eBook - ePub

Education and the Working Class (RLE Edu L Sociology of Education)

- 4 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Education and the Working Class (RLE Edu L Sociology of Education)

About this book

When first published this book had a significant influence on the campaign for comprehensive schools and it spoke to generations of working-class students who were either deterred by the class barriers erected by selective schools and elite universities, or, having broken through them to gain university entry, found themselves at sea. The authors admit at the end of the book they have raised and failed to answer many questions, and in spite of the disappearance of the majority of grammar schools, many of those questions still remain unanswered.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Education and the Working Class (RLE Edu L Sociology of Education) by Brian Jackson,Dennis Marsden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

THIS book is about working-class children turning into middle-class citizens. It’s a tangled picture, and the voices weave their own pattern of delight, snobbery, frustration and love:

‘When our Stanley was a lad, I’ll tell you what – I wanted him to go into politics. Aye, more than anything, I wanted our Stanley to be Prime Minister, to be Labour’s first Prime Minister.’

‘Up we’d go into the yard and climb up to the windows, and we’d push our faces right up – a right scruffy lot we were – and stare at all these brownies and cubs inside with all bright, clean uniforms. They seemed so pretty, so clean. I always hated them.’ ‘It’s funny, but when it came to that exam to go to grammar school, I don’t think I properly realized what it was. I might have said “good luck” when he set off, but I didn’t seem to be bothered about it.’

‘Christ, no. I didn’t like the College. Too fast, they just got me there and they crammed my nut from the moment I arrived. That school doesn’t turn out human beings, it turns out people to read and write, that’s all.’

‘He used to send me notes about how our Allan shouldn’t go to Speech Day in his trilby hat when he was still a schoolboy. Why, there was nowt wrong with it. He looked daft with a little cap perched on his head.’

‘Now when your child is coming along and going to grammar school, you begin to get excited, you begin to be interested, and you want to know more things. That’s how it was with us. It was a wonderful thing for us our children learning all these new things.’

‘Don’t come talking to me about Huddersfield bloody education, it’s time that the bloody ratepayers went and shook them buggers up. We’re good citizens, aren’t we? We might be poor folk around this way, but we’ve as much bloody right as any other buggers in this bloody town to get the job done properly.’ ‘And there he was right on the edge of the crowd, by the railings, and I went up to him and congratulated him, and gave him a pound that his Aunt Lilly had sent him. I said, “I’m sorry I can’t give you any money, love,” and he said, “Never mind about that, Mam, you’ve given me help and confidence and ...”; it was three words he said . . . ‘aren’t I silly?’ ‘ ‘I like to go back and I still like visiting. I like to go round and hear relations talking about themselves . . . but I’m not sure . . . I’m not sure whether it’s quite the same interest as I used to have, or if I regard them more as . . . well . . . specimens.’

We didn’t really know why we wrote this book until we’d finished it. One reason – ‘out there’ – was that the dominating class in Britain still underrates the colossal waste of talent in working-class children. We still hear fierce argument that very few more children are capable of grammar school education, or G.C.E., or university entrance, or first-class honours degree standard. The hard evidence suggests that if we could open education as freely to working-class children as we have done to middle-class ones, we would double – and double again – our highly talented and highly educated groups. This was meant to be a small contribution to that long debate.

But that wasn’t quite our reason. In the search for equality through education there is a peculiar blockage. Much has been gained – compulsory schooling, free schooling, secondary schooling for all. But was it altogether worth it? Did the child gain or lose in winning through to middle-class life, and growing away from working-class origins? We had no fixed views on this. But we felt this note of scepticism, obscured by the grand promise of building the open road to equality and varied excellence. This book was our attempt to find out where was gain and where was loss. We hoped it would help to ask whether, in a world of contradictions, the working-class child must or must not accept the present price of access to high culture, to intellectual satisfactions and to material well-being for himself and his children.

Harder still to define was the personal reason. In this report we are deliberately mapping out a stretch of life, an initiatory experience, through which we lived ourselves. And with this survey we took our bearings.

