![]()

1

Emotion As Action

The imperative to investigate emotions as cultural phenomena results from theoretical developments in recent decades. Critiques of the overvaluation of reason in Western culture and explorations of the body as culturally constructed and always-changing ways of being demand similar analyses of the vast category of experience identified as ‘emotion.’ Poststructuralism has undermined the humanist subject, replacing the individual who preexists the world he or she was said to create with a subject constructed in culture, through a process in which the subject and culture are mutually constituting. Such a reevaluation necessitates further examination of other aspects of existence, like the emotions, long considered biological or psychological properties of the individual. Contemporary interest in subjectivity and identity, and the search for explanations of how social categories are simultaneously entrenched and dynamic—the means by which they become fixed yet alter—also demands a better understanding of the participation of emotions in these processes.

In this chapter I assess a single but vital area of inquiry that has provided impetus to the development of a cultural emotions studies: feminism and gender theory. Due to the long-standing historical connection between women and emotions, second-wave feminism as a social and political movement and feminist studies as a theoretical enterprise began to engage with emotions, although often in implicit or indirect ways. Examples include elaborating and arguing the social, economic, and political ramifications of ‘the personal,’ and sorting through the consequences of women’s role as dominant caretakers in relationships. Gender provides a useful background in explaining how and why we have arrived at the pressing need for a cultural understanding of emotions, and it sets in motion some of the shapes such a field of inquiry might assume.

More specifically, I examine critical accounts of the 1980s television detective drama Cagney and Lacey, which featured two women as its central characters and conspicuously addressed issues brought to the fore by the second women’s movement and feminist studies. Utilizing scholarly analyses of the series, principally Julie D’Acci’s 1994 book, Defining Women: Television and the Case of Cagney and Lacey, I explore some of the ways a cultural approach to emotions opens up new possibilities for both emotion studies and media studies. My purpose is to focus on the junctures among identity, genre, and emotion as Cagney and Lacey, and the critical discussions surrounding it, worked to reconstitute notions of gender, characterizations of police detectives, and the dynamics of emotion as a form of narrative action.

Defining Women is a highly respected analysis and one of the earliest attempts to integrate the multiple, complex factors of institutions, texts, and audiences. Here, I use its arguments as representative of assumptions operative in contemporaneous film and television studies that tended to sideline emotion as a productive theoretical category or valuable critical concept. In separating emotions from the political and social, as D’Acci and others often did, we lose the ability to consider how emotions function in the portrayal of public events and in the development of cultural identities. Rethinking the role of emotions in film and television texts allows us to break from models that view emotions, first, as solely or primarily aspects of women’s genres and, second, as traits associated largely with women. Investigation of the intricate and extensive ways emotions function in narrative leads to the recognition that they do much more than lock women’s genres into oppressive femininity or somehow allow masculine genres to evade feelings altogether.

ASSIGNING EMOTION

In an important essay, first published in 1989, philosopher Alison Jaggar outlines a series of conceptual progressions leading to the modern view of emotion. From the seventeenth century on, reason was believed responsible for the production of objective, scientific, and universal understandings of reality. This “modern redefinition of rationality required a corresponding reconceptualization of emotion” (2009, 51). In order to obtain objectively accurate accounts of both the human and natural worlds, rationality needed to be dispassionate: capable of withstanding subjective impurities that skewed or tainted systematically logical results.

Accordingly, emotions were demarcated as the location of subjectivity and bias, thereby becoming the harmful antitheses of reason. “This was achieved by portraying emotions as nonrational and often irrational urges that regularly swept the body, rather as a storm sweeps the land” (51). In structuring emotion as a distinct realm infiltrated with subjectivity and irrationality, reason could be preserved as its uncontaminated dichotomy— the site of authentic detachment and disinterest.

Emotions not only have been distinguished from reason in a way that marginalizes them, but emotion and reason are placed in a hierarchy in which their relative value is differently assessed. Emotion is considered the more harmful because it is the more unpredictable of the two while reason, associated with scientific thought and universal truths, becomes excessively valorized.

