![]()

1Introduction

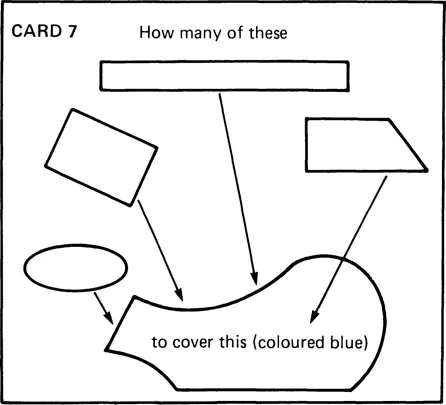

Dan is a bright 6-year-old in his third year of infant schooling. In his number work he has been proceeding through the mathematics scheme, dealing quickly and easily with assignments on capacity, weight, volume and length. His current work is on area and he has already completed six work cards on this topic. In the observed session he began work on card seven for which the teacher’s stated intention was that Dan should gain experience with irregular shapes.

The work card is reproduced below (Fig. 1.1). No teacher instructions were provided; he simply took out the card and commenced work. His first concern was what to call the oval shape on the extreme left of the card, and therefore he asked the teacher. She told him that she thought it was an ellipse and asked why he wanted to know. He replied that he wanted to write it down. Because his teacher was unsure she asked another teacher who, after perusing the maths book, told him to call it a segment.

FIG. 1.1

Satisfied, he returned to his task, roughly tracing over the minor shapes and, equally roughly, cutting them out. He fitted them over the shape one at a time to see how many fittings it took to cover it. He then asked the teacher the name of the extreme right-hand shape—a trapezium. She told him it was a rhombus. He wrote it down.

At this point he was called out to read to the teacher and returned 7 minutes later to continue work on his card. His answers were as follows:

11 segments cover the blue thing

6 rhombuses cover the blue thing

4 diamonds cover the blue thing

8 oblongs cover the blue thing

In another third-year infant classroom Alan was given a writing assignment. His teacher showed him a set of cards, each of which illustrated people at work, and suggested that he write about one of them. He selected the card showing a bus driver and took it to his desk.

He paused for 5 minutes, apparently thinking about what to write. Eventually the teacher approached and asked him what his first sentence was going to be. He replied, “I went on a bus to school.” He started his writing and then searched through his word book for “school.” He failed to find it and consulted his teacher. She helped him spell it and then explained about the “sleepy c.” He went back to his desk and continued to write for several minutes, reading aloud as he wrote. He hesitated over the word “sometimes” and went to the teacher to ask how to spell “times.” There was a queue at the teacher’s desk. Whilst waiting he found the word under “t” in his word book and shouted out to the teacher, “I’ve found it, Miss. It’s here.” A few minutes later he went to the teacher again to ask how to spell “gives.” After a brief wait in the queue he was given the word. Later he went out again, showed the teacher the “f” page in his word book and asked for the word “fing.” The teacher gave him the spelling of “thing.” After 5 more minutes’ writing he took his word book again to the teacher. After a brief wait he showed her the “i” page and asked her how to spell “eat.” In the next 2 minutes he went out to check that “going” ended in “ing,” that “am” was spelt “a-m-e” and that sleep was spelt “s-e-e-p.” In each case the teacher responded with the correct spelling.

Twenty-three minutes after choosing the work card Alan took his story out to have it marked. He had written, “I went to school on the bus and I went home on the bus sometimes the bus driver gives me something to eat Im going horns I am going to sleep til morning.”

These two brief sketches are tiny portions of the classroom lives of Dan, Alan and their respective teachers. They were observed in the process of the research to be reported in this book. They are, of course, grossly selective. Missing from the descriptions is any sense of the classrooms and their inhabitants, any hint of the bustle, the background noise and the aura of the classroom. Also missing is any account of the general learning environment provided by the teachers surrounding Alan and Dan. The experienced reader may have superimposed on these descriptions images of wall charts, word lists, tables, boxes of apparatus and 30 or more children clamouring for information and willing to give assistance. It will also have been recognised that although Dan and Alan were not told what to do they knew the rules of the classroom. Despite being presented as disembodied events, the tasks assigned were small elements in large programmes of work.

Selective and disembodied though these descriptions undoubtedly are, they capture significant aspects of the learning experience of children in the infant classroom. Children predominantly work on their own on tasks assigned and structured by their teachers. Examination of the pupil and teacher behaviour on these singular tasks raises a number of important questions regarding the quality of pupil learning experiences. What did the children achieve from working on their respective tasks? To what extent was Dan’s knowledge of area extended? Did Alan’s written expression improve? What did they each learn about learning and the use of the resources available to them? Did they know what their teachers intended? Were they equipped to make the best of their learning opportunities? Or, put another way, were the learning opportunities well matched to the attainments and capacities of the children? How did the teachers rate the children’s work? What did the teachers learn about Dan and Alan that would help them select suitable subsequent learning experiences?

