as now, the world is once more aware that tribalism is no anachronism in a struggle for political and cultural self-determination. This books provides historical and anthropological perspectives necessary to the eventual understanding of the events surrounding the revolutions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tribe and State in Iran and Afghanistan (RLE Iran D) by Richard Tapper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

The Scope of the Volume

The notion of ‘tribe’ is notoriously vague. For some, ‘tribes’ are what anthropologists study, for others a ‘tribe’ is a very specific form of economic and political group. In fact the term has been used in such a variety of ways in social anthropology, as in other fields, that, as with ‘race’ in physical anthropology, it has almost ceased to be of analytical or comparative value. The issues are conceptual, terminological, and to some extent methodological. Can we talk of ‘tribal society’ as a particular stage of social evolution? Is ‘tribal culture’ an identifiable complex? Are ‘tribes’ groups with particular features and functions? Are they found at particular levels in a political structure? How far can ‘tribes’ or ‘tribal groups’ be analysed in isolation from wider political, economic and cultural contexts? Are ‘tribes’ the creation of states? Is it useful to contrast ’tribal’ with ‘peasant’ society? Or ‘tribalism’ with ‘feudalism’, or with ‘ethnicity’? Or ‘tribe’ with ‘clan’ or ‘lineage’ or ‘state’? Is ‘tribe’ merely a state of mind?1

Such questions are not merely academic. They are live political issues in many countries of the world, and in many cases, ignoring or sometimes deliberately exploiting the ambiguities of the notion of ‘tribe’, states adopt unfortunate and often disastrous policies towards their ‘tribal’ populations.

The following chapters tackle some of these questions as they affect two particular states, Iran and Afghanistan, in whose provincial and national history up to the present day ‘tribes’ and ‘tribalism’ have always played a prominent part. The relation of tribe and state emerges as two clearly distinct but closely linked issues: the first is the relation of specific tribal groups with specific states as empirical political forces; the second is more general, and shades into the classic oppositions in the history of social philosophy, such as community and society, kinship and territory, status and contract.

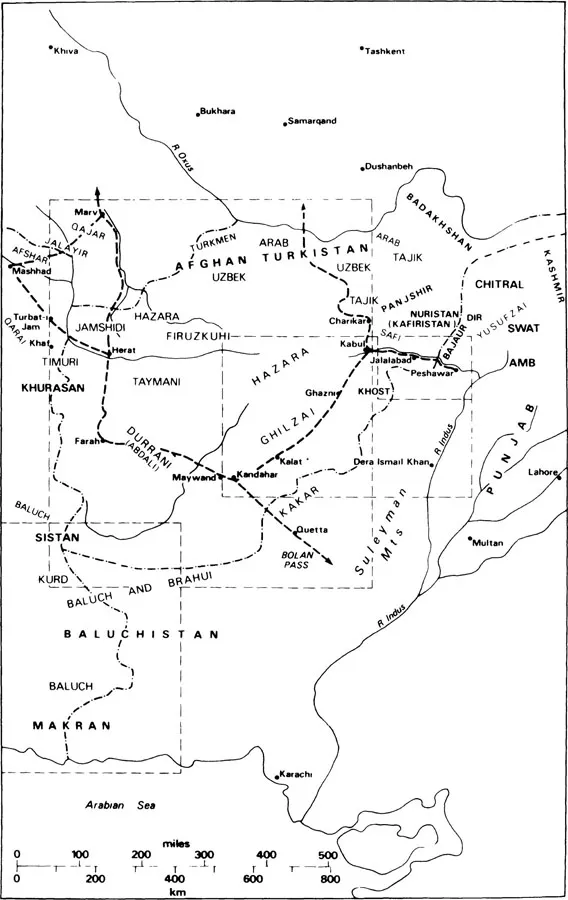

MAP 1: Sketch-map of Iran and Afghanistan, to show places mentioned in chapter 1, with approximate tribal locations_in the nineteenth century

Tribal groups in Iran and Afghanistan are conventionally viewed as historically inveterate opponents of the state. They were notorious as makers and breakers of dynasties, while both countries were ruled by dynasties of tribal origins until the twentieth century. Some years ago, Lambton observed of Iran,

