![]()

1 Introduction1

Promoting sub-regional growth-oriented economic and trade policies towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals in selected Arab countries

Hanaa Kheir-El-Din and Fadle Naqib2

During the last decade, Arab economies, with the exception of those performing under conflict conditions,3 have shown some improvement in their macroeconomic indicators. Real GDP has experienced a growth rate in the range of 4–6 per cent, inflation has been kept at single digit and both internal and external balances seem to have been kept under control. At the same time Arab governments have implemented several measures, aimed at liberalizing trade, privatization of the public sector establishments and reforming financial markets. Nonetheless, Arab economies have not been able to attend to the most urgent needs of reducing unemployment and poverty. Presently, the Arab region has the highest unemployment rate among other regions in the world. This situation has raised serious questions regarding the trade–growth–employment–poverty nexus in the Arab countries, and raises a number of fundamental questions: to what extent has trade liberalization enhanced growth in the Arab economies; why have recent episodes of growth in most Arab countries been characterized as ‘jobless growth’; what is the relation between the process of growth and distribution of income in Arab countries; has recent experience of growth been associated with increasing inequality of income; what is the relationship between growth and poverty; are the majority of the poor excluded from the benefits of growth?

To answer these and other related questions, in 2008–10 UNCTAD conducted a research project entitled, ‘Promoting sub-regional growth-oriented economic and trade policies towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in selected Arab countries’. The project aimed at completing three tasks: first, to examine the relationship between trade, growth, employment, unemployment and poverty in the economies of Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) and Sudan; second, to utilize the findings to explore further the potential gains from regional integration in order to provide policy recommendations to promote a development-driven trade strategy aimed at reducing unemployment and poverty; and, third, to compile some important statistics on the pattern and structure of trade between the Arab countries and other trade partners that could anchor an evidence-based approach to the work of the researchers of this project. The current book is based on the findings of the studies conducted in this project.

This introductory chapter is divided into three sections. The first briefly summarizes the recent literature on the relationship between trade, growth, employment, unemployment and poverty. The main themes of this literature guided the five country studies. The second section presents a brief summary of the main findings of the five country studies. The third section summarizes the structure and the main findings of the quantitative study.

Trade, growth, employment, unemployment and poverty reduction: a brief review of literature

There are essentially three sources of economic growth in most countries: an increase in the availability of factors of production (labour and capital); more efficient allocation of factors of production across economic activities; and technological progress which brings about more productive uses of the existing factors of production. The first two sources have short-run transitional effects while the third brings about a higher long-term growth path. Economic theory maintains that opening a country to foreign trade and investment contributes to each of these three sources of growth. First, opening a country to trade is usually associated with free movement of factors of production, and that allows the economy to augment relatively scarce domestic resources and use part of its abundant factors elsewhere – where they earn a higher return. Second, trade allows the economy to allocate factors more efficiently as it can specialize in producing those goods and services in which it has comparative advantage. Third, trade allows for faster transfer of technology when the country imports new capital goods (machines and tools). Furthermore, competition in foreign markets creates the incentive for domestic firms to spend on research and development (R&D) to improve their competitive edge. To the extent that foreign direct investment (FDI) increases with trade, it allows for the transfer of ‘technical knowledge’ related to new efficient methods of organization and marketing.

It is recognized, however, that all the positive effects of international trade on growth will not materialize unless the country has a flexible economic structure capable of responding to potential trade opportunities. This requires mobile labour and capital that respond to market signals and can move quickly, at little adjustment cost, from one sector to another. This mobility usually leads to flexible wages and interest rates that respond to shifts in supply and demand, and allows the establishment of favourable terms of trade that enable participating countries to gain from trade. In poor, developing economies, capital and human resources cannot easily be transferred from one industry to another so as to take advantage of changes of supply and demand in international markets. Such transfer is a lengthy, costly and painful process. It is achieved more easily, however, at a time of growth as new investment and new entrants to the labour force are channelled to the industry whose product enjoys an increased demand in the foreign markets. In this regard, it is growth which allows the country to expand its trade and not the other way around. There is new evidence suggesting that during the early stages of development, trade liberalization is an outcome, not a prerequisite, of a successful growth strategy.4 However, at later stages of development, trade and growth may reinforce each other. A high growth rate of domestic output may serve to boost trade, and a high rate of growth of world trade may stimulate further expansion of domestic production.

