![]()

Part 1

Diversity and Schooling

1 The Challenge of Pluralism

The Pluralist Influence in Schools

A Primary School Example

In 1975 a team of teachers charged in part with investigating the pluralist influence in primary schools was formed as part of an action research project mounted by La Trobe University's School of Education. The team members were drawn from three neighbouring primary schools in one of Melbourne's north-western suburbs, a district which contained a considerable proportion of families from each of a number of southern European ethnic groups.

One of the early tasks undertaken by the team was to make a map showing how the families of the pupil populations of the three schools were distributed over their combined catchment areas. It is true of any major urban centre such as Melbourne that some of its districts have a ‘saturation’ of recent immigrants while others do not. Some areas will be dominated by a single ethnic group. Others will contain large percentages of several such groups. Although the latter case applied in the area where these three primary schools were situated, the members of each of the different groups were scattered over the district rather than clustered together in enclaves—hence the ethnic origin of a family provided no certain clues as to precisely where in the district that family resided. As the map compiled by the teacher team clearly revealed, a native Australian family might well be flanked on one side by a family of Italian origin, on the other by a family from another ethnic group, and be faced across the road by a house inhabited by people from yet another country of origin.

The next task undertaken by the team required considerable fieldwork and much careful interviewing. The team sought the cooperation of the families in an effort to trace the networks of interaction which made up the basic pattern of the neighbourhood's social character. This time the factor of ethnic origin did assume great importance. It was a vital clue to the general pattern of social life adopted by a person or family. There was a greater degree of commonality among people of one ethnic origin in the places where they chose to shop, to spend their leisure time, to worship. To a certain extent the same commonality applied to the types of employment engaged in by families of different ethnic origins.

The degree of commonality just mentioned should not be taken to mean the presence of complete uniformity or anything approaching it. Even less should it be imagined that any one group was discovered to have, so to speak, cornered a particular facility or opportunity. No group was found to have taken over a leisure amenity to the exclusion of any other. The same caution applies to church organisations and to kinds of employment.

Secondly, it cannot be assumed that self-determination alone was at work. For example, neither choice nor random chance alone produces patterns of employment. There were indeed regularities to be observed. Families of one ethnic background were consistently found to have breadwinners in more congenial and profitable occupations than the breadwinners from another group. This was a consequence of the very complex combination of influence and circumstance which occurs in any social environment such as the one in which the team was working. We hope this factor will become progressively more plain in succeeding chapters.

The mapping activities of the teacher team working in the primary schools simply revealed some of the features of social environment, and depicted some evidence of the influences which work within such a context. The work did not explain the dynamic which produced these effects; that was not the intention.

But absence of explanation prevents the growth of the understanding which is a professional essential for the educator in today's world. Lack of insight into the workings of the social environment diminishes the service schools can and should render to the communities they exist to serve. It also distorts the school's contribution to the area's social stability, which should flow from the industries and businesses which draw upon it as a source of work personnel. Understanding of this kind marks the informed and socially capable citizen from any walk of life and is therefore a prime educational goal in a democracy. The team had just begun.

A High School Example

Under the aegis of the same project from La Trobe University another team worked for two years in one secondary school. The area in which this school was situated had many similarities to the one containing the three primary schools, although there was a much greater proportion of immigrant groups than of native-born Australians.1

Over two years of intensive investigation this team studied and analysed the relationships between school staff, pupils and parents. Research in a number of countries has shown previously that a determinant of success or failure in any school programme is the manner in which the programme is supported by all those immediately involved in the process. Coordinated support from the three groups just named is essential2, but it is dependent upon the presence of harmony and goodwill between the groups. These flourish best when the groups share similar attitudes and beliefs on many matters.