Control of the tribal element has been and is one of the perennial problems of government … All except the strongest governments have delegated responsibility in the tribal areas to the tribal chiefs. One aspect of Persian history is that of a struggle between the tribal element and the non-tribal element, a struggle which has continued in a modified form down to the present day. Various Persian dynasties have come to power on tribal support. In almost all cases the tribes have proved an unstable basis on which to build the future of the country.2

These remarks apply, though in very different ways, to both Afghanistan and Iran, and in different ways to the various tribal groups within each. They apply of course to much of the Middle East, where ‘tribes’ have never, in historical times, been isolated groups of ‘primitives’, remote from contact with states or their agents, but rather tribes and states have created and maintained each other as a single system, though one of inherent instability. The reason for a comparative focus here on Iran and Afghanistan is not merely that these two countries are currently undergoing radical upheaval – nor that the editor happens to have made a study of tribal groups in both – but that historical and cultural links between them and between their tribal groups are broader and deeper than between either country and any other of their neighbours. This is not to deny the importance of links between tribal and ethnic groups across the frontiers of Iran with Turkey, Iraq, the Soviet Union and Pakistan, or of Afghanistan with the Soviet Union, Pakistan and even China, which are referred to in several chapters.

Nor is the historical period 1800–1980 chosen arbitrarily. By 1800, the Durranis and the Qajars, the last major tribal dynasties to rule each country, were in power, though shifts between the Sadozai and Barakzai branches of the Durranis were still to take place. Both dynasties survived until the twentieth century, at once because of and in spite of the Great Power rivalries which led to the end of independence and the apparent decline of tribalism in each country. The renewed, albeit changed importance of tribalism in the early 1980s needs no further comment at this stage. To have extended the historical baseline for the book back into the eighteenth century would have called for consideration of the rise of the Durranis and Qajars to power, and of their transformation from tribal chiefdoms into ruling dynasties. Although avoiding such important problems, subject perhaps for another book but beyond the scope of this one, several chapters do consider to what extent and in what senses the organisation and structure of the state in nineteenth century Afghanistan or Iran were permeated by the ‘tribalism’ of the ruling group.

The social, ecological, economic and other bases of the ‘tribal problem’ are considered in depth in this book, as is the role of the tribes and their leaders as actors and agents in the Great Game of Asia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But if the states involved were preoccupied by a ‘tribal problem’, the tribes could be said to have had a perennial ‘state problem’; none was ever, at least during recent centuries, totally unaffected by any state. Another major theme of this book is an assessment of this ‘state problem’, that is the role of states in creating, transforming, or destroying tribal institutions and structures.

In considering the degree to which the differential impact of states and their policies can explain the variety of economic, social, and political forms evident among the tribes of Iran and Afghanistan, contributors to this book insist on the necessity for a multi-causal explanation. Several chapters, accepting that there can be no example of a ‘pure’ tribal society in these countries, seek to elicit the essence of ‘tribe’ by distinguishing ‘internal’ and ‘external’ factors impinging on tribal society. This has led many contributors to the second, wider view of ‘tribe-state’ relations, not as an opposition of substantive social, economic and political structures so much as an opposition of tendencies, modes or models of organisation, not just analytically distinct but consciously experienced as a tension within the tribal groups discussed. It is at this level that tribal forms and tribe-state relations in Iran and Afghanistan seem to be most fruitfully comparable with other parts of the world.

Any comparative study must begin, however, with an attempt at definition, typology and classification, if only to establish what is being compared; only then can the comparison produce explanation of variation and generalisation. We begin here with an inability to produce a substantive definition of our subject – ‘tribe’ – which in Iran and Afghanistan specifies little about system of production, scale, culture or political structure. Historically, in these countries, groups defined by a wide range of different criteria have been called ‘tribes’. Moreover, tribal groups commonly comprise several levels of organisation, from camp to confederation. Again, different criteria define membership of groups at each level, and it is not agreed at which level the term ‘tribe’ is appropriate. Definition is not aided by indigenous terminology, which includes a variety of words of Turco-Mongol and Arabic origins, often used interchangeably and without precision in the literature.3

