![]()

1

The Problem of Classroom Control

Schoolteachers operate in loco parentis. Their rights and duties are taken to be the same as that of a parent to his/her child and, in this sense, the law sanctions the exercise of discipline within tolerable bounds (Barrell, 1975). Indeed, in some respects such as matters of pupil safety, it places upon the teachers a clear obligation to restrain aspects of pupil behaviour and control their behaviour ‘as any parent might expect to do’. For example, as a result of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, classrooms, laboratories, workshops, corridors, playgrounds and even official outside visits have come under the auspices of safety legislation, and action could be taken against a teacher if an accident could be attributed to negligence in exercising control. Clearly then, the law places upon the teacher an obligation to control the pupils in his/her charge and provides what can be seen as an official mandate for control. As Stenhouse puts it,

The teacher is sent into the classroom with a legitimate power and authority, vested in him by society through legislation and through custom. This authority carries with it a responsibility to exercise some control over the life of the class.

(Stenhouse, 1967, p.47)

The exercise of this control, like other aspects of teachers’ work, receives a good deal of scrutiny by the public. One reason for this is that during their time as pupils, members of the public will have built up considerable firsthand experience of the situation within which teachers work, and perhaps feel as a consequence that they are privy to the demands facing teachers and pupils. This familiarity with school life puts the public in a position to express opinions and preferences about schooling and comment on the performance of teachers in a way that they would not feel justified in doing with most other occupations. The public knows something about teaching and can, therefore, judge the work of teachers more easily than that of bank-clerks, quantity surveyors, accountants or computer programmers. The public’s knowledge, as teachers will be quick to point out, is likely to be highly selective and usually well out-of-date but this does little to detract from the rather unique position in which teachers find themselves.

The result is that teachers find themselves more exposed to public debate and political controversy than most other occupations. This has been particularly evident in the educational debates of recent years where the quality of teachers and the nature of their teaching have been subject to a series of public interrogations. The reorganization of secondary education proposed in Circular 10/65, for instance, sparked off an increased intensity of debate about matters like the organization of schools, the methods used in schools and the proficiency of the teachers involved in the system, and the Black Papers, the Bullock Report and Mr Callaghan’s ‘Great Debate on Education ’ have all invited a detailed and public scrutiny of the work of teachers.

From such public debates it seems clear that on matters of schooling and education there are three major areas of concern in the public’s mind. First, there is the question of literacy, numeracy and general standards of academic attainment. Second, there is a public concern with the relevance of education for meeting the demands of today’s technology and commercial needs. Third, the public is anxious about the ability and willingness of school teachers to control their classes and get what is loosely called ‘discipline’ in lessons. Gallup polls in the United States have shown that parents there regard it as the biggest problem facing schools (Curwin and Mendler, 1980) and in Britain, as well, a public concern with discipline in schools continues to rival questions about curriculum and falling standards of education for top spot in the anxiety ratings. In the case of Britain, there have been persistent allegations of declining standards of discipline and control, especially in the comprehensive schools. These allegations have come mainly from the more right-wing press, politicians and teachers for whom the levels of violence, vandalism and indiscipline in the schools bear testimony not only to a general social decay but also to a specific malaise associated with teaching. This line of thinking was clearly evident in the series of Black Papers (Cox and Dyson, 1969–70; Cox and Boyson, 1975, 1977) in which progressive teaching methods and poor quality teaching were ‘held responsible for an alleged decline in general standards and basic skills, for a lack of social discipline and the incongruence between the worlds of school and of work’ (Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, CCCS, 1981, p. 212). Time and again the tabloids and right-wing press have fanned the flames of the controversy with alarmist reports of violence, vandalism and truancy of crisis proportions and, as the contributors to Unpopular Education discovered when analysing the coverage of educational matters by the Daily Mirror and the Daily Mail between 1975 and 1977,

What was presented as ‘debate’ was in effect a monologue concentrating on items concerning teachers’ lack of professional competence or the negative aspects of pupil behaviour.

