![]()

1 Growth and transformation during two centuries

Sweden’s road from the late eighteenth century to today’s post-industrial, service-based society may appear to be long. Back then, agriculture was the mainstay of the economy. People lived in villages where land was jointly owned, and the household was the basic economic unit. The cycles that govern human existence were shorter in many respects – life expectancy was half of what it is today, and nearly all of what was produced (most of which was food) was consumed within a year. The harvests varied from one year to the next, and earning a livelihood was an uncertain proposition. But human cycles were longer in another sense. Social change was so slow as to be indiscernible. Social structures appeared to be immutable, stable and static. While people realised that their personal circumstances would change over the course of their lifetimes, they expected fundamental transformation only in the afterlife. These days, mobility and transformation – whether in the form of opportunities or threats – are part of daily life as well.

But the seeds of accelerating change had already been planted in the late eighteenth century. The enclosure movement, which was to transform the organisation of agriculture and pave the way for it to be market-oriented, had begun. The growth of the lower classes that had been spawned by the agrarian economy portended the breakup of centuries-old class-based society. Cottage industries were expanding in the rural areas, and new laws were being passed that set the stage for greater mobility and exchange of goods, as well as for a reallocation of resources.

All of these changes were dynamic. They pointed forward, interacted with each other and merged in a cumulative process of growth and transformation whose consequences were yet unforeseeable.

Many parts of the late eighteenth-century world experienced changes that were greater and more radical than those in Sweden. Three revolutions altered the course of history. The British colonies of North America revolted and formed the United States in 1776. Europe was shaken by the French Revolution of the 1780s and the wars of subsequent decades that remoulded nations according to new principles. Meanwhile, the pace of the British Industrial Revolution accelerated. The use of coal, steam power and machinery was about to create the first industrial society. The foundation was laid for industrialisation and growth in an expanded world economy.

These mega-trends suggest similarities as well as differences with the times we live in. The late twentieth century brought a major upheaval that is variously referred to as the emergence of the service economy, the Third Industrial (electronic) Revolution and the dawn of the information age. Europe underwent a political realignment, and industrialisation spread to East and Southeast Asia, which has become an increasingly independent and dynamic engine of the global economy. The world has again entered a phase of rapid transformation.

This book examines the evolution of the Swedish economy over the past two centuries. Focusing on growth and transformation, it strives to provide a long-term perspective on the historical contexts and forces that have shaped twenty-first-century Sweden.

Growth and transformation

Growth has been one of the most distinctive economic trends in Sweden during the past 200 years. Although the population has almost quadrupled, inflation-adjusted per capita output and income have risen continuously. Sweden is among the countries that have enjoyed the most rapid growth. Per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has averaged almost 2 per cent annual increases since 1800.

But in response to fluctuating conditions, the rate of growth has varied considerably. After fairly slow growth in the first half of the nineteenth century, the rate accelerated until 1975 in the wake of industrialisation. Sweden became one of the richest nations in the world. Growth has slowed down relative to both previous phases and the rest of the world since the mid-1970s (Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 GDP per capita in Sweden, 1800–2005. Fixed (1995) prices, Kronor.

Source: see Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Annual GDP growth per capita, 1800–2005. Fixed prices

Sources: Johansson (1967), Krantz (1986, 1987a, 1987b, 1991), Pettersson (1987), Schön (1988, 1995). Statistical Communications, National Accounts; Historical Statistics, Part 1.

While average annual growth of just under 2 per cent may not sound so remarkable, it adds up to an enormous change over the course of 200 years. That process can be illustrated in different ways. Imagine that industrialisation had never occurred and that annual per capita GDP growth had remained at the 0.4 per cent level of the early nineteenth century. In that case, personal incomes would be less than one tenth of what they are now and Sweden would compare unfavourably with most developing countries.

On the basis of the above GDP figures, the average Swede now consumes more than 20 times the volume of goods and services as at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In other words, less than three weeks would suffice to produce what took an entire year back then. Perhaps more impressive is that a twenty-first-century Swede can consume as much in that short period of time as his or her historical counterpart could in a year. But long-term growth is not simply a matter of numbers. Nobody is physically capable of consuming so much in a matter of weeks. Production and consumption have changed qualitatively as well as quantitatively.

Social transformation has many faces. Growth has spurred radical change in virtually every area of life. New technologies and products have been introduced; factories, companies and entire sectors have arisen; transport and communication have been revolutionised; the nature of work has been transformed; education serves a different function; living conditions and lifestyles have evolved; laws and regulations have been recast.