Sharply dichotomized, emotion and reason are then linked to other qualities, which, in turn, become oppositional. Rationality is allied “with the mental, the cultural, the universal, the public, and the male, whereas emotion has been associated with the irrational, the natural, the particular, the private, and, of course, the female” (50). Concerned particularly with gendered implications, Jaggar argues that “a differential assignment of reason and emotion,” in which the former is allocated to masculinity and the latter designated feminine, was applied despite the lack of evidence that “the thoughts and actions of women are more influenced by emotion than the thoughts and actions of men” (59). Instead, the difference is that in the specific assignment of social responsibility for emotions women have become more adept at their recognition and management both in themselves and in others (64). It is the cultural assignment of emotion or reason that accounts for discrepancies, not the inherently biological or psychological propensities of women and people of color, who are “permitted and even required to express emotion more openly” (59).

The implications of the differential assignment of emotion and reason expand. Gendered and racially based emotional assignments identify women and people of color as socially inferior while reason is aligned with, and used to justify, political and social dominance. One of the functions of the valorization of reason is to “bolster the epistemic authority of currently dominant groups,” while discrediting “the observations and claims” of subordinate groups (59). Because reason and emotion are perceived in terms of a hierarchy, those allied with reason are more highly valorized than those linked to emotion. Masculinity takes on the cultural associations of reason—objectivity, veracity, legitimacy—while femininity is diminished through its affiliation with partiality and unpredictability. The political and social judgments of those aligned with reason are then accepted, by definition, as more accurate and truthful while the observations and claims of those linked with emotion are inescapably irrational and flawed. Therefore, those cultural bodies correlated with reason rightly take up their social, economic, and political positions of dominance.1

Further, the more “forcefully and vehemently” subordinate groups articulate their differing judgments, “the more emotional they appear and so the more easily discredited,” thus “vindicating the silencing” of social categories “who are defined culturally as the bearers of emotion” (59–60). The stronger the objections against the opinions and actions of those in power, the more likely such objections will only confirm the perceived justice of a system of dominance and subordination purportedly based on a meritocracy of reason over emotion.

I use Jaggar’s analysis of the historical relationship between reason and emotion to exemplify some of the ways that both rationality and physical or bodily action, associated with male genres, have been placed in a hierarchy and valorized at the expense of emotions, linked to women and women’s genres.

INTERACTION

Writing in the late 1980s, Jaggar addresses culturally familiar suppositions about women as emotive beings, some of the same stereotypes grappled with in Cagney and Lacey. First appearing as a two-hour made-for-television movie in 1981, Cagney and Lacey continued as a weekly series from 1982 until its ultimate cancellation in 1988.

In her classic 1994 study of the series, Defining Women: Television and the Case of Cagney and Lacey, D’Acci seeks to identify the multiple meanings of ‘woman’—“as a notion produced in language and discourse,” ‘women’—“as historical human beings,” and ‘femininity’—as the positions available for woman and women to take up at specific historical and cultural moments (3). In the instance of Cagney and Lacey, this would include changing notions of the three terms—woman, women, femininity—resulting from the women’s movement that began in the 1960s as well as the subsequent backlash to it that D’Acci argues occurs in the 1980s.

D’Acci’s concern, then, is how specific discursive meanings become possible or even culturally ascendant, under what conditions, and due to which factors. In order to explore this topic, D’Acci specifically examines how such meanings were constructed and contested by multifaceted aspects of the institutions, texts, and audiences surrounding Cagney and Lacey, all of which participated in establishing, and altering, the program’s meanings.

The focus of D’Acci’s study is primarily political, in two senses. First, if gender is discursively and culturally constructed, then it becomes possible to intervene in and influence popular or predominant perceptions of woman, women, and femininity. D’Acci investigates the ways in which Cagney and Lacey succeeded, or failed, in this attempt (and, of course, her analysis serves as another level of intervention).

Second, as D’Acci explains, she was originally drawn to analyzing the series because it was “the first dramatic program in [U.S.] TV history to star two women in the leading roles,” an antidote to the complete absence of women ‘buddy’ films, for instance (5, 16–17). More specifically, the representation of its female lead characters, and the circumstances of their existence as detectives within “the traditional police genre,” explicitly included issues raised by the liberal women’s movement (5, 6). Thus, the show’s depiction of social and political concerns, such as sexual discrimination or harassment in the workplace, the difficulties involved in juggling careers and personal lives, spousal abuse and police attitudes about it, breast cancer and the medical profession’s responses to it, take up a central place in both the series and D’Acci’s study.