These two views explain why the empirical evidence for the direction of causality between trade and growth is not conclusive. There are various empirical studies that overwhelmingly suggest that there is a strong positive relationship between international trade and economic growth. A good and well-known example of these studies is that of Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner (1995). They classified countries according to their openness to trade and then compared the growth performance in each classification. They argued that there is

a strong association between openness and growth, both within the group of developing and the group of developed countries. Within the group of developing countries, the open economies grew at 4.49 percent per year, and the closed economies grew at 0.69 percent per year. Within the group of developed countries, the open economies grew at 2.29 percent per year, and the closed economies grew at 0.47 percent per year.

(Sachs and Warner 1995: 35–6)

However, the validity of this conclusion has been questioned in the literature. Although ‘trade’ and ‘growth’ are said to be related, the above studies cannot say much on the direction of causality. Florax et al. (2002) have shown that a very large number of potential models could explain any observed economic behaviour; therefore, studies that examine just a small number of hypotheses cannot be said to robustly prove a specific model’s validity. A more direct criticism is related to the argument that trade liberalization policy is so closely correlated with many other economic policies. Therefore, it is impossible to differentiate between the effects of trade policy and those of other policies on growth. The argument strongly suggests that economic growth probably depends more on ‘those other policies’ than trade policy. Rodrik et al. (2002) showed that trade actually becomes an insignificant variable in a growth equation that includes explicit variables representing a number of institutional factors. Variables like the rule of law, property rights, human rights, patents and copyrights, a consistent and transparent legal system, and many other institutional variables, seem to be more important for growth than opening the borders to trade (Rodrik et al. 2002). Rigobon and Rodrik (2005) employed a new econometric method to compensate for simultaneous effects of many variables, and found that in the presence of other appropriate institutions, the effect of trade on growth is small.5

Growth, caused by trade or other factors, comes in different forms. During the last two decades, growth both in developing and developed countries has not led to substantial declines in unemployment. This ‘jobless growth’ phenomenon was very pronounced in all Arab economies during the 2000s. The average rate of growth for the region was higher than the world average, whereas the region’s average rate of unemployment was also higher than any other region in the world. Moreover, in the Arab world this phenomenon is associated with pronounced inequality, concentrating the fruits of growth in the hands of the elites and excluding the majority of the poor from the benefits. Consequently, these jobless episodes of growth are not sustainable as they are based primarily on fleeting increases in resource prices and have tended to create adverse incentives and discourage investments in physical capital, human capital and technology, leading to stagnation in the future. Equally important is the fact that such episodes of growth do not help the effort to foster development and alleviate poverty. Such effort requires that growth produces high-productivity and high-wage jobs for the unemployed and the poor. Sustained growth, therefore, requires the effective participation of the majority of citizens in a dynamic process directed by the state aimed at enabling the poor to improve their health and education so as to enable them to acquire assets, information and legal standing and allowing them to become part of the socio-political structure of the country. In other words, overcoming the problem of jobless growth in the Arab countries requires the adoption of a pro-poor growth strategy in which poor people benefit in absolute terms from the outcomes of economic growth and prosperity, resulting in poverty reduction.

This book aims at identifying first, the elements of the pro-poor growth strategy in each of the five selected economies and, second, the areas in which regional coordination and cooperation could reinforce this pro-poor growth strategy. As will be demonstrated in the remainder of the book, the findings of the five case studies all call for a deliberate, development-driven approach to regional coordination to act as a policy instrument aimed at tackling some of the region’s major economic problems. Regional integration should aim at rationalizing production at the regional level, creating employment opportunities, attracting higher levels of FDI, diversifying trade and industrial bases, raising living standards and reducing poverty.

