![]()

1

Changing current account patterns in the 1970s

From the point of view of efficiency of resource allocation a flow of capital from capital-rich to capital-poor nations could be expected as a normal state of affairs. Such inflows on capital account would provide finance for current account deficits, the latter reflecting a rate of investment spending in excess of domestic saving. Countries would be expected to borrow on the basis of this investment motive provided that rates of interest on world capital markets remained below the marginal returns to new investment projects within the countries concerned.

In attempting to interpret the pattern of current account balances between countries in the 1970s it is useful to note that such surpluses or deficits reflect financing decisions on the capital account. While the actual pattern of financial flows in the decade is the subject of the next chapter, a brief review of motives behind international borrowing will be presented here. Other than the investment motive for international borrowing at least two other motives can be identified. These have been called the ‘consumption’ and the ‘adjustment’ motives (Eaton and Gersovitz, 1980). Having defined them, the chapter will go on to employ the terms in a consideration of the special requirements thrown up by the oil price increases of 1973–4 and 1978–80.

It will be seen that the ‘adjustment motive’ in this new context shades into the motive for investment and further emphasis will be given to investment for this reason. Additionally it has recently been suggested in the literature that the pattern of adjustment by the world economy to higher oil prices in fact reflects the enhanced importance of the investment motive behind the flow of funds to LDCs. This new view, which may be of fundamental importance, will be outlined in this chapter and assessed critically in the next. It is an argument which goes beyond the immediate impact of the oil crisis.

How then may a country justify borrowing for purposes of consumption? In the first instance, a country anticipating rapid income growth in future years may wish to borrow and allow consumption to rise in the present period against the ‘security’ of the growing income stream. Perhaps more usually, a country facing relatively sharp swings of its year on year income around a stable trend may want to borrow to smooth its consumption patterns between years. Such may be the situation of a primary exporting country dependent on world market conditions facing a small number of commodities, and it is for such purposes that the compensatory financing facility evolved within the IMF.

In contrast to the cases of the investment motive and the first consumption motive, where indebtedness tends to rise rapidly in the early years, the consumption ‘smoothing’ motive would not be expected to change the country's overall indebtedness over the course of a full cycle. In reality, of course, the two consumption motives do share a complication of which the investment motive is theoretically free. Whereas a viable investment financed by foreign funds generates its own income from which service payments (interest and amortization) can be extracted, the repayments associated with consumption loans of either type must be met from the government's general budget. In principle the service payments would be a prior charge on government revenue and if international indebtedness is rising as a fraction of national income, as for instance in the early years of the first consumption motive mentioned, tax revenues will gradually have to rise as a fraction of income, or other public spending will have to be cut, in order to meet the service payments involved (Newlyn, 1977, p. 102).

A similar prior charge on government revenues is generated by the borrowing undertaken for the adjustment motive. The need for adjustment might arise due to a cumulative loss of international competitiveness leading to a balance of payments crisis. Immediate application of measures to deal with the situation would probably involve severe domestic deflation together with exchange rate depreciation. The use of international borrowing, in such instances typically from the IMF credit tranches, would enable the country to undertake the necessary adjustments over a somewhat longer period, thus avoiding the worse ‘stagflationary’ effects. It is to be hoped that relatively small adjustments to the country's resource allocation in favour of the foreign trade sector would suffice.

What then were the salient features of the adjustment motive for international borrowing in the aftermath of the oil price increase? Unlike the more traditional need for balance of payments support, often provided and supervised by the IMF during adjustment of domestic economic policies, the requirement was for adjustment to an exogenous change in countries’ international trading positions. That is, there was an impairment of import capacity over the medium term reflecting a fall in real national income. Secondly, again in contrast to the earlier adjustment problem, the need, although varying with differing national circumstances, was imposed simultaneously on a large number of countries. Thirdly, both exogenously and simultaneously, the export prospects facing LDCs markedly deteriorated as world economic growth declined in the years subsequent to the formation of OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries).

In the aftermath of the first oil price increases between 1973 and 1978 the oil-exporting countries used about half of their increased real resources in the purchase of goods and services primarily from developed countries (DCs). The other major development, quantitatively, however, was that the industrial countries reduced their rates of economic growth. On the average they were some 2.5 percentage points below the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) growth rates of the preceding decade (IMF, 1980, p. 74). By no means all of this reduction was the direct result of the rise in oil prices and, indeed, counter-inflation policies and issues relating to declining productivity growth in the developed countries were probably crucial. None the less, the oil price increases rendered difficult policy issues the more intractable. The outcome was that a collective deficit on the OECD countries’ balance of payments of some $8 billion in 1973 had been converted into a surplus of some $30 billion by 1978. As the World Bank (IBRD) comments,

… reduced deficits are not themselves evidence of successful adjustment; if they are achieved simply by slowing down activity, they underwrite the contractionary effect of higher oil prices. [IBRD, 1981, p. 9.]1

For a number of reasons, some of which, like declining productivity trends, may be fundamentally long lasting, the developed world responded in a quite conventional way to the deterioration of its trade balances experienced during the 1970s. In discussing the appropriateness or otherwise of this response, given our focus, it is not intended to discuss directly the efficiency of the counter-inflation strategy that has come to dominate policy making in many of the major industrial nations. From the point of view of the global economy, however, one point should be emphasized. The rise in real income of the oil-producing nations was matched by a decline in the current real income of the oil-importing nations. It was therefore appropriate that the domestic absorption of goods and services by these latter countries should be curtailed, but this does not mean that a general deflationary policy was appropriate on these grounds. The key to this point lies in the fact that world real income had not been reduced but rather redistributed in favour of oil producers who were inclined to accumulate financial assets with a substantial fraction of their increased income. Deflation of the world economy was therefore not called for; instead global adjustment needed to be in the form of a shift from consumption spending towards investment spending to match the increased potential supply of loanable funds.