After thorough and prolonged preparation, during which the members of this team carefully made themselves acceptable participants in the life of the neighbourhood, a scrupulously administered survey was carried out. Its basis was a nexus of issues which appeared to be of concern to all of the immediate and vital constituent groups in relation to the schooling process. The issues included attitudes and values regarding authority, the suitability of various teaching methods, curriculum content, co-education and the school's role in setting standards of behaviour for pupils to observe beyond the school. In respect of all these issues and a number of others the team discovered deeply held beliefs to exist among teachers, pupils and parents alike. Taken as a whole this set of beliefs greatly affected the relations between the school and the homes of the pupils. It also determined the general reputation of the school as a neighbourhood amenity.

The team now set about ordering the mass of data gained from the survey. For each item in the nexus of issues which had been constructed they compared the responses of the three groups: teachers, pupils and parents.3 The team wished to ascertain the extent to which the beliefs of each group coincided with each other. Did most of the parents agree or disagree with the teachers’ views on co-education, for example? Did the beliefs of the majority of pupils coincide with those of a majority of teachers? And so on for all the items of the survey.

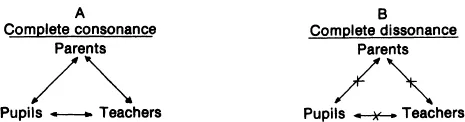

Where there was found to be a coincidence of belief between groups the team indicated this by use of the term ‘cultural consonance’. The overall extent of cultural consonance was determined by the number of issues upon which there was agreement of attitude and belief between the groups concerned. Where there was conflict of belief between groups the team indicated it by use of the term ‘cultural dissonance’. As may be anticipated, the overall measure of dissonance was derived from a similar procedure to that used to determine the extent of consonance. The polarities of complete consonance and complete dissonance are therefore simply schematised as follows:

(From Holdsworth, R. in Claydon4, (ed.) 1975).

Complete consonance: Let us take an issue such as co-education. Consonance would exist if the parent expressed the same belief that there should be co-education as did the pupil and the teacher. If the same could be said in respect of each item in the nexus of issues used in the survey then there would be complete consonance.

Complete dissonance: In respect of the one issue of, say, co-education, dissonance would exist where what the parents thought stood in conflict with what the pupils thought and where both were in some way contradictory to the opinion of the teachers. There would be complete dissonance if this situation pertained for each item of the nexus of issues.

Of course these polarities are more hypothetical than real. There was a mixture of agreements and disagreements across the three groups and over the range of issues. Nevertheless it was possible to chart certain trends of consonance and dissonance between the groups. This was the task of the team. Did one group always, or more often than not, agree or disagree with one or another of the remaining two groups?5 Secondly, the team examined the data in order to discover whether there were any regularities of agreement and disagreement between subcategories within the one group of, say, parents. Did parents of one ethnic group, for example, tend to agree with parents of another ethnic origin but to differ from those of another in respect of this range of important issues?

Both types of regularity were discovered. There was an overall tendency towards cultural consonance between teachers and pupils. There was a tendency to dissonance between pupils and parents and between teachers and parents. There was also found to be an internal pattern of dissonance within the parent group, in which were found three major ethnic divisions and a number of other ethnic representations of smaller numerical strength.

This mix of consonance and dissonance both between and within groups reflects fairly accurately the situation to be found in each of Australia's major cities—and not only in the schools they contain. Cultural pluralism is now the basic social condition of this country, as it is of many others, including the United States of America and Britain. There is increasing recognition of the fact in the recent literature on education and other aspects of social functioning in Australia.6

The work of this team partly explains as well as describes the situation of a school in this context of cultural pluralism. Once the patterns of cultural consonance and dissonance have been revealed and related to the two worlds of home and of school, which we should never forget the pupil must of necessity inhabit, a great deal of uncertainty may be removed. Anticipation of future events becomes much more a matter of calculation than of stargazing and guesswork.

Where there is a basic agreement of belief and attitude between two groups, that harmonious relation is likely to influence both groups when they are confronted jointly with a new issue. By the same token, where a basic conflict of belief and attitude divides two groups, then those groups will often reflect their disagreement when confronting a new issue which requires both groups to make a decision. Their mutual antagonism may invade any aspect of community life which involves them both.

