![]()

1

Development and globalization of a new trend in tourism

Malte Steinbrink, Fabian Frenzel and Ko Koens

Over the last two decades, we have witnessed the development of slum tourism in an increasing number of destinations in the Global South. Slum tourism is unmistakably gaining in importance in terms of both economics and the numbers of tourists. It takes place in various ways, but the most obvious and established practices are guided tours – be they coach, van, jeep, quad, bicycle or walking tours. In some cities guided slum visits already constitute an important element in the range of offers made by the urban tourism industry.

Arguably, every new trend in tourism allows wider reflections on tourism itself. Questions arise as to why it emerges precisely at a particular point in time and in a particular social context, and as to how and with what consequences it develops in different local settings. Slum tourism in the Global South is one such new trend in international tourism. We argue that the main characteristic of this phenomenon – often also called ‘slumming’ – is the touristic valorization of poverty-stricken urban areas of the metropolises in so-called developing or emerging nations, which are visited primarily by tourists from the Global North.

At first sight, slum tourism may look surprising and startling since it contradicts common notions of what tourists do during their holidays. The wish to see and experience ‘something else’ and to ‘distance oneself from everyday life’, as expressed in common holiday motives, usually refers to beautiful and relaxing encounters. Slum tourism doesn’t seem to correspond with these notions. This astonishment is often mirrored in the media. In order to find explanations for this ‘extraordinary form of tourism’ (Rolfes 2010), journalists especially tend to come up quickly with speculations about the tourists’ motives, and these presumptions are often the starting point of ethical debates and judgements about slum tourism (Schimmelpfennig 2010). Academic research has started to reflect on slum tourism, and this book aims at advancing the debates developing in the field.

There are two principal ways to try to understand the new trend. The first is to analyse current practices and the ongoing construction of the ‘destination slum’ in the Global South. The second is to look at historical processes of destination-making and at comparable tourist practices in the past. Most of the chapters in this book follow the first path and reflect on slum tourism on the basis of recent case studies. We therefore start this book by providing a brief overview of the origins and development of slum tourism.

How it started: early slumming in the Global North

The creation of every new destination or type of destination draws upon more or less established images and ideas about unfamiliar and distant regions and their inhabitants (Pott 2007). These images refer to stocks of standardized, long-standing ascriptions that arise in discursive processes occurring both within and outside tourism. Tourists and the tourism industry seek for discursive connectivity, reproduce these ascriptions and/or create new meanings and images, while reacting to social structures and their changes. New forms of tourism often have historical forerunners. This also holds true for the new destination type of the slum in the Global South.

Curiosity about slums appears to be as old as the slum itself: the term ‘slum’ evolved in eighteenth-century London. Originally, ‘slum’ was a slang word – presumably of Irish origin – coined by slum dwellers. It only found its way into standard English around 1840, and was then used by upper-class Londoners to describe the East End. During the same period, the word ‘slumming’ evolved in London’s ‘West Side Lingo’ (Steinbrink 2012). The term described a burgeoning practice of members of London’s higher classes visiting the East End, often guided by police officers in civilian attire, journalists and clergymen. These early slummers were frequently wrapped in the cloak of concern, welfare and charity; however, this changed in the second half of the nineteenth century, when slumming developed into a more purpose-free leisure-time activity (Koven 2004).

In the 1880s, slumming emerged in New York, marking an increasing ‘touristification’ of the phenomenon. Wealthy tourists from London had imported slumming, eager to visit the poorer areas in New York (e.g. Bowery) in order to compare them with ‘their’ slums at home. Tourist guide books included routes for walking tours through various impoverished areas (Keeler 1902; Ingersoll 1906). Additionally, the first commercial tour companies specializing in guided slum visits were established in Manhattan, Chicago and San Francisco. In the early twentieth century, ‘slum tourism’ in a more narrow sense emerged for the first time, and slumming became an integral part of urban tourism (Cocks 2001: 174ff.).

The historic cases of slumming in London and the United States are quite well documented (Conforti 1996; Cocks 2001; Koven 2004; Ross 2007; Dowling 2009; Heap 2009; Steinbrink 2012; Seaton in this volume). These studies also point to continuities in the development of slum tourism, for example in the way that tourists gaze (Urry 2002) on slums seeking the ‘low’, the ‘dark’ – the ‘unknown side of the city’. The examples demonstrate that the slum was discursively construed as well as touristically staged and experienced as ‘the other side of the city’, and as the ‘place of the “Other”’. At the same time, they illustrate that this ascribed ‘Other’ had often been a lot more than just the ‘economic “Other”’ – the slum was more than just the ‘place of poverty’. The slum was also a surface for the projection of a ‘societal “Other”’. Dominant modes of social distinction were negotiated through the topography of urban landscapes. However, these dominant modes and characteristics of the ‘Other’ varied from one historical period to another and depended on the respective social context.

