- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Iran-Iraq War (RLE Iran A)

About this book

The Iran-Iraq war broke out in September 1980. It brought death and suffering to hundreds of thousands of people on both sides and devastated the economies of both countries. It also increased international tensions by precipitating new alliances and rearrangement of forces in the already turbulent Middle East. The focus of this book is on the historical, economic and political dimensions of the war between Iraq and Iran. It examines many aspects of what proved to be a very complex conflict; including its long history, its present economic and political setting, the different responses to the war by outside parties and its regional and world implications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Iran-Iraq War (RLE Iran A) by M. EL-Azhary in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 |

INTRODUCTION |

M. S. El Azhary |

The Iran-Iraq war which broke out in September 1980 and which continues unabated in 1983 has brought death and suffering to hundreds of thousands of people on both sides, and it has devastated the economies of both countries. It has also increased international tension by precipitating new alliances and a rearrangement of forces in the already turbulent Middle East. And although the war, so far, has been limited to the two countries, it still has the potential danger of spreading the fighting at any moment to the rest of the oil-rich Gulf region, with incalculable results both for the states in the area and the world at large.

The focus of this book is on the historical, economic and political dimensions of the war between Iraq and Iran. It examines many aspects of what has proved to be a very complex conflict, including its long history, its present economic and political setting, the different responses to the war by outside parties and its regional and worldwide implications. But before embarking on an analysis of the intricacies of the conflict that are offered in the following articles, an overview of the main developments in the war during the past three years is in order.

In early 1979, after the Shi‘a Islamic revolution seized power in Iran, the new regime began exporting its brand of revolution to Iraq through a propaganda campaign aimed mainly at the Shi‘a community, which comprises more than half the Iraqi population, inciting it to revolt against the Sunni-dominated Baathist regime. Iranian leaders attacked the ideology of the Baath party as anti-Islamic, and Ayatollah Khomeini repeatedly called for the overthrow of the regime of Saddam Hussein, whom he called an enemy of Islam and Muslims. These and other calls by the Iranian leadership were accompanied by a terror campaign of bombing incidents and assassination attempts on Iraqi officials which were carried out by members of a right-wing Iranian guerrilla group.

The result was an atmosphere of fear and tension in Baghdad. The Iraqi government took the Iranian actions seriously and responded in a way that showed it was willing to go to war to put an end to them. First, Iraq countered with a propaganda campaign of its own. It denounced the ‘Persian magicians led by Khomeini’ and called for the overthrow of his regime. Radio Baghdad openly indulged in the racial stereotype that the Persians were dangerous and devious people and it appealed to the Arab world's dislike of al-’ajam — the non-Arab Muslims of the East.

Secondly, Baghdad armed and trained guerrillas who waged a sabotage campaign against Iranian oil installations. The Iraqi government also took reprisals by expelling tens of thousands of persons of Persian descent from southern Iraq. Thirdly, Iraq opened up its old territorial disputes with Iran which seemed to have been settled in the deal Iraq made with the Shah in 1975. Iraq called for a revision of the agreement on the demarcation of the border along the Shatt al-Arab; for a return to Arab ownership of the three islands in the Strait of Hormuz which the Shah seized in 1971; and, most dangerously of all, for the granting of autonomy to the minorities inside Iran. The granting of this last demand would have led to the fragmentation of the present Iranian empire, and this in turn might have led to a secessionist movement among the Arab community in the oil-rich province of Khuzistan in southern Iran.

In the meantime, sporadic skirmishes along the frontier became serious and more frequent. Throughout 1980 both sides were reporting tank, artillery and aircraft bombardment of their positions. But with Iran in the throes of revolutionary chaos, its armed forces appeared inferior to those of Iraq in material, morale, organization and discipline. So the Iraqi leadership was greatly tempted to grab the oilfields in southern Iran — which they tried to do when full-scale fighting erupted in September of the same year. They hoped that a quick victory on the battlefield, coupled with increasing their support to the anti-Khomeini forces inside Iran, would weaken further the regime in Tehran and thus force the Iranian government to accept Iraqi demands.