Central to the reporting were pictures of the current state of British schooling. Images of incompetence, slovenly, subversive or just trendy teachers who had failed to teach or control the indisciplined pupils in their charge became too familiar to need elaboration.

(CCCS,1981, pp. 210–11)

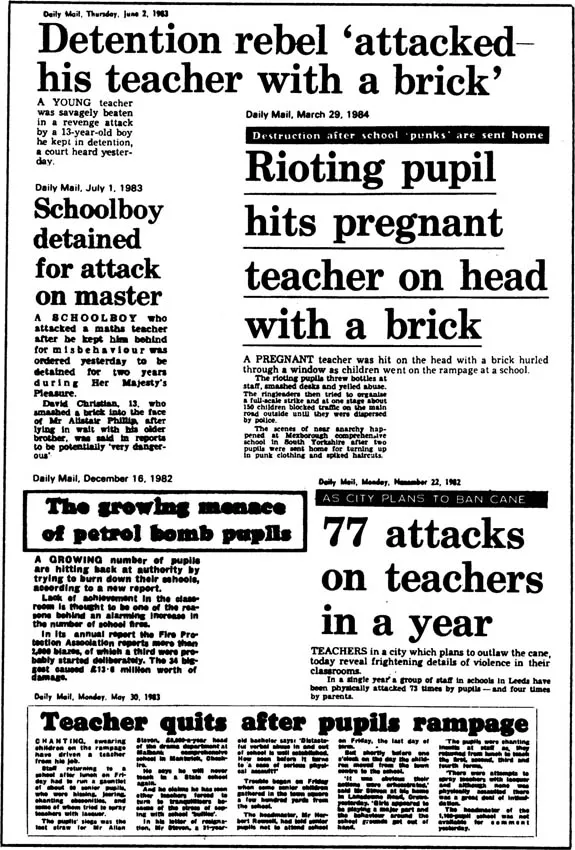

Recent reporting by the Daily Mail would suggest that things are much the same, with violence, vandalism and arson continuing to capture the headlines (see Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1 A bad impression

Such reporting is based, in part at least, on the premise that the newspaper is expressing public opinion as well as informing it and as the CCCS writers comment about the period of their study:

There were confident assertions that ‘millions of parents are desperately worried about the education that their children are receiving’ (Daily Mail 27.4.76) and that ‘parents’ throughout the country are becoming increasingly frustrated by the lack of discipline and low standards of state schools (Daily Mail 18.1.75)

(CCCS, 1981, p.214)

Whether as a cause or a consequence of press reporting there does appear to be some substance to these claims. Wilson (1981), for example, found that 99 per cent of the parents he interviewed felt that discipline was not adequately enforced in schools and the image of schools held by the parents in his study was one in which teachers were becoming bullied and intimidated by their teenage pupils.

The teaching profession itself has not been immune to the idea that classroom control is a major contemporary problem. Part of the policy of the National Association of Schoolmasters and Union of Women Teachers (NAS/UWT) over the last decade, for instance, has been to expose what it regards as the very real crisis of control in schools and to draw attention to ‘the facts’ about violence, vandalism and truancy in schools (Comber and Whitfield, 1979; Lowenstein, 1972, 1975). Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Schools (HMI) have added their professional voice to the growing chorus. As they concluded in their report, The New Teacher in the School (HMI, 1982b) one-quarter of the new teachers they observed were not adequately prepared for the job when they entered the profession. Some of the lack of preparation concerned the level of proficiency in the subject specialism and some of it the match between the subject qualification and the kind of job the new entrant first took up in school. Significantly, though, much of the criticism concerned the preparation of newcomers to deal with matters of classroom organization, management and control. There are clear indications that HMI would like to see more attention given to such skills in the content of initial teacher training (HMI, 1982a) because where new teachers struggle in class it frequently appears to be due to a lack of control (HMI, 1982b). Summarizing the nature of the least successful lessons they had witnessed, HMI point out that the

Characteristics most commonly associated with lessons of low quality included … poor relationships and class control, particularly in the secondary schools, where occasionally these seriously inhibited the teaching and rendered meaningless any comment on other aspects.

(HMI, 1982b, p.23)

The rapid growth of ‘special’ schools and units for maladjusted pupils in recent years might also been seen as an acknowledgement on the part of the teaching profession that there is a real, and worsening, problem of control in schools. As an HMI report noted, ‘The widespread provision of units for disruptive pupils is a relatively recent phenomenon, the bulk of them having been established in or since 1974’ (HMI, 1978, p.41). By 1977, sixty-nine of the ninety-six local education authorities had special schools or units mainly catering for pupils of secondary school age (72.1 per cent). The total provision in England at that time consisted of some 3,962 places in 239 schools/units. Such special schools and units, as it happens, were never intended to deal solely with problems of discipline and control arising from particularly disruptive pupils. They were intended to cover a number of psychological disorders contained under the umbrella term ‘maladjustment’ ranging from nervous disorders, habit disorders, organic disorders, psychotic behaviour and specific educational difficulties as well as behaviour disorders (Laslett, 1977b, pp.48–9). But as Dawson (1980, p. 13) found from his survey, pupils with ‘conduct disorders’ (that is socially unacceptable behaviour such as aggression, destructiveness, stealing, lying, truanting and so on) formed about 76 per cent of pupils in these schools. It is with some justification, then, that special schools and units have come to be regarded as ‘sin bins’ where particularly disruptive pupils get sent away from the normal classroom. Their rapid growth during the 1970s might be seen, on the surface at least, as symptomatic of an increasing problem of control.

A crisis of control?

The picture of classroom control presented so far is clearly one of the declining standards of discipline and a developing crisis of control in schools. But this is not the whole picture because we need to weigh against this impression a number of research findings which suggest instead that a far more cautious and qualified position is justified (Docking, 1980; Galloway et al., 1982; Jones-Davies and Cave, 1976; Laslett, 1977a). Historical evidence, for example, casts doubt on the idea that the control problem is anything new to schools (Grace, 1978; Humphries, 1981; Swift, 1971) and, as Galloway et al. conclude:

The evidence does not suggest that schools today are any closer to anarchy, than they were in the 1920’s and 1930’s … The limited available evidence lends no support to the notion of a large increase in the number of pupils presenting problems, or in the severity of the problems they present.

(Galloway et al., 1982, pp.11, ix)

Humphries, emphasizing the point, produced evidence of severe disruption in schools during the period 1889–1939 specifically to

challenge the popular stereotype and academic orthodoxy that portrays pupils in the pre-1939 period as disciplined, conformist and submissive to the school authority [and to] expose this misleading stereotype by tracing the extensive nature of pupil opposition to provided schools.

(Humphries, 1981, p.28)

Swift (1971) points out that, in the United States, control difficulties have an even longer history. As far back as 1837 the records show that 10 per cent of Massachusetts’ schools were broken up by rebellious pupils. This kind of information should make us wary about getting caught up in any hysterical response to a ‘new crisis’ of classroom control. It does not prove that things have always been the same but it does warn us against a blind acceptance of the common sense truth that control problems are worse than they used to be.

The second reason for caution concerns the evidence of violence. If, for the purposes of the present discussion, we turn a blind eye to corporal punishment as a form of institutionalized violence administered by teachers on pupils (and since 111 of Britain’s 125 local education authorities still permit corporal punishment this is quite a significant narrowing of the whole issue) then it seems that violence in schools is actually quite rare. Mills (1976), for example, on the basis of extensive research on 13–16 year old pupils in the Midlands, found that the chances of a teacher being actually assaulted were very low and that within the area studied there appeared to be a hard-core of only about 3 per cent of this age-range who could be identified as ‘seriously disruptive children’. Even Lowenstein’s (1972) inquiry for the NAS in which it was claimed that ‘the amount of varied violence occurring both in secondary and primary schools [was] much larger than might have been anticipated from the occasional press report’ (p.25) did not actually uncover a picture of extensive violence in schools. Of the 1,065 questionnaires returned by NAS representatives in secondary schools (from 4,800 sent out), 443 reported ‘no real problem of violence’ in their schools. Of the 622 who reported the existence of violence in their schools, only 66 said it was frequent. Furthermore, the kinds of violence reported were not always matters as serious as assaults on teachers or other pupils. There were many more reports of violence against property than of violence against the person.