Steinbrink’s (2012) reconstruction of the genesis of slum tourism discusses these changes: in the industrializing Victorian London, shaped by extremely rigid moral values and norms, the slums were seen as places of moral decay and libidinal liberty. The slum was socially constructed as the place of the ‘immoral “Other”’ (‘moral slumming’). In the ‘modern’ US of the early twentieth century slumming took a different form. Between 1880 and 1920, millions of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe and from Asia entered the US, challenging the predominant understanding of the American identity as ‘white, Anglo-Saxon and protestant’. The guided slumming tours of the time can be seen as a response to this. They predominantly visited ethnic urban enclaves and constructed immigrant communities as ‘ethnic (pre-modern) “Other”’ (with the most popular examples being ‘China towns’ and ‘little Italies’). Through this ‘ethnic slumming’, the immigrant groups were symbolically assigned to their place – both spatially (i.e. within ‘their’ quarters) and socially (i.e. at the margins of society) (ibid.).

While slum tourism in the Global South has forerunners in the North, its occurrence and its remarkable dynamism in many so-called developing countries and emerging economies is new. The present globalization of this form of tourism can be understood as a further stage of development of slum tourism. The two examples of historic slumming in the North already indicate certain continuities and changes. The territorial ascription of the ‘Other’ in the slum seems to be a constant, whereas the formation of the respective ‘Other’ is subject to alteration depending on the social context. This insight might help when dealing with the recent phenomenon. It could mean examining slum tourism against the background of a globalized world society. Steinbrink and Pott (2010) point out that slumming in the Global South is no longer merely about ‘the other side of the city’, but essentially seems to concern the ‘other side of the world’ (‘global slumming’). This brings the process of constructing a ‘global or world-societal “Other”’ to the foreground. Hence, the globalization of slum tourism needs further explanation. Questions arise regarding the interplay of the new global form and the local practices of slum tourism in different places, pointing at the importance of local factors in this process of ‘glocalization’ (Robertson 1995) of slumming.

In the next section, we briefly trace the occurrence of the phenomenon in different places in ‘the South’ and at different points in time in order to show how slum tourism spread across the globe and how it developed in different local settings. It can be seen as an attempt to illustrate the dynamics of its globalization.

The recent phenomenon: slumming in the Global South

To answer the question of when slum tourism in the South actually started evokes reflections about the definition of tourism. Already in Victorian London, pioneer ‘slummers’ went into slums for other reasons but leisure: there were journalists in search of a good story, academics looking for an interesting research field, and social reformers, political activists and ‘helpers’, either by profession or by altruism (Koven 2004). Such ‘professional and altruist slummers’ played an important role in the development of slum tourism historically. Professional slummers today continue to significantly shape the image of slums in the Global South through their photos, films and reports, contributing to the discursive production of the slum as an attraction. They are also actively involved in the development of the actual practice of slum tourism by taking other visitors into ‘their’ slums. While professional and altruist slummers pave the way for slum tourism, they can be differentiated from people who visit poor urban areas as a leisure-time activity (‘leisure slummers’). We propose talking about slum tourism in a more narrow sense when the visits take place within the organizational context of tourism. Once the (slum) tourism infrastructure has developed in a particular destination, professional slummers will be likely to use this as well (e.g. researchers who stay in B & Bs situated in a slum or journalists who use commercial tour guides for their inquiries), and the lines between professional slummers and slum tourists blur.

The presence of professional and altruist slummers is not the only precondition for the development of slum tourism. While professional slummers are found in uncountable slums all over the world, organized slum tourism has only evolved in particular places. In the following section we present a list of slum tourism destinations that developed since the early 1990s, highlighting preconditions and initial impulses of their emergence. It is only a first step to trace the development in a comparative perspective and it remains a central research question for slum tourism research to better understand the specific conditions that enable slum tourism development in particular destinations (Frenzel in this volume).

It is widely accepted that the more recent form of slum tourism started in South Africa (Rogerson 2004; Mowforth and Munt 2009; Butler 2010; Rolfes 2010). During the time of apartheid, tours were already conducted in ‘non-white group areas’, both by the apartheid regime (as official tourist attractions), and by critical NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and political groups for international solidarity activists (Dondolo 2002; Frenzel in this volume). After the end of apartheid legislation and international sanctions, township tourism has expanded across all major cities in the country (with the main township destinations situated in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban). In Cape Town alone, tours are offered by forty to fifty operators. We estimate that, altogether, around 800,000 tourists currently participate in organized tours. Township tourism has become an integral part of city tourism in South Africa.

Parallel to the development of township tourism in post-apartheid South Africa, slum tourism also started in Brazil. The occurrence of favela tourism is linked with the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, where journalists and political activists were the first to tour Rocinha, a settlement known as the largest favela in the city (Freire-Medeiros 2009; Frisch 2012; Frenzel in this volume). From these first informally guided tours a commercial tourism branch has grown, and about eight different commercial favela tour companies and about twenty independent guides are operating in the city today. We estimate that, in 2011, more than 50,000 tourists participated in organized favela visits in Rio. And this number will probably increase with the coming FIFA World Cup in 2014 and Olympic Games in 2016. More recently, favela tours are also offered in São Paulo and Salvador de Bahia.