Different writers – historians, anthropologists, political agents, travellers; Europeans, Russians, Iranians, Afghans – have, according to their previous experiences, their personalities and their objectives, constructed, maintained and only occasionally confronted widely varying images of the tribes they encountered in Afghanistan and Iran.4 The general view of tribal society among contemporary writers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries opposed it to settled urban society, the civilised Islamic ideal. While the city was the source of government, order and productivity, the tribes had a natural tendency to rebellion, rapine and destruction, a tendency which might be related to the starkness of their habitat and its remoteness from the sources of civilisation, and also to the under-employment inherent in their way of life. Such a view has some justification, but it is superficial and over-simplified.

Beyond this, conventional images of tribes in the two countries differ. Afghan tribes are renowned as hardy, independent, warlike mountaineers, farming barren fields and rigorous if not fanatical in their devotion to Islam. The tribes of Iran by contrast are supposedly pastoral nomads, organised into strong centralised confederacies under powerful and aristocratic chiefs, and notorious for their ignorance of and indifference to Islam. There is some truth in these stereotypes too, at least as a basis for drawing a contrast between tribes in the two countries, but they are nevertheless exaggerated, and exceptions abound in each case.

A better understanding of the nature of tribal political organisations, and of relations between tribal and non-tribal society, must be sought in a closer historical examination of the social and economic basis of the tribal system. Unfortunately, research on this topic has hardly begun. The sources for it are mostly written from a distance by outsiders viewing the tribes with hostility or some other bias. They mostly concern matters such as taxation, military contingents, disturbances and measures taken to quell them, and inaccurate lists of major tribal groups, numbers and leaders. They rarely deal specifically or in reliable detail with the basic social and economic organisation of tribal communities, and mention individual tribes only when prominent in supporting or opposing the government, when involved in inter-tribal disorders, or when transported from one region to another. We still have only the vaguest notions of tribal economies in nineteenth and early twentieth century Afghanistan and Iran: what the relations or production were and how they have changed; who controlled land and how access was acquired; what proportion of producers controlled their own production, how many were tenants or dependants of wealthier tribesmen or of city-based merchants, and whether control of production was exercised directly or through taxation or price-fixing. The sparse information in the sources must be supplemented and interpreted by tentative and possibly misleading extrapolations from more recent ethnographic sources.

Some of the dangers are evident in the recent interesting exchange in Iranian Studies between the historians Helfgott and Reid. Helfgott, whose main study has been of the rise of the Qajars, argues that the Iranian state was composed of two or more separate but linked ‘socio–economic formations’. Apparently extrapolating from the Basiri (Basseri) of the modern era, he characterises Iranian tribes as pastoral nomadic kinship-based chiefdoms that form closed economic systems; such nomadic socio-economic formations are distinct from but in constant relation with the settled agricultural and urban formations. Unfortunately he produces little evidence for his argument, overstresses the role of pastoral nomadism, kinship and chiefship in Iranian tribal society, and underestimates the will and capacity of Iranian pastoral nomads to produce surplus. He is accused of theoreticism by Reid, whose own version of tribal organisation, to which he is led mainly by data on administration and the perspective of the state, is that its essence in Iran was the highly complex centralised oymag system that flourished under the Safavids; oymaqs were neither simply pastoral nor based on kinship (though their sub-divisions may have been); they were ‘states’, but they were also ‘tribes’, says Reid, because their leadership was hereditary. Such groups, however, could not be called ‘tribes’ according to accepted criteria, but were rather ‘confederacies’, and they are not comparable with the nomadic tribal groups to which Helfgott is directing his argument; while on Reid’s own admission the oymaq system disintegrated by the eighteenth century and hence was of no direct relevance to tribalism or pastoral nomadism in the period since.5

One fallacy that needs early correction is that tribes are essentially, if not generally, pastoral nomads. Numerous observers have noted how the geography and ecology of both countries favours pastoral nomadism. The terrain and climate make much of the land uncultivable under pre-industrial conditions, and suitable only for seasonal grazing; and as only a small proportion of such pastures can be used by village-based livestock, vast ranges of steppe and mountain are left to be exploited by nomads -mobile tent-dwellers. Such nomads until very recently numbered two to three millions in each country, and almost all were tribally organised. The difference was that, although most tribespeople in Iran were nomads, in Afghanistan most tribespeople were settled cultivators who had little or no leaning to pastoralism or nomadism.6 in other words, as has been argued by Barth and others, tribalism is more necessary to nomadism than nomadism to tribalism.

