![]()

Part 1

Psychological perspectives: Short-term and working memory

![]()

1 Working memory still working

Age-related differences in working-memory functioning and cognitive control

Paul Verhaeghen

AGING AND WORKING MEMORY: DEFICITS AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES

Working memory is often considered the workplace of the mind. It refers to a temporary memory buffer—lasting for a few seconds at most—which is able to passively store and actively manipulate information (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Kane, Bleckley, Conway, & Engle, 2001; Miyake & Shah, 1999). Working memory can be (and has been) studied under quite a number of aspects, such as its structure, the processes that ensure its smooth operation, and its functionality in the broader context of the cognitive system. It is pretty safe to say that there are about as many takes on these aspects as there are researchers (Miyake & Shah, 1999, have an excellent overview of the main theories), but some general principles do stand out.

First, in terms of structure, many theorists (perhaps first and foremost Cowan, 2001, in his embedded working-memory model) assume a hierarchy of availability where the amount of information that is available for immediate access is severely limited (depending on the task, one to four items; Verhaeghen, Cerella, & Basak, 2004). Additional items can be accommodated in a different store—in lay terms, “the back of your mind”—where, although information is not immediately accessible, it remains in a state of heightened activation and thus can be retrieved with relative ease (e.g., Oberauer, 2002). The terms I will use here for these two types of stores are focus of attention (Cowan’s 2001 coinage) and outer store. For instance, while cooking a curry with friends, you might need to focus all your attention on cutting peppers and carrots. At the same time, you need to realize that your onions are cooking and not lose track of the exact moment when the spices need to be added to the onions—when they are just past golden brown, not much later. The focus is on the knife, the pan with onions is in the outer store, and from time to time the contents of both will need to be swapped to prevent a culinary (and social) disaster.

Second, in terms of processes, many theorists posit that an efficient working memory is helped by a host of control processes sometimes labeled “executive control” processes and sometimes “cognitive control” processes. I will use the terms interchangeably (e.g., Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000)—task scheduling, shuffling items in and out of the focus of attention, updating the contents of the focus or the outer store, shielding information from interference, and the like. In the cooking example, at some point you might need to focus your attention wholly on the slicing, then broaden it to include conversation with your friends when the task permits (rinsing the vegetables is a good one), and then again switch it from, say, cutting the carrots to stirring the spices into the browned onions. In general, you also need to update the contents of working memory continuously, making sure you know how the curry is progressing and that the next step in the cooking process is always clear and prepped.

Finally, in terms of functionality, researchers like to quantify the workings of working-memory system in a global measure called working-memory capacity: Subjects perform complicated working-memory tasks (e.g., remembering words while also solving arithmetic puzzles) and the number of items they can retain in the face of the interfering tasks and/or items is measured. This capacity is then correlated with other aspects of the cognitive system (e.g., Engle, Kane, & Tuholski, 1999). The underlying reasoning is that an effective working-memory system is crucial for high-level performance in a plethora of cognitive tasks, presumably because an effective working-memory system depends on the efficient implementation of the aforementioned cognitive control operations, which are fundamentally involved in all aspects of the cognitive system. (Obviously, anyone who pulls off the feat of perfect curry must be smart in other domains of life as well.) This type of research has indeed confirmed that significant relations exist between fluid intelligence and working-memory capacity, and between spatial and language abilities and working memory, among others (e.g., Conway, Cowan, Bunting, Therriault, & Minkoff, 2002; Engle et al., 1999; Kemper, Herman, & Lian, 2003; Kyllonen, 1996; Salthouse & Pink, 2008). These correlations are quite respectable in size: In their metaanalysis, for instance, Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle (2005) conclude that the average correlation between working-memory capacity and markers of general fluid ability (g) is .36 (.48 after correcting for unreliability).

The nature of age-related deficits in working memory has received much research attention, precisely because of working memory’s functional implications. The brunt of the research shows that working-memory capacity declines with advancing adult age. Small age differences are already found in short-term memory tasks that do not require much cognitive control or attentional resources, such as digit span tasks. Age-related deficits in working memory, as measured by tasks such as reading span, listening span, or operation span, are demonstrably larger. For instance, in a meta-analysis compiling a total of 123 studies from 104 papers, Bopp and Verhaeghen (2005) found a systematic relationship between working-memory capacity measures of younger and older adults: Capacity of older adults could be well described (R2 = .98) as a simple fraction of that of younger adults. Older adults’ capacity in simple short-term memory span tasks was 92% that of the capacity of younger adults; their capacity on true working-memory tasks, however, reached only 74% that of younger adults.