The figures from Brazil and South Africa indicate that slum tourism is already a highly professionalized business in these two countries. This includes increasing diversification, particular in Cape Town and Rio de Janeiro. Apart from guided tours, both destinations now offer elements of adventure tourism (e.g. quad, bicycle and motorbike tours and even bungee jumping), accommodation in the slum and specialized tours focusing on music, food or ecological aspects.

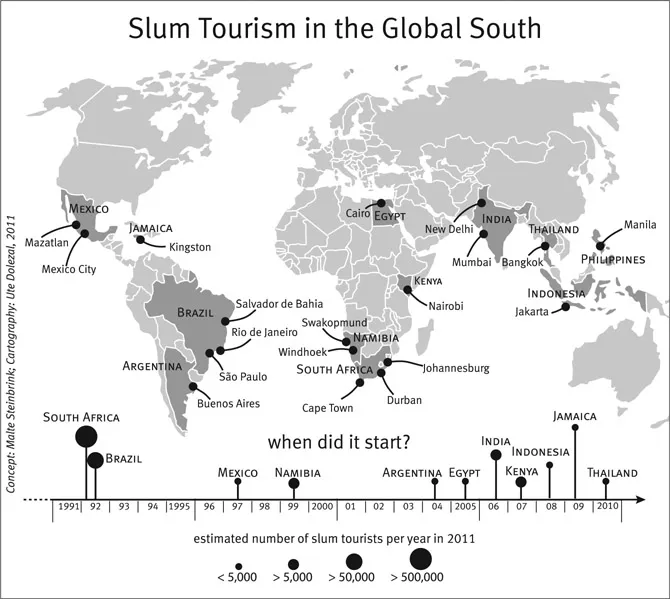

In the meantime, slum tours have also emerged in other countries of the Global South, and this development is gaining in pace. It is difficult to give precise evidence of all different locations in the Global South where slum tourism is practised. Nevertheless, in the following paragraphs we have tried to provide a chronological overview of the places where slum tourism has been conducted in an organized form (see Figure 1.1).1

During the 1980s, the ‘Smokey Mountains’ in Manila in the Philippines had become a symbol for urban poverty in the Global South. In the early 1990s, a tour operator started offering tours to this huge garbage dump, where thousands of people lived and worked. To our knowledge these tours stopped in 1993, when the dump was closed. Most inhabitants had to move to Payatas, another dump, which collapsed in 2000 in a landslide that buried hundreds of people.

Another example of tours visiting a garbage dump is in Mazatlán, Mexico. From around 1997 an evangelical North American church community has offered ‘garbage tours’ to tourists from various resort zones and even from cruise ships stopping in Mazatlán. Half-day excursions are provided that start by driving through some of the city’s poorer neighbourhoods and end with a visit to a local garbage dump and the people living and working there as garbage collectors (Dürr 2012). More recently, commercial slum tours have also started to be offered in impoverished neighbourhoods in Mexico City. Using names like ‘undercover tours’ or ‘safari tours’, the tours take tourists around feared ‘barrios’ such as Tepito.

Inspired by the experiences in South Africa, township tours have been offered in Namibia since the turn of the century. The main destination is Katutura, Windhoek – a settlement founded during the apartheid era after forcible evictions of African town dwellers in 1959. There are at least ten companies (including an official tour offered by the city council) specializing in township tours in Windhoek and two in Swakopmund (de Bruyn 2008).

Figure 1.1 Times and places of slum tourism in the Global South.

In December 2004, slum tourism started in Argentina. A former movie location scout, Roisi Martin, started to offer visits to ‘Villa 20’ and ‘Trava tours’ (visits to a transvestite brothel in the red-light district in Buenos Aires) (Marrison 2005). Another company, ‘Villa Tours’, takes tourists to villas miserias on the outskirts of the city for US$70 a person. Since very recently, aerial tours have also been offered by a flight company:

to allow a peek inside these mysterious communities, and to give people an idea of the ‘miseré’ in which the inhabitants live. This is the only safe, secure and unobtrusive way to get a glimpse of this gritty side of Argentina.

(Buenos Aires Air Tours 2011)

In Egypt, slum tourism emerged in 2005 when American eco-activists T.H. and Sybille Culhane started ‘Solar CITIES Urban Eco Tours’. Inspired by their experiences of urban eco tours in Rio’s favelas and of eco township tours during the Earth Summit 2002 in Johannesburg, these urban planners developed an inner-city eco tour through the slums of Darb al-Ahmar and Manshiyat Nasser (‘Garbage City’) in Cairo, which is guided by local tour guides (Solar CITIES 2008).

One year later, in January 2006, English social worker Chris Way and his Indian counterpart Krishna Poojari started ‘Reality Tours and Travel’ in Mumbai, India, after Way had got to know of the concept of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro in 2003. Slum tourism in India is n...