In the event of consonance between groups upon important matters, one group will therefore tend to accept a decision known to be favoured by the other with whom it is in general harmony of belief and attitude. (’If it's OK by them there can't be too much wrong with doing it.’) In the event of dissonance between groups, the fact that one group favours a particular course of action will often be enough to create suspicion and rejection of that course on the part of the other group.

To some extent, the team's work does help us to understand the social situation of the school in which it worked—but there is very much more to be learned and understood before any real power of explanation can be claimed. Nevertheless, the two examples of work by teacher teams suffice to show that schools are institutions affected by a very complicated array of forces. It is only when we, as teachers, employ our skills to gain comprehension of those forces that we begin to see the individual child and the quite ordinary classroom or other school situation in a true perspective. As was said a little earlier, pluralism is a fundamental characteristic of contemporary society. The teams were dealing with the usual situation rather than the extraordinary case.

Versions of the Pluralist Concept

Despite the fact that pluralism is the usual situation, the concept of pluralism is not as familiar or as well defined as some other concepts which have application to our social environment. This is a pity, since it does denote what is almost a defining characteristic of technological and urbanised societies such as Australia. It would be no true service, however, to set down an alleged definition consisting of a mere sentence or so. Instead, it is our hope that, taken as a whole, the contents of this book will provide the reader with a clearer idea of what pluralism means. The specific purpose of the book is to deal with the pluralist phenomenon as it is manifested in respect of schooling. It nevertheless remains the case that to secure success in the enterprise of formal education requires an ever-widening grasp of the principles of social functioning. Parochialism of context and limitations of perspective will not serve the modern teacher.

Plainly, to talk of plurality is to talk of more than one of something. In social terms then, pluralism refers to the variety of basic social groups that exist in a society. Two such groupings which have been found to be of great importance in schooling and level of educational attainment are those of ethnic and racial origin and of socio-economic status.7

These two groupings are frequently systematically related. If a person belongs to an ethnic or racial group other than the one which clearly predominates in the society, he is more likely than not to belong to a particular socio-economic category.8 This is often to be explained by the fact that membership of either group is likely once more to be systematically related to certain levels of educational attainment. There is a discernible trend which allocates pupils of the various social groups, both ethnic and socio-economic, to particular kinds of schools. The reason for this is honestly given as that pupils as individuals require different kinds of educational experience, but the road to group discrimination seems paved by these person-oriented intentions.

Groupings in society are also associated with systems of belief, norms of behaviour, and general ways of conduct both as a public and a private person; i.e. both as a member of the work force and as a father or mother, son or daughter, friend or neighbour, etc. In this book we shall use the term ‘cultural pluralism’ to refer to these different overall lifestyles which distinguish certain social groups.

High and Low Culture

Some further discussion of ‘cultural pluralism’ is perhaps desirable at this point.9 A rather different sense of the concept of culture is frequently associated with education. Qualitative comparisons are drawn to yield talk of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.10 In turn this leads on to recommendations about curriculum content which are based upon arguments for the relative worth or value of some items over others.11 The arguments rest upon contentions about the intrinsic worth of some forms of knowledge, understanding or thought (no one is ever quite sure in the debate as to which of these it is). These forms are favourably contrasted with the merely extrinsic or instrumental value of other things which can be taught and learned. The distinction is often seen to rest upon such factors as the degree to which the item in question is extensible. There is no end to science or to art or mathematics and no specific purposes to which study of them must be directed so that they do not lose meaning. There are, it is argued, limits to most things which have predominantly or exclusively an instrumental value only. Operating a lawnmower is a case in point; it cannot sensibly be done simply for its own sake.12

Other qualities alleged to distinguish curriculum items with intrinsic worth include those of universalisation, truth, objectivity, rationality and morality. The staples of high culture are thought to exemplify what we mean by these concepts. The elements designated to low culture are thought to lack them altogether or to contain them to very limited degree.

These are very important matters. In many ways they are fundamental to any discussion of what is best in man and of what future generations must be brought up to preserve as the essential virtues in a society. In other words the issues define education. They distinguish it from less desirable forms of cultural transmission such as indoctrination.13

Nevertheless we take t...