![]()

Part I

The Origins of Writing

![]()

1 Tokens as Precursors of Writing

Denise Schmandt-Besserat

Writing was invented independently three different times in three different areas on our planet: in the Near East, China, and Mesoamerica. The Near Eastern cuneiform script, created ca. 3200 BC in ancient Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, was the first. It is also the only writing system the origins of which can be traced deep into prehistory (Schmandt-Besserat, 1996). This chapter presents tokens, the system of counters that preceded and led to writing. In particular, it discusses the appearance of tokens in early farming communities about 7500 BC, the evolution of the system over 4000 years, its transmutation into writing in the first cities, and finally, the use of abstraction to create numerals and phonetic signs. Finally, the chapter shows how the identification of tokens as the origin of writing challenged the previous pictographic theory.

THE ORIGIN OF TOKENS

The domestication of plants and animals about 8000 BC transformed ancient Near Eastern society, altering its way of life, economy, and symbolism. Unlike the Paleolithic hunters and gatherers, who were nomadic, the first Neolithic farmers settled down in permanent villages. Leadership changed. Whereas Paleolithic bands were headed by skillful hunters, village leaders were the managers of a redistribution economy. They pooled together contributions from the community in order to redistribute the goods for the benefit of all. Counting became a necessary skill to compute the communal resources and manage the collective flocks and granaries. In order to fulfill these tasks, tokens were created to count and account for staple foods, in particular animals and quantities of cereals.

That the creation of tokens coincided with the beginning of agriculture is well established by the modern archaeological excavation techniques and C-14 dating. In particular, in Syrian as well as Iranian archaeological sites, the earliest tokens are repeatedly recovered together with the first evidence of cereal cultivation ca. 7500 BC. Collections of tokens excavated in sites of the seventh to fourth millennium BC document how the system spread over the entire Near East from Palestine to Turkey and from Syria to Iran and its evolution over 4000 years, until it was supplanted by writing in cities of the late fourth millennium BC.

THE TOKEN SYSTEM

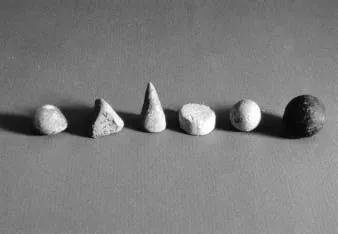

The tokens were modeled in clay in many shapes. The earliest examples assumed mostly geometric forms such as cones, spheres, cylinders, ovoids, disks, and tetrahedrons (Figure 1.1). The arbitrary, simple, and striking geometric shapes proved key to the success of the system because they were easy to identify, to remember, and to replicate. Moreover, the surface of the clay tokens could be easily marked with lines, dots, or attached pellets for additional information.

The use of clay as a raw material can also be credited for the widespread diffusion of tokens. Because clay is easy to model when moist, the manufacture of tokens was simple. It merely consisted of pinching a small lump between the fingers, with no tool or skill necessary. Sun drying or baking in the fireplace made the counters hard and their shape permanent. Furthermore, because clay is common and easy to collect around river banks, ponds, and water holes, the system could be passed on from one village to another and from one culture to the other. Lastly, the tokens were small, measuring about 1–3 cm across, and therefore the quantities of clay required to make the necessary counters were minimal. In sum, the accessibility of the material, the simplicity of manufacture, and the geometric format of the tokens were responsible for the rapid adoption of the system in the Neolithic agricultural economies of the ancient Near East and its continuity over many centuries.

FIGURE 1.1 Tokens from Tepe Gawra, present day Iraq, ca. 4000 BC. Cone, sphere, and flat disk are three measures of cereals: small, larger, largest. Tetrahedron is a unit of work (one man/one day). (Courtesy the University Museum, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.)

TOKENS AS SYMBOLS FOR COMMUNICATION

The tokens represented a new symbolic system for communication. Each token shape was a symbol for one particular unit of goods. For example, a cone represented a small measure of grain (equivalent to a liter); a sphere stood for a large measure of grain (equivalent to a bushel); a cylinder for an animal of the flock (either a sheep or a goat); and an ovoid for a jar of oil. The earliest token assemblages of the eighth millennium BC included a mere dozen shapes, which seemingly represented all the commodities managed at the time. The objects served as a code to store, manipulate, and exchange all the economic information necessary for the Neolithic redistribution economy. Anyone initiated with the meaning of the token shapes could understand and translate into words the specific accounts of goods represented by a given set of the counters. Seen from the twenty-first century, the great limitation of the system was, of course, that the tokens could only communicate economic information, namely numbers of units of given merchandise. They were unable to convey any other kind of data.