If, for a moment, however, we visualize the world economy as two blocks, the global deflation that actually occurred can be seen in terms of the more traditional theoretical concern with the ‘transfer problem’. This was initially concerned with the conditions under which attempts by one nation to transfer real resources to another, by making financial provision to do so, would in fact be successful after economic ramifications had been taken into account. After World War I German reparation payments to the victorious countries were a crucial early area of application of this theory.

In the present context the possibility of ‘global’ deflation, given sufficiently high incremental savings ratios out of transfer receipts in relation to the propensity to spend these receipts on imports, is established at least in a Keynesian framework (Johnson, 1958). As the oil-exporting countries had high marginal propensities to save out of their extra ‘transfer’ income and as their import spending, at least initially, was low, the deflationary results would be understandable. As Johnson's analysis indicates, the role of capital movements between the two groups becomes important in determining the final outcome.

On this interpretation of events it would have been quite feasible for world output growth to continue undiminished following the rise in oil prices. While the rise in energy costs may have reduced the increment to output for each unit of investment spending (as more expensive plant was ordered to economize on fuel), the rise in availability of investment funds should have at least compensated for this effect. Against this background, what in fact happened to the growth performance of the world economy?

The slowing of growth is most clearly marked in the main industrial countries. Whereas, during the 1960s, they had grown at around 5 per cent a year, the rate dropped to an average of 3.3 per cent during the 1970s.

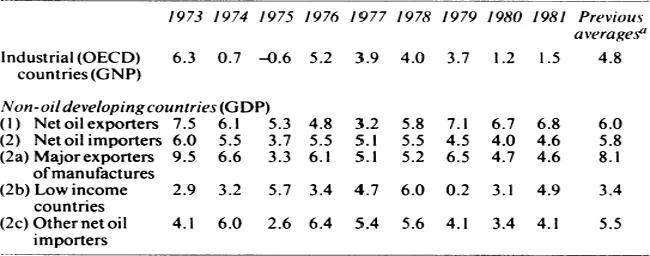

Table 1.1 shows the analytical subgroupings used by the IMF in its global report. ‘Net oil exporters’ are countries whose oil exports (net of any imports of crude oil) did not amount to two-thirds of their total exports and did not amount to 100 million barrels a year (IMF, 1980, p. 24). This would include countries like Mexico, Egypt, Gabon and Bolivia. The low income countries are thirty-eight in number with 1977 per capita gross domestic product (GDP) below $300, India excluded. India is added to the ‘major exporters of manufactures’ group. This includes most of the middle income countries and newly industrialized countries (NICs). There are twelve such manufacturing exporters including India and interestingly they account for well over three-fifths of the combined GDP or total exports of all oil-importing LDCs. This compares with only 12 per cent and 6.7 per cent respectively for the thirty-eight low income countries. The remainder are fifty middle income countries (GDP per capita in excess of $300 in 1977) whose exports are mainly of primary commodities.

Table 1.1 Percentage changes in output 1973–81

Source: IMF (1981), Tables 1 and 2, pp. 111–2.

a Industrial countries = 1962–72; non oil-developing countries = 1967–72.

As may have been expected, the data suggests that the net oil exporters managed to maintain a rather strong growth performance. Compared with previous averages the net oil importers displayed a marked slackening following 1976 from around 6 per cent to 5 per cent. Of the subgroups it seems probable that the low income countries fared least well with some of the larger Asian states masking, in the averages shown, a rather severe deterioration in the smallest countries. If the 1960s are compared with the 1970s per capita income growth rates for this group declined from 1.8 per cent to 0.8 per cent.

The middle income countries comprising groups 2a and 2c in Table 1.1 performed well in comparison with both the industrial countries and the low income group. Thus gross national product (GNP) per person in the two groups averaged a 3.1 per cent growth in the 1970s in contrast with 3.6 per cent in the 1960s.

From a global point of view, then, a significant part of the adjustment to higher oil prices occurred in the form of reduced rates of growth, most notably in the OECD nations and, most painfully, in some of the lowest income countries. However, it is noteworthy that the middle income LDCs, and particularly the major exporters of manufactures, sustained fairly strong although somewhat diminished growth performances even in the wake of the second round of oil price increases. A major question to be addressed in the next two chapters therefore will be whether or not the adjustment in these countries followed the ostensibly desirable path of a shift toward a higher rate of investment spending together with a curtailment of consumption. What is important for the present, however, is that the middle income countries were sustaining a relatively impressive growth performance in these difficult years. Pending closer investigation, the earlier discussion suggests that this was ‘justifiable’ growth in the sense of adjustment to higher oil prices. Chapter 3 will examine this ‘dynamic’ adjustment process for two countries.

What do such modes of adjustment imply for international indebtedness? If countries are going to draw on the oil-based source of savings, the implication, of course, is that current account payment deficits would be the norm and must be financed by borrowing. Provided that the deficits were being generated by a sufficiently large increment to investment spending, the borrowing would represent sound adjustment by the countries concerned. These investments would provide the basis for the ultimate repayment of interest and principal when the oil-exporting nations gradually began to spend their accumulated reserves. From this point of view the physical location of the investments concerned would be of little consequence.

It is certainly the case that the distribution of the deficits between DCs and LDCs was extremely skewed. As a group the oil importing LDCs had a $7 billion current account deficit in 1973 which leapt to $33 billion in 19...