Hence the method. We gathered a sample of ninety working-class children. Two of the names on that sample are Brian Jackson and Dennis Marsden. In this report we track the fortunes of the other eighty-eight – the ones we saw. But the reader, standing further back than we ever can, perceives the full ninety.

Probably this has been done somewhere before. We didn’t know any example and that must excuse any shakiness in what, to us, was a piloting venture. There were two academic reasons why we followed the pilot methods we did. First of all, sociology is often bedevilled by a somewhat naïve view of ‘objectivity’. As human beings studying human groups, all sociologists cannot but experience many complex forms of involvement. The very choice of any research project in sociology inevitably presumes an act of judgement in which personal values and personal history play their own – perhaps deep-hidden – role. The true science lies in recognizing this, not in avoiding the terrain where involvement is most perceptible. We jumped in at the deep end, tried to be methodical, tried to be honest, and tried to leave the reader free to redeploy the evidence.

But ‘methodical’ hides a familiar battlefield. More and more human knowledge is divided up into separate disciplines. Yet the richest land may fall betwixt and between. Sociology is very anxious to establish itself as an academic discipline in our ever-conservative universities, and very rightly its keenest energies may go into tighter and tighter definition of measurable variables and theoretic bases. But, unfortunately, out of this anxiety comes restriction, and you hear of over-academic sociologists dismissing a vast amount of non-theoretical work as ‘not proper sociology’. So much for Charles Booth, Beatrice Webb and Peter Townsend! Even more extreme, it’s quite common to meet sociologists who put aside the work of the novelists as merely entertainment, and have no conception at all of what the great masters of prose fiction have yielded to our central store of knowledge about the workings of society.

On the other side there are the literary academics who know well enough what subtle tools lie at the command of a Dickens, a Conrad or a Lawrence. But perceiving these, they ignore (’social engineering’) the brave, raw equipment that sociology has built up, which can give us a kind of knowledge man has never had before. It is a sad academic clash (there are others like it) which, no doubt, will be with us a long time.

So, out of this, we went for the middle territory. Where we can, we measure. But much of this survey is in the form of quotation, scene, incident. When we use this material we are not ‘illustrating’ the figures, or decorating a theme. The speaking voices are as basic as the tables. They are the theme. And in them lie the truths, often perhaps overlooked or missed by us, that make ‘education and the working class’ a subject that matters.

HUDDERSFIELD

Huddersfield is a rich city. It claims to have more Rolls-Royces per head than any other place on earth. Its unemployment problem is slight, and prosperity has flowed here in easy tides since the 1930s. It enjoys a protective variety of industries, being neither an engineering centre, nor a woollen city, nor a cotton town, nor a brewing capital. It is all these at once, and much more besides. Such distribution of work and wealth guards it from the lesser trade cycles that trouble neighbouring cities. It has its poor, its aged, its crippled, its sick, its unlucky; but these are not easily seen, and their presence, if not forgotten, is obscured by the general buoyancy.

The city has a population of 130,000. In 1800 it was just touching 7,000 – for Huddersfield is one of the new cities of England, the cities bred out of the industrial revolution. Its population spiral follows Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham. By 1820 that 7,000 had nearly doubled into 13,000; by 1840 it had almost doubled again to 25,000. By 1890 it had leapt to over 90,000. The railway had arrived; and after the great new railway station came the city’s major public buildings – the new parish church, the post office of 1875, the town hall of 1879. The local historians trace all this back to the medieval hamlet, or the Roman station. They point to Brigantine settlements on the surrounding hillsides, or Saxon ruins along one of the far valleys. They drag up shields and coats of arms, and all the rich drapery of the medieval past. But Huddersfield as a society has no such history. The Romans and the Normans merely travelled over the same stretch of earth, and handed nothing down. Huddersfield begins with the industrial revolution.