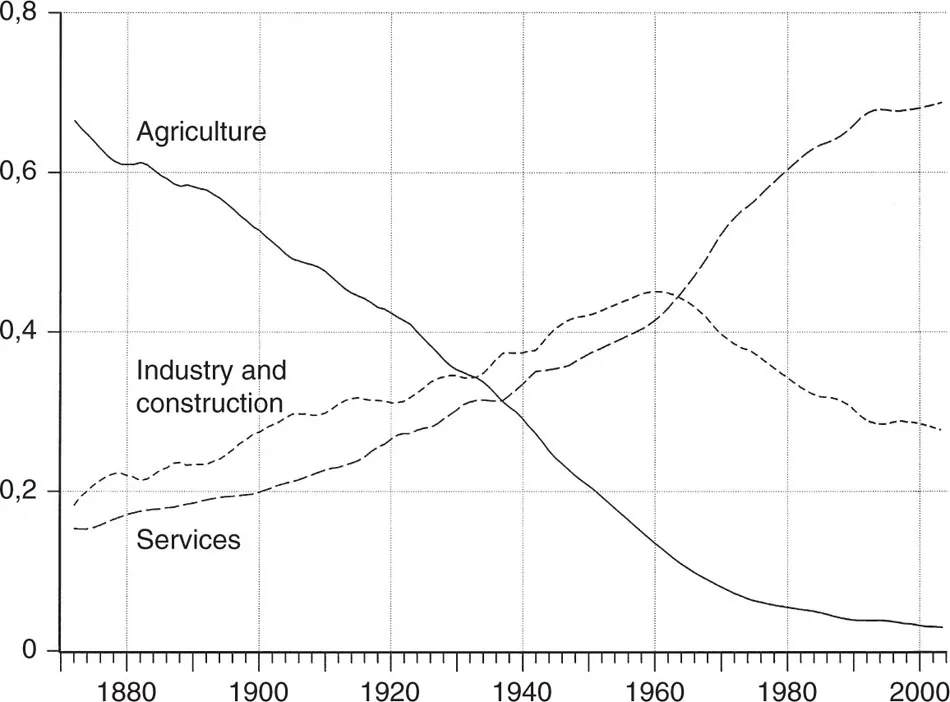

Sweden was transfigured over two centuries from an agrarian society to a modern industrial economy with an expanding service sector. Employment trends since the late nineteenth century demonstrate that dynamic most clearly (Figure 1.2). For most of the nineteenth century, approximately three-quarters of the population worked in the agricultural sector, while one-fourth worked in the industrial and service sectors. Starting in the late nineteenth century, the agricultural sector shrunk steadily and accounted for only a few percentage points by the 1970s. Industry and construction employed more people than any other sector by the 1930s and had expanded to almost 50 per cent by around 1960. However, service sector growth had kept pace with industry and accelerated in the late 1960s. The service sector exceeded 50 per cent around 1970 and by the early 1990s it accounted for the lion’s share of employment, just as agriculture had done 120 years earlier.

Figure 1.2 Shares of employment in agriculture and ancillary industries, industry and construction, and services, 1870–2005. Five-year moving average.

Comment: Services do not include unpaid household work.

Sources: Processing of Jungenfelt (1966), Statistics Sweden, Statistical Annual Accounts, Statistical Communications, National Accounts, Labour Survey, as well as Historical Statistics, Part 1.

Pillars of growth

The fundamental precondition of growth has been an increase in human productivity, which stems from three basic factors. Investment has created productive new resources, innovations have enabled more efficient resource utilisation, and institutions have been designed so as to favour investments and innovations.

The primary purpose of investment was for a long time the development of tangible assets such as tools, machinery, arable land and buildings, as well as transport and communication facilities. Such investment, which permitted the capital accumulation characteristic of agrarian society and the industrialisation process, was generally of the type that promoted the combination of human labour with the energy that people were increasingly able to extract from nature. On the other hand investment in intangible assets – such as the education of a growing population, individual skills development and the acquisition of new expertise, products and market positions by businesses – has taken centre stage in recent decades. The focus of investment has shifted from land to buildings and machinery, and finally to knowledge in its various forms. The greater attention paid to investment in intangible assets over the past few decades has also highlighted its significance during previous stages of economic development.

The above figure illustrates one aspect of the role played by intangible assets in previous eras. The growth of employment in the service sector accompanied the expansion of industry throughout the process of industrialisation. In other words, the emergence of industrial society elevated the importance of services from the very beginning.

Like investment, innovations are future-oriented and represent a component of growth. An innovation permits the factors of production (land, labour and capital) to be combined in a new, more efficient manner. The concept of innovation most often refers to the progressive overhaul of production technology during the past 200 years. The new ways of manufacturing and transporting products that have followed in technology’s wake have also served as a fundamental driver of industrial growth and development. In addition, innovation has generated a host of new products. Apart from some basic commodities such as certain foodstuffs, raw materials and textiles, most of today’s products were nonexistent when industrialisation took off almost 200 years ago.