TOKENS AS SYMBOLS FOR ACCOUNTING

Tokens made accounting possible. They represented a notable advance compared to the previous notched bones or sticks. The Paleolithic tallies merely indicated the number of units of a single unspecified commodity, but the tokens of many shapes, each designating a specific unit of merchandise, made it possible to keep track of multiple goods simultaneously. When necessary, new token shapes could be created to record additional types of goods. Another great advantage of using counters for accounting was to make a complex budget visible. The number of tokens representing amounts of goods signaled at a glance which of the commodities were abundant and which were scarce. Furthermore, the counters made it possible to keep track of present, as well as past or future, transactions, such as debts or pledges.

TOKENS AS SYMBOLS FOR COUNTING

Tokens also influenced counting. The system was based on one-to-one correspondence, that is to say, one small measure of grain was shown by one cone, two by two cones, and so on, which is the simplest and also the most rudimentary form of counting. On the other hand, the multiple shapes of tokens denote “concrete counting,” an archaic counting system characterized by using different number words—numerations—to count each type of commodity. Numerical expressions such as “twin, triplet, quadruplet” referring to children of the same birth, or “solo, duo, trio, quartet” referring to numbers of musicians, give an idea of the concept of concrete counting. For example, the term “duo,” like a concrete number, fuses together two concepts: two and musician, without the capacity of separating them. Concrete counting prevented units of different kinds from being computed together. Also, the special numerations were limited to one to ten or a dozen concrete numbers so that, for example, when more than nine animals were in the group, counting switched to a nonspecific group term such as “a flock” or “a herd.”

There can be no doubt that the use of tokens enhanced counting by facilitating the chunking of units of the same kind of goods to build larger numbers or “sets.” For instance, animal counting included two tokens: a cylinder and a lenticular, disk standing respectively for “one animal” and “a flock” (10 sheep or goats). Because the large units were also used in one-to-one correspondence, they stretched the ability to count beyond the usual 10 or 12 units of a simple concrete numeration. For instance, three lenticular disks stood for “three flocks,” probably “30 animals.” This paved the way to the systematic creation of larger numbers and arithmetic. On the other hand, it is evident that, during the prehistoric period, the five common measures of grain represented by tokens in the shape of a cone, a sphere, a large cone, a large sphere, and a flat disk did not represent precise quantities, but stood for informal daily life containers such as a cup, a basket, and a granary. Furthermore, these were neither standardized nor conceived as numerical units, that is, as multiples of one another.

TOKENS AND STATE FORMATION

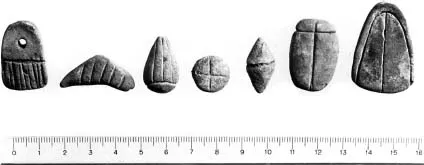

The tokens remained unchanged for 4000 years. In 3500 BC, when Mesopotamian and Elamite settlements grew into towns and cities, in present day Iraq and Iran, the temple and palace economies were still managed solely with the token system. But, about 3300 BC, the creation of the state signified a new level of complexity for accounting, when the contributions of goods in kind became mandatory taxes. As the number of goods levied by the state increased, additional token shapes were created. Consequently, new tokens of triangular, rectangular, oval, and parabolic shapes appeared, many of them covered with sets of incised lines or impressed dots (Figure 1.2). Among the new registered products were domestic and imported raw materials such as wool and metal; processed foods like bread, oil, beer, honey, and trussed ducks; and goods manufactured in urban workshops, such as textiles, garments, rope, mats, carpets, tools, furniture, jewelry, and perfume.

FIGURE 1.2 Tokens from Susa, present day Iran, ca. 3300 BC. Starting above from left to right: one garment, one ingot of metal, one jar of a particular oil, one ram, one measure of honey, one garment. (Courtesy Musée du Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, France.)

The collection of tokens recovered in the Sumerian city of Uruk numbers as many as 250 shapes, compared to the dozen forms typical of Neolithic assemblages. This suggests that, by the late fourth millennium BC, the complex token system was handled by specialists. The manufacture of tokens was also more elaborate. The clay used to model the late fourth millennium tokens was finely prepared and free of inclusions. They were well fired, exhibiting an even pink color throughout their thickness. Some of the shapes were quite elaborate, featuring objects such as jugs, tools, furniture, and animal heads in miniature size.