With this bold move Iraq was claiming the mantle of the dominant power in the Gulf region, the same role played by Iran under the Shah in the 1970s. But after a few weeks of fighting, the Iraqi armed forces had captured only a few hundred square miles of Iranian territory, which was not a sufficiently clear victory to bring about such grandiose results. The war soon developed into a stalemate, with the Iraqis prevented from advancing further or consolidating their hold on the occupied areas. This situation continued for months on end with no significant military action by either side.

To be sure, there was considerable damage done in these first few weeks of the war to the major towns in southern Iran, and to the oil installations of both sides. Iraq's oil exports from Khor al-Amaya and Mina al-Bakr at the head of the Gulf ceased because the loading terminals were badly damaged and the Syrians had closed one of the pipelines to the Mediterranean, thus limiting Iraq to the use of only one pipeline via Turkey. The Iranians, on the other hand, were able to restore their oil exports from Kharg island and the other terminals further down the Gulf. It is important to note, however, that after this initial damage to the oil installations of both countries, the two sides abided by an unwritten understanding that neither side would inflict further damage on the other's oil installations. Under these circumstances Iran has been able to pay for its own war effort, while Iraq has had to depend on Arab financial aid that has diminished in recent months.

In the spring of 1982 the Iranian armed forces regrouped and were able to dislodge and push back the Iraqis across the border. Now it was the turn of the Iranian leadership to try to implement a grandiose scheme of its own with the overall aim of regaining the dominant regional role Iran once had. In the following July Khomeini unleashed his army along the Shatt al-Arab in a huge invasion of Iraq. His objective was not just the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but the creation of an Iraqi Islamic republic modelled on that of Iran. Khomeini now was insisting that reparations for the damage from the war must come from Iraq. But the Iranian invasion failed, with the Iraqi armed forces performing better in defence of their homeland. Since then they have also succeeded in repulsing several other major Iranian offensives.

Soon the war reverted to a stalemate; it did not trigger a Shi‘a rebellion in southern Iraq, just as the earlier invasion of Khuzistan had failed to produce a liberation movement there. In fact, the war seems to have had the opposite effect: it has had the unintended result of increasing national pride and support for both regimes among their respective populations. Death and destruction, however, have been extensive, with the number of dead and casualties estimated in the hundreds of thousands. In economic terms, the devastation is incalculable on both sides: losses are estimated in tens of billions of dollars from the loss of oil revenues and the destruction of oil and other installations.

At the regional level, the war has not so far spilled into neighbouring states, nor has it obstructed access to oil from the Gulf; both parties have adhered to their declared desire of keeping the Strait of Hormuz open to shipping. Moreover, the United States has dispatched the AWACS (Airborne Warning and Control System) reconnaissance planes to Saudi Arabia to deter Iran from widening the war. In this respect, Iraq has been viewed as the less dangerous of the two combatants, considering its improved relations in recent years with Saudi Arabia, the smaller Gulf States, Jordan and Egypt, all of which have sided with Iraq in the war and given it financial as well as logistical support. Iraq has also improved its relations with the West generally, and increased her arms purchases from France.

Furthermore, Iraq has split from the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front, whose members — Syria, Libya, South Yemen (PDRY) and Algeria — have sided with Iran in the war; thus a new divisive factor has been introduced into inter-Arab politics. Consequently, this division in Arab ranks has produced the negative effect of shifting Arab concerns away from the Arab-Israeli conflict; it also encouraged the Reagan administration to neglect this problem and feel no urgency to reactivate the search for peace until disaster struck in Lebanon in the summer of 1982. From Lebanese and Palestinian perspectives, it was this distraction and neglect that gave Israel a free hand on such an unprecedented scale, bringing calamitous results for both peoples.

The two superpowers have found it advantageous to stay neutral towards the war between Iraq and Iran. Although their stakes in the conflict remain high, both lack leverage to influence the course of the conflict. Yet both have expressed concern, because it is in their interest to avoid the danger of the fragmentation or dismemberment of either side.