Growing investment in research and development by universities and businesses provides a major stimulus to innovation. Thus, the entire process of ensuring innovation became more formalised and knowledge-intensive in modern society than ever before.

Innovations may also involve new ways of structuring either production or the economy as a whole. In that sense, they are linked to institutions and institutional change. Institutions are the rules and conventions, as well as the more formal organisations, that govern thought and behaviour in a particular society. Analyses of economic growth in recent years have placed institutions, institutional change, knowledge and skills in the forefront.

The definition and design of ownership rights to the factors of production in a way that stimulates investment and innovation have been fundamental to the social order during economic expansion. In Western countries, private ownership rights to various resources have been extended and incorporated into law. Ownership rights have evolved in interaction with systems of exchange and income distribution. Thus, the markets for products and the factors of production are institutions of fundamental importance to modern Western society. Ownership and markets have jointly shaped income distribution and class structures. But institutional change has not been limited to the broadening of private and individual ownership rights. The goals and responsibilities of national and local governments were redefined and expanded as the market economy extended its reach. Furthermore, industrialisation turned the individual business enterprise into a fundamental institution. Businesses combined market activities with long-term organisational planning, including the development of new types of joint ownership. These various institutions were the backbone of the industrial capitalism that took form in the Western world, starting in the late eighteenth century, and assumed increasingly global dimensions.

The household and the family are also among the institutions that existed before but whose status changed during the emergence of industrial capitalism. After having been the basic economic unit of society, the household morphed into a nuclear family that supplied businesses with labour and consumed their products.

Along with social development in general, the changing role of the household has had a profound impact on another fundamental institution, that of gender identity and the allocation of responsibilities between women and men. Modernisation has frequently forced the patriarchal order that reigned supreme in agrarian society to adapt and loosen its grip.

The dynamic interplay of institutions, innovations and investment has generated growth and transformation throughout the period of industrial capitalism. Both organisations and individuals have made investments, identified new solutions, changed their ways of doing things and established new ground rules. They have created fresh structures and frames of reference, and became the pillars of growth for a certain period of time. Economic history is the story of these organisations and individuals, along with the changing interaction of various social forces.

Most household work – from long-term investments such as childbirth and childrearing to preparation of items for daily consumption – has been performed by women on an unpaid basis. Although the movement of labour from households to the market represented one of the biggest structural changes during industrialisation, unpaid household work is rarely included in GDP or employment figures. One (though incomplete) way to calculate the value of unpaid work performed by women is to multiply the total cost of paid household work by the number of able-bodied women living in the households. In the early nineteenth century, unpaid household work performed by women corresponded to almost half of traditional GDP according to such a calculation (Figure 1.3). The share had declined to approximately one-twentieth around 1990.1

Figure 1.3 Women’s unpaid household work in relation to GDP (excluding unpaid household work), 1800–1995. Current prices: GDP, see Table 1.1. Krantz (1987b), Statistical Annual Accounts, Statistical Communications, Labour Survey.

The significance of transformation

Growth and transformation interact in a complex fashion. Like industrial capitalism in general, growth has run a contradictory course, encompassing both stability and change. Growth depends upon stability. Sustained business relationships, expanded markets, long-term investment and innovation flourish best in a stable atmosphere. Fixed ground rules and organisations that articulate various interests lay the foundation of stability. One such organisation, which is designed to represent the public interest in various ways, is the state. Business enterprises are another type of organisation on which stability is based. They encompass different spheres that are responsible for long-term planning to implement their business concepts. The state, businesses and markets spawn organisations that provide the kind of structure that enables stability. Growth rests on stable structures.

But the growth that arises as the result of investment and innovation changes the prospects for the future. When markets expand, technology evolves and incomes increase, both products and costs are valued differently. In other words, a new price structure emerges. Resources that once were scarce may become abundant, and vice versa. Some needs fall away while others are born. Whatever new direction growth takes, it eventually reaches a limit that demands reorientation. Old enterprises must be phased out and new ones launched. Organisations and ground rules that have supported growth become obstacles, while new opportunities require new conditions. Constant renewal is essential if growth is going to successfully adapt its course. In other words, growth is impossible without the transformation of the directions, organisations and regulations that nourish it. Growth is a battleground between old and new – between those whose interests reside in the way things have been done before and the advocates of renewal.

Renewal and greater efficiency – two ingredients of growth – both entail investments, but of different types. Renewal focuses on doing something differently and better, whereas greater efficiency focuses on improving what is already being done. The ability to renew leads to transformation and to new trajectories of growth. In order to become more efficient, however, growth also requires the need to remain competitive by means of rationalisation.

Renewal automatically generates major investment in buildings and plants, business starts, the acquisition of fresh knowledge and skills, new markets and...