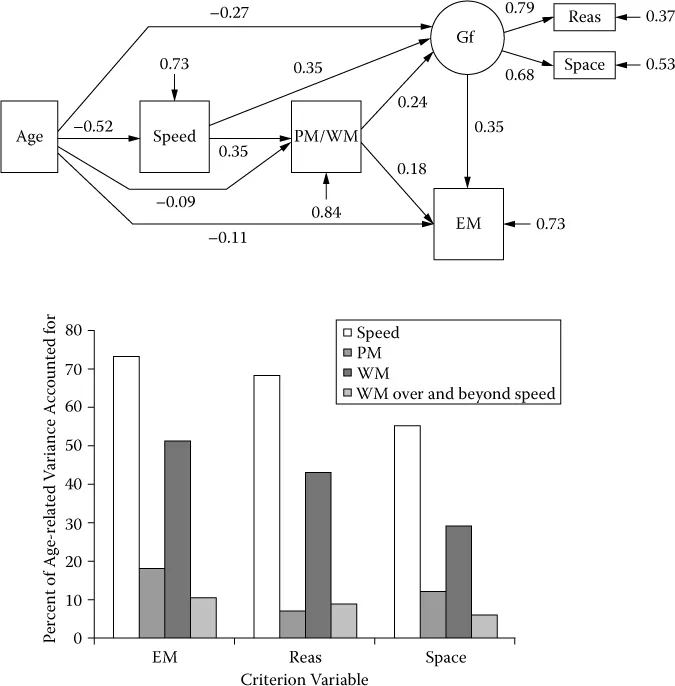

Given working memory’s central position in the cognitive system and given age-related declines in its capacity, it is not surprising that working memory explains a substantial part of the age-related deficits observed in higher order aspects of cognition. Figure 1.1 reproduces a relevant path analysis based on a large-scale meta-analysis of the literature (Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997), as well as estimates of age-related variance in each of three criterion variables (episodic memory, reasoning ability, and spatial ability) accounted for by processing speed, short-term memory capacity, and working-memory capacity. Depending on the criterion variable, working-memory capacity explains between 30% and 50% of age-related variance, and short-term memory capacity explains much less—between about 10% and about 20% of variance; processing speed explains more—55% to 70%. Importantly, working-memory capacity reliably explains age-related variance over and above the variance already explained by processing speed—the cognitive primitive that is typically most clearly associated with age-related differences in cognition (for a review, see Salthouse, 1996) between 5% and 10%. Combined, then, speed and working-memory capacity account for 60% to 80% of age-related differences in higher order cognition.

All of this suggests that the study of age-related differences in working-memory capacity and its causes and consequences might be a worthwhile endeavor. In the remainder of this chapter, I focus on one class of explanations for its decline and its downstream effects on higher order cognition: those in terms of cognitive control. As stated previously, efficient cognitive control is needed to create an optimally effective working-memory system; these control processes are likely responsible for the close link between working-memory capacity and fluid aspects of cognition (e.g., Heitz et al., 2006).

First, I will give a broad overview, largely based on meta-analysis conducted in my lab; next, I will turn to our own experimental research dealing extensively with one aspect of control: working-memory updating, as examined through the concept of focus switching. Some of the studies in this area of research emphasize the neuropsychological bases of cognitive and executive control and call attention to associations between selected memory deficits and the consequences of brain aging on specific functions associated with the prefrontal and midfrontal regions of the human cortex (e.g., Moscovitch & Winocur, 1995; West, 1996). Alternatively, some researchers take a more integrated view of brain aging effects that includes the integration of multiple brain regions and distributed brain functions (e.g., Adcock, Constable, Gore, & Goldman-Rakic, 2000; Braver et al., 2001; Rosen et al., 2003; Small, Tsai, deLaPaz, Mayeux, & Stern, 2002). I note that my overview will remain firmly at the behavioral level.

FIGURE 1.1 Working memory mediates age-related differences in higher order cognition. Top panel: path analysis from a large meta-analysis reported by Verhaeghen and Salthouse (Verhaeghen, P., & Salthouse, T. A., 1997. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 231–249.) PM / WM = primary memory/working memory; EM = episodic memory; Gf = general fluid ability; Reas = reasoning ability; Space = spatial ability. Bottom panel: reanalysis of these data showing percentages of age-related variance in episodic memory, spatial ability, and reasoning ability explained by speed of processing, short-term memory, and working memory, as well as variance explained by working memory over and beyond variance explained by age.