The articles in this book cover four broad aspects of the Shatt al-Arab dispute, each of which contributes to an overall understanding of the present conflict. First, in a historical survey of the long antagonism between the two sides and the strategic importance of the Shatt al-Arab for them both, Peter Hünseler (Chapter 2: The Historical Antecedents of the Shatt al-Arab Dispute) shows that for centuries both countries have made claims and counterclaims on each other's territory, supporting their respective positions by ethnic, political or religious arguments. Mustafa al-Najjar and Najdat Fathi Safwat (Chapter 3: Arab Sovereignty over the Shatt al-Arab during the Ka'bide Period) chronicle the history of the Arab dynasty of the Bani Ka'b, who in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries established their domain east of the Shatt al-Arab in Arabistan and imposed Arab sovereignty over the Shatt.

Second, the economic and political setting of the present conflict is examined in three articles. David Long (Chapter 4: Oil and the Iran-Iraq War) shows how the shift to alternative sources of energy, in progress since the 1973–4 oil price rise, combined with market forces to moderate the impact of the war on the worldwide demand for oil. Long assesses the devastating impact of the war on the Iraqi and Iranian oil sectors. John Townsend (Chapter 5: Economic and Political Implications of the War: the Economic Consequences for the Participants) looks at the effects of the war on the major economic activities of both countries, particularly foreign trade, economic development programmes and manpower. Basil al-Bustany (Chapter 6: Development Strategy in Iraq and the War Effort: the Dynamics of Challenge) focuses mainly on the impact of the war on the five-year plan of 1981–5; he goes into greater detail about how the development programmes are being implemented so far. Although al-Bustany's assessment is written from a different perspective than that of Townsend, the two are not necessarily incompatible.

Third, in the international field, the external attitudes to the Iran-Iraq war and its regional and worldwide implications are examined in three articles. G. H. Jansen (Chapter 7: The Attitudes of the Arab Governments towards the Gulf War) explains the varied reasons behind the lack of support for Iraq from most Arab states. M. S. El Azhary (Chapter 8: The Attitudes of the Superpowers towards the Gulf War) analyses the positions taken by both superpowers towards the conflict in the context of their bilateral relations with both Iraq and Iran. From a different perspective, and with a wider scope than in the two previous articles, John Duke Anthony (Chapter 9: Regional and Worldwide Implications of the Gulf War) evaluates the concerns of the outside world at the regional and global levels.

Fourth, the prospects for a peaceful settlement of the Gulf war are assessed in the final article by Glen Balfour-Paul (Chapter 10: The Prospects for Peace) in the light of his analysis of the real issues in dispute between the two combatants. This also sheds some light on the failure of all the attempts at mediation made so far in this conflict.

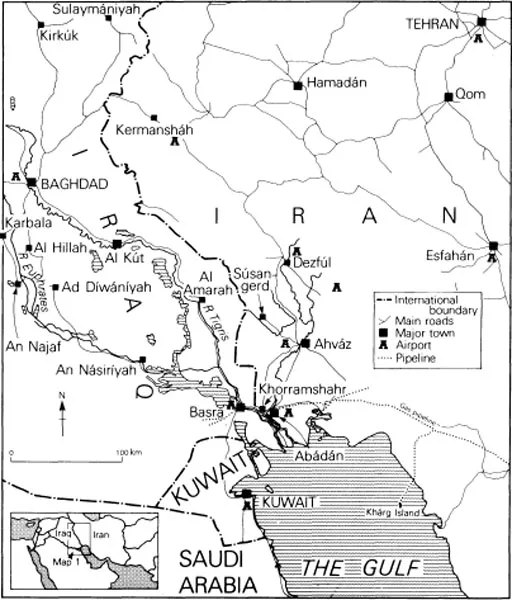

Map 1.1: International Boundary Line Between Iraq and Iran

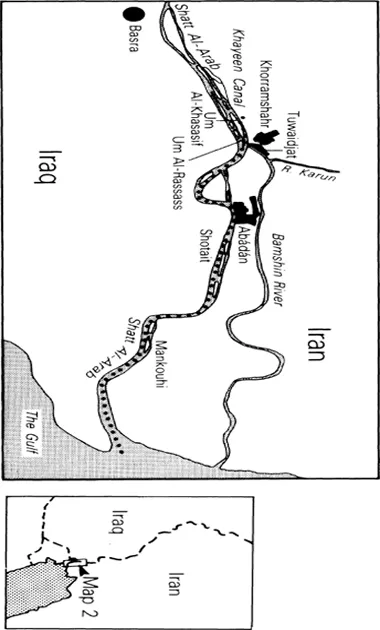

Map 1.2: The Shatt al-Arab Frontier, Algiers Agreement (6 March 1975)