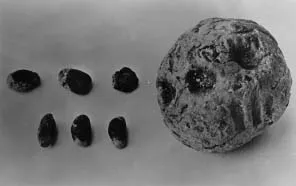

ENVELOPES TO STORE TOKENS

After the middle of the fourth millennium BC, the city-state administration became concerned with storing accounts of tokens featuring debts, probably unpaid taxes. Envelopes were created to hold securely the tokens representing the amount due until it was paid. The envelopes were hollow clay balls, some 5–9 cm across. Tokens were placed inside the cavity and the opening was closed with a patch of clay (Figure 1.3). The envelopes were practical since they could be quickly made and could hold tokens for any length of time. More importantly, the clay surface was ideal to imprint seals indicating the parties involved—debtors as well as the responsible officers of the state administration. These Near Eastern seals were small stone artifacts carved in negative with a unique pattern, which served as identification of offices as well as individuals. Each of the some 150 envelopes recovered had from one to four seals carefully impressed over their entire surface, ensuring that no tampering could occur. The envelopes proved useful and became popular throughout the Near East, as illustrated by the specimens still holding tokens recovered in Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Iran, and as far south as Saudi Arabia.

FROM TOKENS TO WRITING

The envelopes set the token system onto a new course that, after a series of rapid transformations, finally climaxed with the invention of writing. The first major change took place about 3300 BC, when the envelope was used to carry new information. After affixing the seals, the accountants imprinted on the surface of the envelopes the tokens to be enclosed inside. As a result, a cone left a wedge-shaped mark and a sphere a circular one. In other words, the three-dimensional tokens held inside the envelopes were reduced to two-dimensional signs on the outside of the envelope (Figure 1.4). This simple invention, only meant to conveniently make visible the content of an envelope without opening it, turned out to be a remarkable new communication system. It was the invention of writing.

FIGURE 1.3 Envelope and its token content, ca. 3300 BC, from Susa, Iran. The lenticular disks and corresponding large circular signs each stand for “a flock” (10 animals). The cylinders and corresponding thin wedges represent 33 of one animal (sheep or goat). (Courtesy Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, France.)

FROM ENVELOPES TO TABLETS

About 3200 BC, the complicated system of hollow envelopes featuring tokens inside and their corresponding impressions outside was simplified. Tokens became imprinted on solid clay balls—tablets (Figure 1.5). The wedges and circular signs standing for cone and sphere tokens no longer duplicated actual tokens but had become independent entities. They constituted a script. But, although the form of the symbols had changed, the written signs were semantically identical to their token prototypes. Like tokens, each sign stood for one unit of a particular commodity. Also like tokens, the signs were used in one-to-one correspondence: two wedges represented two small measures of grain and three circular markings stood for three bushels of grain. Finally, like the token system, the early written texts dealt exclusively with goods. In 3200 BC, writing consisted of a repertory of logograms, each conveying the concept of one specific unit of goods.

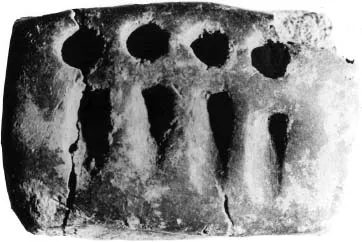

FIGURE 1.4 Impressed tablet from Godin Tepe, Iran, ca. 3100 BC. The circular signs stand for one large measure of grain, the wedges for one small measure of grain. (Courtesy Cuyler Young Jr., Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.)

FIGURE 1.5 Incised tablet, from Godin Tepe, Iran, ca. 3100 BC. The impressed signs are numerals. The circular signs stand for 10 and the wedges for 1. The signs on this incised tablet represent 33 measures of oil (10 × 3) + (1 × 3). (Courtesy Cuyler Young Jr., Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.)

NUMERALS

About 3100 BC the images of some tokens started to be drawn on the tablets with a stylus, instead of being pressed into the clay. The new incised technique had the advantage of representing more accurately the outline of tokens and their various markings. But far more than the shape of signs was changed. The incised signs were no longer repeated in one-to-one correspondence to indicate the number of units of goods. Instead, they were preceded by numerals—signs expressing one, two, three, and so on abstractly. For the first time, the concepts of oneness, twoness, threeness were abstracted from the goods counted and the signs to express “one,” “two,” or “three” became applicable to multiple commodities. Surprisingly, no new signs were created to express numerals. Instead, the units of grain, which continued to be impressed, took a new numerical...