Regional Arab trade integration

Given the mixed results of trade liberalization policies in reducing unemployment and poverty in the Arab region, and also in the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis which highlighted the risks associated with reliance on an international system of finance and commerce, a reconsideration of the potentials of regional trade integration is a timely exercise. The latter will not only allow for access to larger markets and demand bases closer to home, but also allows for taking advantage of regional pools of labour, capital and financial resources. Although the past experiences of trade and economic integration among Arab countries have been far from successful, this book explores the obstacles to a successful integration and discusses the policies required to remove them.

Several attempts have been made towards economic integration among many Arab countries. The League of Arab States (LAS) was established in 1945 to serve the political and economic purposes of the Arab region. Among the most important economic objectives of that institution was the establishment of the Arab Common Market. Since then, Arab governments negotiated many forms of regional trade agreements, ranging from bilateral treaties (to reduce tariffs on a limited number of goods) to ambitious programmes that could converge into an Arab Common Market. Examples of these include the 1953 treaty to organize transit trade in goods between member states; the 1964 agreement between Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Syria to establish an Arab common market; the 1981 agreement to facilitate and promote intra-Arab trade between member states; the short-lived Arab Cooperation Council, made up of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Yemen; and the Arab Maghreb Union, consisting of Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia. Most of these agreements have not been effective, and many were never fully implemented, resulting in limited intra-Arab trade compared to other regions.

The emergence of large trading blocs and regional trade integration agreements probably encouraged Arab countries to establish the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA)6 in February 1997. The liberalization of intra-Arab trade was scheduled to take place over a period of ten years, starting in 1998, mainly through phasing out tariffs. In addition, GAFTA’s executive programme called for the elimination of non-tariff barriers. A special committee was formed to track all forms of non-tariff barriers in member countries, with the objective of eliminating those barriers by the end of the transition period. In 2002, efforts were exerted to accelerate the tariff reduction process, and by January 2005 trade liberalization among GAFTA members was completed.

Below we offer an examination of the characteristics of Arab trade for the periods before and after the creation of GAFTA with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of GAFTA in promoting trade among its members. Before GAFTA, intra-Arab trade was around 8.3 per cent of total Arab exports in 1994; much lower than corresponding ratios for many regional blocs from both developed and developing countries. This ratio is estimated at 70 per cent for APEC, 62 per cent for the EU, 48 per cent for NAFTA and 18 per cent for MERCOSUR (Latin America) (UNCTAD 1997).7 During the pre-GAFTA period, the computed revealed comparative advantage (RCA) values suggest that a number of Arab countries seem to have export potential in a number of categories, with Morocco, Kuwait, Egypt and Tunisia standing out as better performers relative to the rest. These countries don’t just have RCA in many commodity groups, but consistently rank among countries with relatively high RCA values when compared with the rest. Although the results above indicate the existence of opportunities for enhancing the competitive positions of Arab countries and for increasing mutually beneficial trade among them, actual intra-Arab trade has not realized those benefits yet. The share of inter-Arab trade expanded in the last half of the 1980s but decreased during the early 1990s. In 1995, the share of inter-Arab trade in total Arab trade was 7.7 per cent – the same as that of 1984. The same holds for the share of inter-Arab exports (imports) in total Arab exports (imports), which remained relatively stagnant during 1984–95.

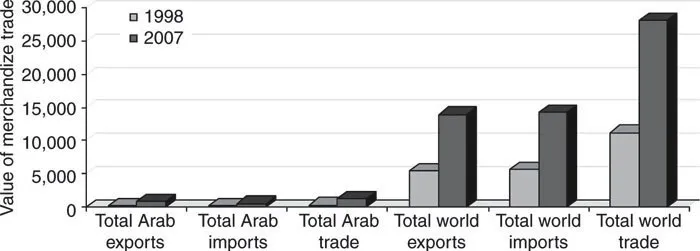

Upon signing GAFTA, although the process of tariff elimination was completed in 2005, a number of non-tariff and institutional barriers to trade still persist and prevent the full realization of gains from inter-Arab trade. Available data suggest that during 1998–2007, the value of total world trade increased by 152 per cent while that of Arab trade increased by nearly 326 per cent, more than twice the increase in world trade (see Figure 1.1). As a result, the share of Arab trade in world trade has increased from 2.7 per cent in 1998 to 4.6 per cent in 2007. This is explained by the 450 per cent increase in Arab exports (and the surge in oil prices) compared to a growth of 215 per cent of Arab imports, while world exports increased by 168 per cent compared to 150 per cent for world imports.