It sucked in the population of the surrounding countryside, and with them something of their culture. But the ‘culture’ of Huddersfield is the submerged culture of the industrial working class. It is now settled and stylized into a pattern of living, but it was bred in the long working hours of the mills, the rapid spread of overcrowded streets, the tangles of the master-man relationship, the personal cycle of poverty (childhood/marriage/ age) crossing the national waves of work or hunger. Such a style of living, and fashioned by such conditions, radiates today from the close centres of family life into that whole web of ties – kinship, friendship, the shared childhood or working life, the formal groupings of club, band, choir, union, chapel – all the many strands of ‘neighbourhood’ that reach out to attain ‘community’. The expectations, dues, refusals, irritations, rights and assurances that family and neighbourhood arouse and inherit play all through this report. For the working-class culture of Huddersfield (an area with over 70 working men’s clubs) is by no means the same as the national middle-class culture, some of whose facets are reflected back by the wireless, the press, the very books in the public library. We are not concerned to choose or judge between the two cultures, merely to remark the difference. For it is a question of difference, and this report finds itself continually dipping into discussion or conflict where well-meaning people on both sides are fighting out battles between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Huddersfield has its prosperous middle class. Or, rather, it has two middle classes. The first is national, metropolitan in interest, mobile, privately educated. Such are the senior civil servants, doctors, executives, who stay a while and pass through the city; or who belong as natives here, but ‘belong’ elsewhere too. And then there is that other middle class, very local and rooted, of the self-made businessmen, works officials, schoolmasters clinging to their home town. Such a class is part of ‘them’ but in some situations can merge for a while with ‘us’. This native, rather than national, middle class has been there from earliest days; drawing its money from the work of the men, but nonetheless close to them. There is a report by a hand-loom commissioner of 1839 that ‘... the men of Huddersfield were constantly in their mills and taking their meals at the same hours as their work-people, but the clothiers of Gloucester were indulging in the habits and mixing with the gentle blood of the land’. It is just this native middle class we present here.

Huddersfield is one of the spread of cities that cover south Lancashire and Yorkshire, with wastes of moorland between them. Only a short journey, over the roads that curl through the moors, takes you into the opposing county. And on almost every side Huddersfield is hemmed in by other industrial centres, though yet with decent intervals of empty fields between. In only one direction have the open gaps been choked by creeping suburbia. We will not here describe the details of the city’s streets and homes; such as matter will emerge as the survey gathers way. But the city’s confidence in terms of work, of money, of pleasure, can be caught in a rapid glance. It is the confidence of the new industrial town after twenty years without recession. A correspondent who recently visited it felt that it was like nothing so much as the boom towns of the middle west; and touching on its satisfactions wrote, ‘A sanctuary lamp in the parish church was placed there, by members of the local Home Guard, so a plaque blandly informs us, in memory of their own devoted service.’ Had he consulted the latest guide book he would also have observed that Huddersfield, though on the Oxford Atlas some eighty miles north of Birmingham, officially considers that ‘it may be said to be almost in the centre of England’.

EDUCATION IN HUDDERSFIELD

Huddersfield then is prosperous, provincial, and confident in its material world. And as the word ‘prosperous’ covers over obscure pockets and cycles of hardship, so does the word ‘provincial’ merely catch the surface quality of a developed style of living within different social groups. Its material complacency, which is so easy to detect and illustrate, is also the more relaxed, if more normal, side of its essential citizenship. For Huddersfield has had other desires, and amongst them all we are now going to confine ourselves to education. This report illustrates how different social groups – the working class, the local middle class – with ‘cultural’ strengths of their own, reach out for the central culture of our society as it is inherited and transmitted by universities, colleges and schools. We are concerned only with state education – and here a competitive situation arises.