These questions are not concerned with how much the children learned but with the quality of their learning experiences. They are concerned with the nature of learning and the manner in which the environment provided by the teacher fosters or inhibits the business of learning.

Very little is known about the quality of learning experiences provided for pupils in schools, although some doubts have recently been expressed about some aspects of them. Both in Britain and the United States studies have concluded that in some parts of the primary school or early grades curriculum, large percentages of the work set are not well matched to pupils’ attainments (Anderson, 1981; HMI, 1978). The consequences of such provision, it is suggested, is that high-attaining children are “not stretched” (HMI, 1978) and that low-attaining children are mystified (Anderson, 1981).

This situation is apparent despite the availability of an abundance of advice for teachers, particularly from psychologists who have been energetic in offering teachers prescriptions on how to design ideal learning environments. This advice is very familiar to educators. In the Cockroft report on mathematics education, for example, it was recognised that in specifying good mathematics teaching “we are aware that we are not saying anything that has not already been said many times and over many years (Cockroft, 1982, p. 72).”

It is now very widely recognised that such advice has had very little impact on the practice of teaching (Atkinson, 1976; Ausubel & Robinson, 1969; Glaser et al., 1977). There are, no doubt, many reasons for this. Some arise from the manner in which those who have studied teaching and learning have oversimplified the lives of classroom participants (Bronfenbrenner, 1976). Until recently, research on learning had largely ignored the processes of teaching and research on teaching had neglected the processes of learning. Consequently, some of the advice to teachers emanating from research was consistent only with theories of cognition, which did not attend to the constraints on the teacher.

The approach to generating advice to teachers from theories of cognition has been adopted by Ausubel (1969), Bruner (1964), and Posner (1978), among others. It is also manifest in most of the attempts to generate teaching implications from Piaget’s theory (Duckworth, 1979; Schwebel & Raph, 1974). However, the impracticality of this approach to improving teaching has long been asserted (cf. Sullivan, 1967), since it typically ignores, for example, the teacher’s limited resources of materials and time, and the attention she must pay to the social and emotional needs of her pupils. Also, the teacher’s autonomy is generally overestimated. Class teachers have little choice in the teaching materials at their disposal and the timetable and other organisational features of the school are generally imposed on them.

In contrast to the generation of prescriptions from cognitive psychology a vast literature from classroom-based research documents the relationships between pupil achievement and many aspects of the classroom setting (cf. Haertel et al., 1983, for a recent summary), and these, too, have been used to provide prescriptive advice to teachers. A recent, and typical, example is that reported by Denham and Lieberman (1980) who, among other things, exhort teachers to make tasks clear, obtain and sustain pupil attention, assign appropriate reinforcements and feedback and cover the material which is to be tested. That these processes are important has never been in contention. Indeed, it has been considered that such research findings have barely caught up with common sense (Jackson, 1967; McNamara, 1981). If teaching were so simple, it is difficult to understand why teachers behave otherwise in classrooms. Additionally, the dangers of adopting such tactics, such as spending disproportionate amounts of time on accounting and testing activities, and a concentration on those parts of the curriculum which are to be tested, have been ignored.

In attempting to account for the limited effect that research on teaching and learning has had on classroom practice, some researchers have suggested that classroom life is much more complex than researchers have imagined. In this view, attempts to change practice must be based first on an understanding of this complexity (Bronfenbrenner, 1976; Doyle, 1979a, 1979b).

Doyle has developed a model of classroom learning processes which attempts to capture some of the subtle processes involved as teachers and learners adapt to each other and to the classroom environment. In order to understand these processes he argues that the main features of the classroom environment and the resources of those who inhabit it must first be described.

Doyle suggests that classrooms are potentially rich sources of information. They are laden, for example, with books, charts, displays and verbal and non-verbal behaviour. However, these sources are not consistently reliable as instructional cues. Teachers and pupils can, for instance, easily misinterpret each other’s intentions and thoughts. Additionally, in Doyle’s view, classrooms are mass processing systems. By this he means that many people take part and many interests and purposes are served. Many events occur at a given moment and a consequence of their simultaneous occurrence is that participants have little time to reflect. Decisions have to be immediate.

This potentially complex information environment is inhabited by teachers and pupils who are considered, in Doyle’s model, to have limited capacity to deal effectively with the abundance of information. They cannot attend to many things at once. These limitations are such that selections must be made from available sources of information. Strategies must be developed to optimise these selections in order to increase the manageability of classroom life. To this end Doyle suggests that it is necessary to make many actions routine in order to focus attention on monitoring the environment. This process of automation may be compared with that of learning to drive a car. Initially basic controls demand almost all of the driver’s attention. Once the basics are made automatic, attention is available for the road. When reading the road becomes routinised or automated, attention is available for erudite conversation with the passengers.

In Doyle’s model learning is a covert, intellectual activity which proceeds in the socially complex, potentially rich environment described earlier. In respect of learning, the crucial features of the environment which link teachers to learners are the tasks which teachers provide for pupils.