Figure 1.1 Arab and world merchandize trade (billion dollars), 1998 and 2007.

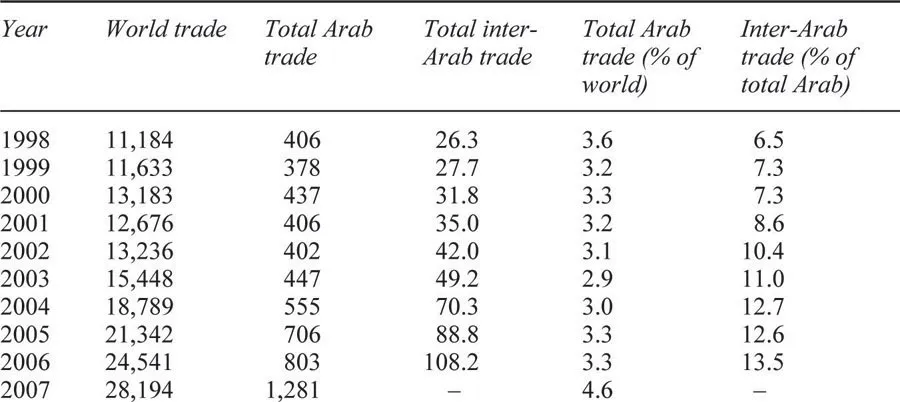

Table 1.1 reports total Arab trade in comparison to inter-Arab and world trade since 1998. The data reveal that global Arab trade has increased by 98 per cent over the period 1998–2007 (from US$406.2 billion in 1998 to US$802.8 billion in 2006) compared to a growth rate of 119 per cent for world trade. Inter-Arab trade has also exhibited a somewhat upward trend since 1998, increasing by 312 per cent during 1998–2006. Most important, while the share of global Arab trade in world trade has remained virtually constant at around 3 per cent since 1998, the share of inter-Arab trade in total Arab trade increased from 6.5 per cent in 1998 to 13.5 per cent in 2006.

Table 1.1 Total Arab trade, 1998–2007 (values in US$ billion)

Source: compiled and calculated from the Arab Monetary Fund and ITS (2003, 2008), available online at: http://www.amf.org.ae/publications.

The figures for intra-Arab trade are strikingly low when compared to other blocs such as MERCOSUR, where intra-member exports were 21 per cent of the region’s total exports in 2000, and 13 per cent in 2004. It should be noted that the picture is less gloomy when oil exports are excluded. Oil accounts for the greatest share of many Arab countries’ exports,8 and is largely exported to non-Arab countries. For these reasons, oil tends to bias the real magnitude of intra-Arab trade. When oil is excluded, the ratio of intra-Arab exports to total Arab exports average around 23 per cent during 1992–2004. Still, this ratio could improve significantly if barriers to trade are dismantled. Despite the elimination of tariffs between GAFTA members, intra-Arab trade is still hampered by a number of non-tariff obstacles that impede realizing the beneficial effects of trade liberalization and the full potentials of intra-Arab trade. More precisely, two non-trade barriers stand out as significant obstacles to the expansion of intra-GAFTA trade: cumbersome and bureaucratic institutional frameworks, and high transportation and communication costs, attributed partly to weak national and regional infrastructure.

Intra-Arab FDI trends

Global FDI inflows have increased rapidly during the last decade by a rate of 141 per cent, from US$705 billion in 1998 to US$1,697 billion in 2008. FDI inflows in Arab countries increased at the phenomenal rate of 630 per cent; 12 times faster than that of global FDI. It increased from US$5.6 billion in 1998 to US$96.9 billion in 2008. Despite this, FDI flows into the Arab countries have not exceeded 0.8 per cent of the global flows in 1998 and 6 per cent in 2008. FDI outflows from Arab countries also remained limited relative to other regions, with their share in global FDI outflows not exceeding 2.1 per cent in 2008. These figures suggest that not only the efforts made and the measures taken to create a better business environment and enha...