Unlike Jaggar, D’Acci does not overtly address the representation of emotions (although she cites from viewer letters that do). However, she does analyze, in detail, aspects of Christine Cagney’s and Mary Beth Lacey’s personal lives and, in particular, the relationship between the two women.2 Cagney’s and Lacey’s personal lives and the relationship they forge as partners and friends are central to the show’s pleasures for its viewers. Additionally, the personal and relationship aspects play a significant role in enabling the series to incorporate issues raised by the women’s movement.

D’Acci describes the friendship between Cagney and Lacey as “unquestionably the heart of the movie and series,” motivating and structuring their narratives, and serving as “the terrain on which many of the negotiations involving woman, women, and femininity found expression” (182). The friendship aids feminist goals because the bond between the two main characters is based on their mutual support as they deal with issues that are part of the contemporary construction of “women,” such as Cagney’s date rape and Lacey’s breast cancer, and, especially, their solidarity in contending with a masculine workplace and society (189). D’Acci argues that the depiction of the central relationship can be interpreted as feminist because it “allowed the notion that even women’s friendship was constructed in relation to historical conditions and events” (182), that is, not just as the two characters’ individual problems but as stand-ins for the social challenges facing all women.

One important means by which the relationship functions as the terrain upon which contemporary concepts of women may be struggled over has to do with the notable differences between the two characters. For instance, although Lacey is the more politically liberal and sympathetic to feminism, she is also the more traditional wife and mother. Cagney is more politically conservative and less empathetic to others, but she is far more ambitious in terms of her career and, because she questions the validity of the institution of marriage, chooses to stay single. Within the restricted parameters of white heterosexuality, the contradictions within each character, and the differing position each takes up on almost every issue that arises, permit the nuances and complexities of the particular problem to be disclosed and heatedly disputed.

In D’Acci’s analysis, the relationship between Cagney and Lacey derives from various forms of conversation: banter, sarcasm, arguments, competitive exchanges, jokes, and personal confessions.

First and foremost, Cagney and Lacey talked. They talked about how their police cases affected them and about their lives outside of work. (183)

The favored location for their most intimate conversations is the station’s women’s washroom. It was referred to as “the Jane” in series scripts and, emphasizing the aspect of talk, as the need for a ‘conference’ on the part of the characters (“Conference, Mary Beth” or “Conference, Christine”). D’Acci finds the women’s restroom a fitting place for Cagney and Lacey to hold their most intimate conversations because it is a “private space” existing on the “margins of the institution,” in the literal sense of in the recesses of the police station, as well as metaphorically for women who operate at the edges of a traditionally male profession and, by extension, for all women relegated to the margins of society (187, 185–186). Yet it is worth remembering that if the Jane scenes function symbolically at the margins, in narrative terms they exist squarely at the center of the series. Further, the reason that Cagney and Lacey have the washroom to themselves is due to the lack of other women on the force, a public and sociopolitical concern, not a function of it being an inherently “private space.” Otherwise, it would be difficult to see why the common motif of two male detectives talking about relationships in a locker room wouldn’t also be considered personal conversations occurring in a private venue.

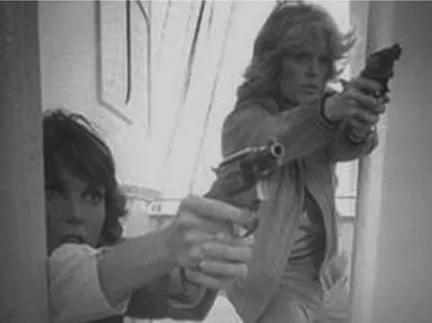

Figure 1.1 Cagney and Lacey—partners …

D’Acci reasons that the ‘talkiness’ of Cagney and Lacey enables its narratives to represent many gender issues productively, in their deserved complexity, far more than is the norm for police dramas. Indeed, she recognizes the focus on their relationship and the amount of attention devoted to conversation, “as a surefire way of distinguishing Cagney and Lacey from male cop shows” (184). However, the same elements that differentiate Cagney and Lacey from masculine examples of the genre are also the sites of the limitations she perceives in the series, precisely in its feminist impact or gendered implications.

Figure 1.3 A conference in ‘the Jane’ on Cagney and Lacey.

First, she contrasts the talk of Cagney and Lacey to the traditional action of police dramas. In this comparison, talk is a form of emotional exchange while action is physical or bodily endeavor. She characterizes these, respectively, as ‘interaction’ and ‘action’: “As the series progressed, the ‘action’ components of the scripts became almost totally subservient to the ‘interaction’ components” (223). Second, she identifies talk, especially when it is dedicated to how the characters are affected, as a...