The pupils’ immediate problem with regard to these tasks is to gain an understanding of what features of their task response the teacher will reward. In Doyle’s terms the pupils must develop “interpretive competence,” i.e., they must learn to discern what the teacher wants. This is not always easy because both tasks and rewards may be complexly and ambiguously defined by teachers. The following example observed in this study illustrates this.

The teacher talked to her class of 6-year-old children for 45 minutes about the countries of origin of the produce commonly found in fruit shops. This monologue was illustrated using a small map of the world and extensive reference was made to many foreign countries. She finished by asking the children to “write me an exciting story about the fruit we eat.” The children had to decide what she meant by this! They were helped in part by the fact that they had heard this same instruction before in respect of other tasks. In fact the children wrote very little. They took great pains to copy the date from the board although the teacher did not ask them to do this. It was presumably taken for granted as part of the task specification. They formed their letters with great care and used rubbers copiously to correct any slips of presentation. Whilst this went on the teacher moved about the class commending “neat work” and “tidy work” and chiding children for “dirty fingers” and “messy work.” No further mention was made of “exciting” content or of “stories.” It seemed that the children knew perfectly well what the teacher meant when she asked for an “exciting story about fruit” even though in this case the teacher’s overt task definition, her instructions, stood in sharp contrast to the rewards she actually deployed.

Once children have discerned what teachers want there is some evidence that they offer resistance to curriculum change (Davis & McNight, 1976). They reported that children showed a marked lack of interest and an increase in disruptive behaviour when new demands were made on them. This was particularly so when they found it difficult to discern the manner in which to fulfil the demands (as is the case in problem-solving approaches to learning, for example). Doyle (1980) suggests that pupils learn how to respond to one form of task specification—an achievement which brings predictability to their classroom lives—and resist having to discover a new specification and how to fulfil it.

This view of the classroom provides a cautionary note about the dangers of over-simple analysis and interpretation of classroom learning. Implicit in it is the message that before attempts are made to alter the quality of learning experiences provided in the classroom, researchers should endeavour to understand the nature of current provision and identify the forces which sustain and or inhibit learning.

In order to account for classroom learning it seems clear that the processes of task allocation and task working must be monitored in classrooms. It also seems necessary to identify the intellectual demands made by teachers on children and the manner in which children meet, avoid or adapt these demands.

The research reported here attempts to address some of these problems. The study has been influenced by Doyle’s theory of the potential complexity of classroom life, and was designed in recognition of the view that learning proceeds in a complex social situation and that the notion of quality must refer, at least, to the context as well as the content of learning experiences.

![]()

2Research Design

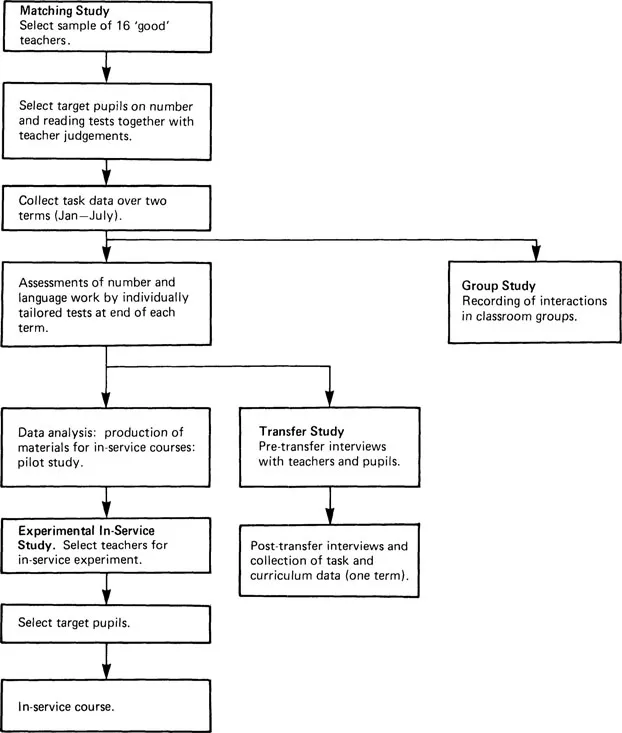

The focus of the study is on the nature and content of classroom tasks and the mediating factors which influence their choice, delivery, performance and diagnosis. In the study itself these were considered holistically but for the purposes of clear description the whole has been broken down into four sub-studies. The matching study which considered the entire task process in classrooms in aspects of number and language work led into two separate strands: the first was the transfer study in which a sample of the same children were followed through into their next class or school. The second was the utilisation of the data from the matching study to develop an experimental in-service course for teachers in an attempt to explore problems in the improvement of the matching process. Finally the grouping study investigated the effect on task performance of working in classroom groups.

Figure 2.1 is a simplified representation of these studies.

FIG. 2.1 Simplified research design.

The research approaches for the matching, transfer and in-service studies are described below. The design features of the grouping study are presented in Chapter 8.

THE MATCHING STUDY

This study was specifically concerned with the task process in all aspects of language and number work in classes of 6- to ...