AGING AND COGNITIVE CONTROL

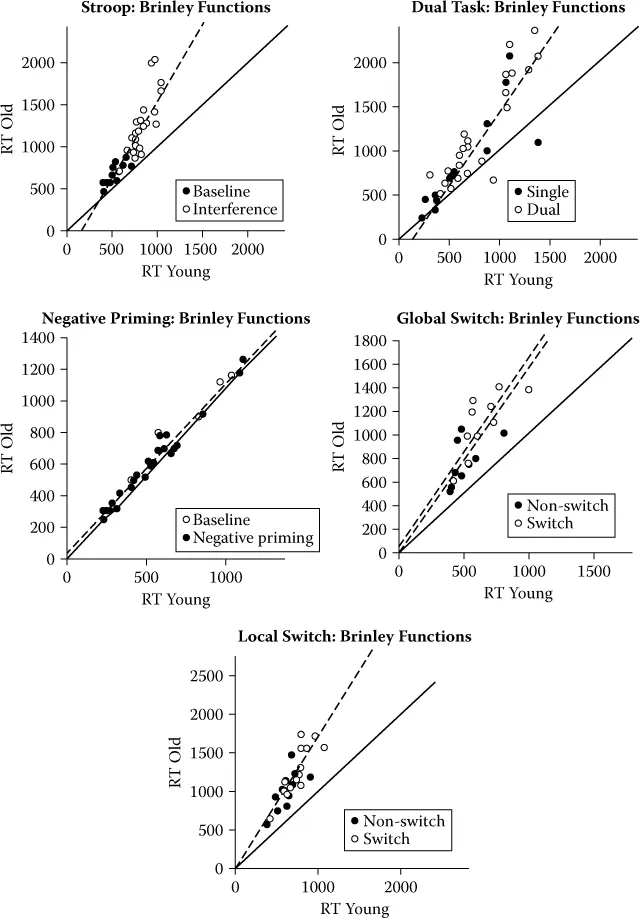

Control processes have been researched extensively in the field of cognitive aging, but little attempt has been made to tie these efforts to a coherent framework. My own reading of the literature (notably the factor-analytic efforts by Friedman & Miyake, 2004; Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999; Miyake et al., 2000; and Oberauer, Süß, Schulze, Wilhelm, & Wittmann, 2000) suggests that cognitive control can be studied under at least four aspects: resistance to interference, coordinative ability, task switching, and memory updating. I will discuss these in turn, relying heavily on our own meta-analytic work (reviewed in Verhaeghen & Cerella, 2002, 2008; Figure 1.2 presents an overview of these studies).

First, resistance to interference, also known as inhibitory control, was a central explanatory construct in aging theories throughout the 1990s (e.g., Hasher, Tonev, Lustig, & Zacks, 2001; Hasher & Zacks, 1988; Hasher, Zacks, & May, 1999; Lövdén, 2003; for a computational approach, see Braver & Barch, 2002). Inhibition theory casts resistance to interference as a true cognitive primitive and posits an age-related breakdown in this resistance. This breakdown would in turn lead to mental clutter in an older adult’s working memory, thereby limiting its functional capacity and perhaps also its speed of operation.

The Stroop task and negative priming are the procedures most often used to test for age differences in resistance to interference. In the Stroop task, participants are presented with colored stimuli, and have to report the color. Response times (RTs) from a baseline condition where the stimulus is neutral—for instance, a series of colored Xs—are compared with RTs from a critical condition in which the stimulus is itself a word denoting a different color than the one that it is presented in (e.g., the word “yellow” printed in red). Response times are slower in that case, due to interference from the meaning of the word. In the negative priming task, participants are shown two stimuli simultaneously; one is the stimulus to be evaluated (the target), while the other is the stimulus to be ignored (the distracter). For instance, the participant can be asked to name a red letter in a display that also contains a superimposed green letter. If the distracter on one trial becomes the target on the next (the critical, negative priming condition), reaction time is slower than in a neutral condition where none of the stimuli are repeated (the baseline condition). Note that this effect is counterintuitive: Higher levels of inhibition are associated with larger costs.

The approach we (Verhaeghen & Cerella, 2002, 2008; Verhaeghen & De Meersman, 1998a, 1998b) have taken to investigate age differences in these processes is to examine whether the presumed age-related deficit observed in the condition requiring high levels of cognitive control (e.g., in the case of Stroop, the color–word condition) is larger than that in the condition requiring lower levels of cognitive control (e.g., in the case of Stroop, the Xs condition). To do so, we use a technique pioneered by Brinley (1965); the Brinley plot is a scatter plot with mean performance of younger adults plotted on the X-axis and mean performance of older adults on the Y-axis. The early plots typically showed that a single straight line (with a small, usually negative intercept), and hence a single linear equation, could describe data drawn from multiple conditions or tasks quite well. A straightforward interpretation of this functional relationship is in terms of speed of processing: older adults are slower than younger adults by a certain constant near-multiplicative factor, regardless of task (Cerella, 1990).

FIGURE 1.2 Brinley plots from meta-analyses on aging and different measures of cognitive control—Stroop, negative priming, dual-task performance, global task switching, and local task switching. (From Verhaeghen, P., &a...