My own fieldwork in Ashton, Beechgrove and Cedars served to reinforce the idea that physical violence aimed at teachers by pupils is relatively rare. Certainly, there were some incidents that matched the atrocity stories to be found in sections of the press. One, in particular, was horrific. During fieldwork at Beechgrove a teacher was stabbed in the back with a chisel. She suffered a punctured lung and did not return to teaching when she eventually recovered. Fortunately, this incident was the only very serious piece of violence against a teacher or pupil that occurred. There were probably a number of milder assaults on teachers during the period of research and certainly at Beechgrove a male chemistry teacher, quite small in stature, even developed something of a reputation for getting assaulted by pupils. On two separate occasions I actually witnessed during fieldwork he was punched repeatedly on the chest and had abuse shouted at him by pupils who seemed to have completely lost their temper. Interestingly, on neither occasion did the boy (a different one each time) hit the teacher in the face, stomach or elsewhere that would have caused real injury and the attacks were actually, consciously or otherwise, controlled and limited in their viciousness. The teacher was left standing and, before the pupil could be constrained by other teachers, was warning the boy, ‘Your’re in a lot of trouble already doing this. I’d stop now if I were you before you go too far.’

Gauging from the fieldwork, though, assaults even of this milder variety were not common events and it became quite clear at least from interviews with the staff that violence, or the threat of violence, was not a major source of anxiety for them. Approximately a third of the staff at Ashton and a third of the staff at Beechgrove were formally interviewed, in each case after their lessons had been observed on a number of occasions. Apart from the incidents involving the chemistry teacher at Beechgrove, at no time during the classroom observation was a teacher molested, assaulted or threatened with violence and in none of the sixty-seven formal interviews did a teacher suggest that the threat of violence affected his or her routine work. When the subject of violence in classrooms was broached during the interviews the general theme of the responses was that violence certainly might happen but it could generally be avoided unless the pupil concerned was ‘psychopathic’. In fact the spirit of the responses was captured by the comments of the language teacher at Beechgrove whose lessons were interrupted by the attacks on the chemistry teacher next door:

You see, there are some kids who really ought not to be here because they’re emotionally unbalanced. There’s not a lot you can do about them is there? I mean if they’re in the school and you’re stuck with them, if they’re going to do something dreadful like with Miss——who got stabbed, well … you can’t do much to prevent it. But I think you’ll find most of the teachers here would argue that when there’s trouble it’s usually the case that the teacher can sense when something’s brewing and can usually manage to calm the situation before the kid goes over the top – you know, get them out of the room or something. But then there are some teachers who just seem to aggravate the stroppy kids and then don’t know how to … kind of back down or defuse the situation.

The teachers I observed and interviewed, while they were aware of a slight risk of being assaulted, were actually more concerned with the mundane forms of control problem they had to deal with day in, day out, as a normal and predictable part of their job. It was in effect, disruptive behaviour rather than violent behaviour which they saw as the basic problem of classroom control.1 The reason for this was not that physical assaults were regarded in their own right as trivial but that they occurred quite rarely in comparison with the less extreme forms of disruption. This point emerged also from the research of Lawrence et al. (1977) in a London comprehensive school where they tried to gauge the extent of, and nature of, disruptive behaviour during two one-week periods; the first in November 1976, the second in February 1977. Thirty-six ...