2 | THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF THE |

Peter Hünseler |

The Shatt al-Arab Dispute in the Overall Context of Persian-Arab Antagonism

Unlike the course taken by other peoples who came under subjection in the Arab conquests of the seventh century, Persia succeeded in maintaining its national character against the invaders. When, in AD 636, the Persian Sassanids were defeated at the Battle of Qadisiya near Hira by the Arab armies of General Sa'd bin Abi Waqqas and the empire itself came to an end with the Battle of Nihawand in 642, its population, conscious of the state's territorial integrity and cultural continuity, converted to Islam. The conquering Arabs and the peoples they subjected considered Arabism and Islam a unity; the Persian culture, however, ‘though overlaid by Islam, could not be suppressed’.1

A key principle which has permeated Persian history since the Arab conquests, and strongly influenced its current social and political life, is that of a juxtaposition of Persia and Islam. This principle has arisen out of the Zoroastrian view of a state which tends towards a secularly-legitimized kingship, the survival of the Persian language (albeit soon written in Arabic script) and the proud awareness of a distinct Persian history. Within only two centuries, the Sunni-Arab caliphate of the Abbasids had come to find Persian literature attractive. Real power was seized, time and again, by the Persian dynasties in the Abbasid caliphate. Between 954 and 1055 — for over a century — the Buyid dynasty managed to control political events in Iraq and western Persia and to restrict the Abbasid caliphs to a purely religious role. ‘Thus the history of the Buyids in Iraq can bee understood as a struggle between Arabism and Persianism’.2

The adoption of Shi'ism as the state religion in Persia by the Safavids early in the sixteenth century constituted the zenith of Persia's delimitation from its Arab neighbours, while remaining within the context of Islam. For the first time in the history of Islam, Shi'ism thereby established itself in a state, thus fragmenting, in a way previously unknown, the unity of the Islamic world. The Safavid kings viewed themselves primarily as secular rulers and left religious leadership to the theologians. The Shi‘a clergy subsequently became unwilling to relinquish the powerful position they had acquired under the Safavids. Especially under the early Qajar rulers, land and money had been lavished upon them, gaining for their leaders economic independence from the monarchy and a steady growth of influence in Persian politics. No comparable development had taken place in the neighbouring Sunni Arab states.

A new dimension had therefore been added to the original contradiction between Arab and Persian nationalism: the Sunni-Shi‘a antagonism. In that context, adherence to divergent branches of Islam proved less significant than the differing degree of influence exerted by religion on the formation and appreciation of politics and state power. That condition still prevails today, particularly in those states in which an Arab population is divided into Sunnis and Shi‘a.

The leaders of the Shi‘a clergy in the Arab states (Iraq, Bahrain) could not attain an exclusive social position comparable to that in Persia, where the Shi‘a acquired a national religious importance. Hence these Shi‘a clerics found themselves exposed to a dual conflict of loyalty: on the one hand, they preached Shi'ism in a state not homogenously Shi‘a and were thus drawn into the historic antagonism between Sunni and Shi‘a; on the other, as Arab Shi‘a they were suspected by their Arab rulers of succumbing to non-Arab (in other words, Persian) influence. Only too often they were perceived by their Arab compatriots as represen...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- TABLES AND MAPS

- PREFACE

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF THE SHATT AL-ARAB DISPUTE

- 3. ARAB SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE SHATT AL-ARAB DURING THE KA‘BIDE PERIOD

- 4. OIL AND THE IRAN-IRAQ WAR

- 5. ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE WAR: THE ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES FOR THE PARTICIPANTS

- 6. DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY IN IRAQ AND THE WAR EFFORT: THE DYNAMICS OF CHALLENGE

- 7. THE ATTITUDES OF THE ARAB GOVERNMENTS TOWARDS THE GULF WAR

- 8. THE ATTITUDES OF THE SUPERPOWERS TOWARDS THE GULF WAR

- 9. REGIONAL AND WORLDWIDE IMPLICATIONS OF THE GULF WAR

- 10. THE PROSPECTS FOR PEACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX