![]()

1 Introduction

Chin Hee Hahn, Shujiro Urata and Dionisius Narjoko

There is no doubt that economic growth is not only the single most important subject in economic science but also the main vehicle for raising the living standards of thousands of millions of people in the world. Also, economists have long recognized the gains from international trade. So, is international trade, or more broadly, globalization, related to economic growth? It might be fair to say that most, if not all, economists believe that globalization and economic growth are intimately related and, furthermore, that globalization has brought enormous benefits for many countries and people. This belief seems justified if we look at the long-run historical experience of the world economy. Each of the two waves of globalization, the first corresponding to the period from the late nineteenth century to World War I and the second corresponding to the post-World War II period, was accompanied by high rates of growth of the world economy, by historical standards. The inter-war years witnessed a world-wide increase in protectionism and decline in trade, as well as stagnation of economic growth.

Scepticism with regard to trade or globalization has also persisted over the past decades, and the debates and controversies among economists and policymakers, particularly over the relationship between trade and growth, have soared to prominence in recent years. There are several reasons for this scepticism. First, various theoretical studies, prominently those based on endogenous growth theories, suggest that the relationship between trade or trade liberalization and growth is ambiguous at best; trade liberalization can lead to either faster or slower growth. Here, the key is whether trade liberalization facilitates international knowledge spillovers and/or whether trade liberalization increases the incentives to invest in research and development (R&D) or in human capital.

Second, the controversies are at least partly related to the mixed empirical evidence on the trade–growth nexus. While important empirical studies report a positive relationship between trade and growth, criticisms have been raised with regard to the data, measurement of trade policy, empirical techniques, and model specifications. The most notable examples are the controversies on cross-country evidence on trade and growth.1 Nevertheless, it is worth noting that, while the debate on the macroeconomic effects of trade on growth is still quite open, there are a growing number of studies that find positive correlations between trade flows and international knowledge flows. These knowledge flows are crucial for the realization of the dynamic gains from trade (Coe and Helpman 1995; Coe, Helpman and Hoffmaister 1997). For example, Coe and Helpman (1995) found that technology spillovers are higher when a country imports relatively more from high- rather than low-knowledge countries. In their subsequent study, Coe, Helpman and Hoffmaister (1997) reported that total factor productivity (TFP) in developing countries is positively related to R&D in their industrial country trading partners, and that the effect is stronger when machinery and equipment import data are used.

Third, but more importantly, even if international trade or globalization has brought about benefits for the world as a whole, there is a strong recognition that the benefits have not been evenly distributed, not only across countries but also across people within a country. After World War II, a reversal in protectionism started among the industrialized countries, spreading to the developing countries in the 1970s. Trade reforms were further expanded and consolidated in the 1980s and 1990s across the developing world: in South Asia, East Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe and, to a lesser extent, in Africa and the Middle East. Yet the results of trade reform have varied, and have sometimes fallen short of expectations (World Bank 2005).

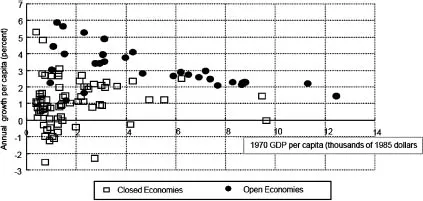

Indeed, the post-war growth experience is consistent not only with the beneficial effects of openness, but also with the uneven effects of trade on growth.2 Figure 1.1, from Sachs and Warner (1995), shows the relationship between the post-war growth rate of 84 countries and their initial income, distinguishing between ‘closed’ and ‘open’ countries by their own criteria. Here, the open countries are denoted by solid dots while the closed countries are denoted by blank squares. If we compare growth rates of open and closed countries, holding constant the level of initial income, the growth rates of open countries tend to be higher. Based on this finding, Sachs and Warner (1995) suggested that open countries tend to grow faster. Later, Lucas (2009) reinterpreted this figure, and suggested that, among the set of open countries, there is a convergence. However, Lucas (2009) also notes that even among the set of open countries there are large variations in growth outcome starting from the same level of initial income; in some cases, the growth rates of open countries fall far short of those recorded not only by other open economies but also by some closed economies. Furthermore, although systematic cross-country evidence of the effect of trade on within-country income inequality is hard to find, there is a growing concern that globalization has been an important factor raising within-country inequality, not only across skill groups but also across regions.3

Figure 1.1 Relationship between openness and growth.

Source: Adapted from Sachs and Warner (1995).

The World Trade Organization (WTO 2008, p. 113) succinctly summarizes the various concerns raised in this regard in the following two paragraphs.

Comparative advantage may be meaningless if the costs of shipping a product are higher than the costs of producing it. The overall gains for a country will matter little to those who lose their jobs as a result of specialization driven by trade. These people may have difficulties in taking up positions in expanding sectors because they are not adequately trained. The poor may be particularly vulnerable, since they do not have the means to ensure a smooth transition from one activity to the next.

Industries do not spread their operations evenly across countries, but tend to concentrate in particular locations. These dynamics can be self-reinforcing, leading to agglomeration in some places and de-industrialization in others. At the same time, with reductions in transport and other trade costs, production processes can be split up into more and more individual steps. This has allowed firms in remote locations to become leaders in specialized activities and to join international production networks. Others remain outside these networks, often due to institutional, administrative and other constraints.

The current state of our knowledge, as well as the past diverse experiences of countries, suggest that there are still many questions, old and new, that need to be explored in order to improve our understanding of various aspects of the globalization that we are facing today, including its consequences. Most of these questions are related to the relationship between globalization on the one hand, and growth, productivity, reallocation, location of industries and firms, employment and wage inequality, market structure, etc. on the other. Does trade and investment liberalization lead to economic growth and productivity improvement? Is there still a role for infant industry protection? Does trade and investment liberalization improve or worsen employment? Does trade have a disciplining effect on domestic firms? What are the relationships between trade, innovation, and the product choices of firms? Does trade and investment liberalization have differential effects on firms and industries? If so, what are the firm, industry and country characteristics that shape the relationship between trade/investment liberalization and various outcome variables? These are only a few examples of questions that need further scrutiny. Developing answers to these questions is likely to be a pivotal step towards maximizing the potential benefits from globalization, as well as sharing those benefits more widely not only across countries but also across various economic agents in a country. All studies in this report tackle some of the questions raised above.

One of the key features of this book – micro-data analysis of globalization – stems from the recognition that many of the old and new issues raised above can be addressed better by utilizing micro-data sets. We also expect that microdata analysis can potentially give us much richer information on various issues of globalization, such as the exact channels through which the benefits of trade materialize, the possible differential effects of trade and investment liberalization, and the existence of factors or policies that are complementary to trade and investment liberalization. In this regard, it should be noted that recent advances in theoretical and empirical studies based on firm heterogeneity have made a considerable contribution to our knowledge in this area.

There have been studies, both theoretical and empirical, suggesting that even in a narrowly defined industry there is considerable heterogeneity among firms, particularly in terms of productivity. According to these studies, industry-level productivity growth can arise through the entry and exit of firms, share shifting from less productive to more productive firms, and productivity improvement in continuing firms. Building on this literature, and following an influential theoretical work by Melitz (2003), a growing number of studies have examined the effects of trade on the process of industry productivity growth, that is, entry/exit and share shifting. In essence, his work and many of the variants of his model have shown that trade and trade liberalization can enhance the productivity of the aggregate economy by reallocating resources from less to more productive firms, even when there is no change in firm-level productivity. It has been argued that this effect provides another source of dynamic gains from trade, in addition to conventional channels, such as scale, variety, and the pro-competitive effect (i.e. lower markups), although others suggest that the heterogeneous-firm-based literature does not prove the existence of ‘new’ gains from trade. Regardless, it seems clear that the heterogeneous-firm-based literature has made a contribution to understanding more clearly the mechanism by which trade promotes productivity and growth. Some of the chapters in this book take this literature as their background.

A micro-data analysis of globalization is particularly interesting for East Asian countries.4 Above all, most East Asian countries are characterized by relatively open trade and investment regimes compared with other developing countries, and have recently experienced rapid de facto integration, not only among themselves but also with countries in other regions. Also, they have exhibited the most dynamic growth performances for the past decades. As a consequence, the effects of globalization are likely to show up in a relatively short period of time for the dynamic countries of East Asia. If this is the case, it is a great advantage for this type of research, given the usual constraint that micro-data sets are generally consistently available for only a relatively short period of time. So we expect that any proposed benefits or costs of globalization are likely to show up clearly in East Asian countries.

Another reason why East Asia is an interesting place for this type of research is that East Asia covers countries that are heterogeneous in many respects. They differ not only in terms of level of development and size, but also with respect to liberalization strategies and economic structures. In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) and migration flows, East Asia includes both home and host countries. These diverse country characteristics provide us with the opportunity to assess whether and how the effects of globalization differ across countries, and why.

Third, East Asia is an appropriate place for analysing the consequences of the so-called ‘second wave of globalization’. Irwin (2005), among many other scholars, noted that the second wave of globalization is distinguished from the first wave in that outsourcing, or the formation of international production networks, driven by multinational firms, has rapidly expanded across the globe. In fact, it has been pointed out that the formation of international production networks has been most marked in the East Asian region. As a result, a large share of trade, particularly intra-regional trade, in East Asian countries comprises parts and components, while trade between East Asia and other regions is still dominated by finished goods. One issue frequently raised has been regarding the potential of differential effects of trade in parts and components, as distinguished from finished goods, on growth and income distribution in home and host countries. Although there is a large and growing literature on this issue, some of the chapters in this book tackle it from a new perspective.

Finally, as it is well recognized, the rise of China and its integration into the world economy is probably one of the most important economic developments in the post-war world. Over the past three decades China has grown at nearly 10 per cent per year, driven by the expansion of a modern, export-oriented industrial sector. Moreover, the structure of China’s exports has also been changing rapidly, away from low-tech labour-intensive manufactures to medium- to high-tech skill-intensive products. China has also become the number one destination for FDI from more advanced East Asian countries such as Korea and Japan. China’s rise has had tremendous impacts through various channels not only on East Asian countries but also on the world economy as a whole. Most importantly, the rapid growth of China itself, and the rapid improvement in the living standards of more than 1.3 million people, has reversed the trend in world income distribution, which had been deteriorating for about 200 years since the industrial revolution. It has also changed the patterns of world trade and capital flows, as well as the prices of goods and commodities. It has deepened production fragmentation in East Asia to an unprecedented level (World Bank 2006). So how has China’s rise affected other East Asian countries? How has the formation of production networks affected China itself? Some of the chapters in this book address issues that might be related to this question either directly or indirectly.

Structure of the book and summary of the chapters

This book consists of nine studies covering eight East Asian countries: Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Thailand (two chapters), Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and one South Asian country, India. All papers address various issues related to the consequences of globalization. One commonality running through these papers is that they all carry out micro-data analysis. Another is that they examine whether there are any firm, industry, or country characteristics that affect the relationship between globalization and the outcome variables of interest.

Learning-by-exporting and productivity

Chapter 2 examines whether learning-by-exporting improves the productivity of firms, employing two alternative measures of TFP and utilizing plant-level panel data on Korean manufacturing from 1990 to 1998. The propensity score matching technique was employed to address the selection bias arising from endogenous export market participation. A large and robust learning-by-exporting effect is confirmed. The study further finds that the degree of learning-by-exporting effects depends on various plant characteristics. The effects tend to be more pronounced for plants with high export propensity and for small plants. It also finds that immediate productivity gains after exporting are larger for plants with high skill intensity, but that in the longer term the gain seems larger for plants with low skill intensity.

Trade, productivity and innovation

The interrelationships between trade, productivity and innovation are explored in Chapter 3, for the case study of Malaysian manufacturing over the period 1997–2004. The study in this chapter utilizes firm-level data from innovation surveys. This study has found that the link between exporting and productivity is weak for Malaysia. Productivity is driven mainly by capital intensity and human capital, but this may not necessarily translate into export dynamism. Innovation, whether it is product or process innovation, is likely to be the key driver in exporting. Exporters are likely to be larger firms with foreign ownership. There is some evidence that trade liberalization may promote exports, but this is less relevant for innovating firms.

Impact of globalization on productivity

Chapters 4–7 examine the impact of liberalized trade and/or investment regimes on firm productivity. Chapter 4 examines the impact of trade policy changes on firm productivity in the Philippines, characterized by an incomplete liberalization process and reversal of policy in midstream. Although the Philippines implemented substantial trade reforms from the 1980s up to the mid-1990s, it adopted a selective protection policy in the early 2000s. The regression results show that among firms in the purely importable sector, trade protection is negatively associated with firm productivity. As for firms in the purely exportable sector, the evidence is weak due to the strong bias of the system of protection against exportables. The study in this chapter shows that the selective protection policy not only reversed the productivity gains from the previous liberalization, but also undermined the output restructuring from less productive to more productive firms that was already under way as the protection of selected sectors allowed inefficient firms to survive.

Chapter 5 asks whether liberalized trade and FDI have enhanced firm productivity in India. Over recent years India has witnessed wide-ranging economic reforms in its policies governing international trade and FDI flows. Consequently, both trade and FDI flows have risen dramatically since 1991. Using firm-l...