A quick historical glance is useful, serving to fit Huddersfield within the common framework, and to introduce its four grammar schools. In 1838 the Nonconformist manufacturers, whose entry to Oxford and Cambridge was still barred by the Anglican ‘gentle blood of the land’, founded Marburton College for the education of their sons and daughters. It offered a liberal training in the classics on traditional lines, supported by study in mathematics and the natural sciences. In 1894 the school was taken over by the city, and later divided into the two ‘first-class’ grammar schools – Ash Grange High School for Girls and Marburton College for Boys. Characteristically, their most distinguished pupil in the early part of the century was one of the great leaders of the Liberal party. Meanwhile, a small and shaky grammar school foundation from the seventeenth century still existed in a nearby village and, as the town grew and flourished, this school (Abbeyford Grammar) struggled into new life. A fourth grammar school, Thorpe Manor, was founded early in this century to handle the expanding numbers. These briefly are the origins of Huddersfield’s grammar schools: founded, and often staffed, by the local middle class for the children of that class. Their ultimate model is the public schools and the eldest grammar foundations. To our own time they bring down the blended inheritance of the liberal subjects and the natural sciences; but now it is not for the children of the middle class alone, but increasingly for the new ranges of working-class pupils. Such a line could be traced in many other cities.

But of course the working class had been seeking education for over a century. In 1841 the energetic and ambitious founded ‘The Young Men’s Improvement Society’ which later gathered in hundreds of evening students and changed its name to ‘The Huddersfield Mechanics’ Institute’. It expanded, until in 1873 it was taken over by the local board, and developed into the Technical College of today, and the function of a secondary technical school was assumed by the new school of Millcross. Of course there were many other educational bodies formed by the working class – Co-operative Colleges, Labour Colleges, Forums and union centres, and such like – but the direct impetus from the working class did not create any secondary schools. The Technical College was an indirect result, and this is still evident today as the apprentices stream in from work; yet at the level of state education through the grammar schools, the middle-class pioneers commanded the day. The working-class child today shares the final results of their energies. Four grammar schools then, stemming from the middle class; and today on the site of the old Mechanics’ Institute stands a Working Men’s Club.1

Before the passing of the Elementary Education Act of 1870 Huddersfield spent nothing publicly on education; in 1960 it supported almost 20,000 pupils. It offers 29 primary schools for all social classes, and around these is a fringe of seven small prep schools. Since the war, nine secondary modern schools have been opened, and these are largely filled with working-class pupils.2 For children who fail their eleven plus, there have been two private secondary schools with a strong commercial bias. Yet since the abolition of fees by the 1944 Act these two have lost ground, and one is now about to close down. The middle-class parents who patronized them before are either more successful now at getting their children through the selection examination, or they are well contented with the secondary modern schools, or they pay more and send their boys and girls to boarding school. Everyone working in this field knows that since 1944 there has been a shift in middle-class education, but no one has altogether defined it.

Huddersfield seems not much different in its educational provision from other English cities, except that its wealth and its civic pride have helped it to be one degree more successful. We can measure this, in one sense, by the annual award of State scholarships. If we calculate that the Ministry makes 1,850 such awards each year, then in 1960, by winning 15, Huddersfield gained three times the number expected for a place of its size. A similar prominence is reflected in the yearly Oxford and Cambridge lists.

We now want to focus attention on this upper area of the four main grammar schools: the road to college, university, and the middle-class professions. Who are the children who travel this road? How does it affect them, and in particular how is the process felt by the working-class child and the family from which he comes? – for Huddersfield is very largely a working-class city.

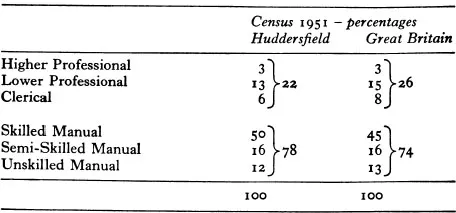

TABLE 1

Social Class of Occupied Men

Table 1 shows that at the 1951 census the city had rather more than the national average of manual workers. If we split the population up into manual workers and the rest, and call the former ‘working class’ and the latter ‘middle class’, then Huddersfield is 78% working class and 22% middle class. But if we now consult the records at Marburton College, Ash Grange, Abbeyford and Thorpe Manor, and examine the children who leave Huddersfield’...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Original Title page

- Original Copyright page

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Part One

- Part Two

- Appendix 1 Further Research

- Appendix 2 Further Reading

- Index