Another area of misconception is that of tribal political structures. The allegiance of tribes-people to a set of comparable political groups and leaders is often assumed, especially in the literature on Iran. But this assumption is the product of a state viewpoint, according to which even the most autonomous inhabitants of the territory over which sovereignty is claimed should have representatives and identifiable patterns of organisation. The sources tend to record these as ‘chiefs’ and ‘tribes’, whereas such entities may not exist except on paper. We are left wondering, for example, who the Bakhtiari are: are they followers of the Bakhtiari khans? or merely the khans themselves? or the inhabitants of the territory known as Bakhtiari? Are all those described as Bakhtiari conscious of cultural or political unity? Tribal names found in the sources – and used in the narrative below – imply a uniformity of structure which (if it exists) may be entirely due to administrative action, and may disguise fundamental disparities of culture and society.

If such problems are appreciated, it will clearly be impossible to attempt a precise terminology that will not misrepresent the varied nature of the tribal societies under consideration. But it may be helpful to suggest some distinctions to bear in mind, to be applied less to groups and individuals than to the kinds of processes that affect them.

Tribe may be used loosely of a localised group in which kinship is the dominant idiom of organisation, and whose members consider themselves culturally distinct (in terms of customs, dialect or language, and origins); tribes are usually politically unified, though not necessarily under a central leader, both features being commonly attributable to interaction with states. Such tribes also form parts of larger, usually regional, political structures of tribes of similar kinds; they do not usually relate directly with the state, but only through these intermediate structures.7 The more explicit term confederacy or confederation should be used for a local group of tribes that is heterogeneous in terms of culture, presumed origins and perhaps class composition, yet is politically unified, usually under a central authority: examples include the Khamseh and Qashqai (chapter 9), the Shahsevan (chapter 14) and many Kurdish groups such as the Shakak (chapter 13). It is useful further to distinguish confederacies, as groups of tribes united primarily in relation to the state or extra-local forces, from coalitions or clusters of tribes, more ephemeral unions for the pursuit of specific local rivalries, perhaps within a confederacy and probably without central leadership.

It is better not to use the term ‘tribe’ for major ethnic groups or nations, such as Afghans, Pushtuns/Pathans, Kurds, Hazaras, Turkmens, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Lurs, Arabs, Baluches, which are culturally or linguistically distinct but not normally politically unified – though political and territorial units bearing these names have existed in each case.8 A problem arises with some major subdivisions of these ethnic groups, that are culturally and politically distinct and hence constitute ‘tribes’, yet their own subdivisions, at perh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Abbreviations used in Notes

- Preface

- A Note on Transliteration and Usage

- The Contributors

- 1. Introduction

- 2. State, Tribe and Empire in Afghan Inter-Polity Relations

- 3. Khan and Khel: Dialectics of Pakhtun Tribalism

- 4. Tribes and States in the Khyber, 1838-42

- 5. Tribes and States in Waziristan

- 6. Political Organisation of Pashtun Nomads and the State

- 7. ABD Al-Rahman’s North-West Frontier: The Pashtun Colonisation of Afghan Turkistan

- 8. Why Tribes Have Chiefs: A Case from Baluchistan

- 9. Iran and the Qashqai Tribal Confederacy

- 10. Tribes, Confederation and the State: An Historical Overview of the Bakhtiari and Iran

- 11. On the Bakhtiari: Comments on Tribes, Confederation and the State

- 12. The Enemy Within: Limitations on Leadership in the Bakhtiari

- 13. Kurdish Tribes and the State of Iran: The Case of Simko’s Revolt

- 14. Nomads and Commissars in the Mughan Steppe: The Shahsevan Tribes in the Great Game

- 15. The Tribal Society and its Enemies

- 16. Tribe and State: Some Concluding Remarks

- Index