![]()

Part I

Empowering the landscape of the Buddha

![]()

1 Gaya–Bodh Gaya

The origins of a pilgrimage complex1

Matthew R. Sayers

The pilgrimage sites of Gaya and Bodh Gaya, though ostensibly sacred places for two different religions, have a long, shared history. In this chapter I examine the earliest available evidence of these two sites in order to better understand the place they held in the Indian imagination during the life of the Buddha. I intend to bring the history of the Hindu traditions of śrāddha to bear on the history of Gaya and Bodh Gaya in order to answer a deceptively simple question: Why did the Buddha choose to go to Bodh Gaya to strive for enlightenment?

Assuming the ancient fame of Gaya as a place where pilgrims went to liberate their ancestors, Fred Asher suggests, “Possibly, then, the Buddha came to the outskirts of Gaya specifically because it was the place where pilgrims sought an escape from the fetters of death—albeit on behalf of deceased relatives rather than themselves” (1988: 87; see also 2008: 1). DeCaroli accepts this view as the foundation for his reading of the narratives about the Buddha’s enlightenment (2004: 106–7) as do others (e.g., Barua 1975; Bhattacharyya 1966). These scholars presuppose that the Brahmanical association between śrāddha and Gaya predates the lifetime of the Buddha. I aim to show that this view is mistaken.

First, I address the history of śrāddha as relevant to the cultural background for this time frame and discuss the earliest references to Gaya in both Brahmanical and Buddhist sources. I hope to correct some misconceptions about the development of śrāddha in ancient India and indicate how a more nuanced view is instrumental in understanding the significance of Gaya from the time of the Buddha to the beginning of the Common Era. Specifically, an analysis of the textual materials of both traditions shows that there is no unambiguous reference to the śrāddha at Gaya until well after the Buddhist narratives of enlightenment become popular. With respect to Uruvelā (later called Bodh Gaya), I offer a different interpretation of the Pāli texts’ descriptions of the Buddha’s time there, specifically addressing his reason for going to Uruvelā to strive for enlightenment. Finally, I will synthesize this evidence and argue that the Buddha went to Uruvelā in order to distance himself from the traditional associations with Gaya, which was at the time a popular ascetics’ haunt.

I will begin with a discussion of the ancestral rites. While one can find hints of the practice of ancestor worship in the ṛg Veda, the śrāddha is not described in the ritual texts until the Gṛhyasūtras, domestic ritual manuals composed during the second half of the first millennium BCE. The older rituals, the piṇḍapitṛyajña and the pitryajha, belong to the corpus of large-scale, public Vedic ritual that dates to the second millennium BCE. The Gṛhyasūtras mark a significant moment in the history of ancestor worship in India; they codify the domestic ritual tradition that is alluded to in the older ritual literature, but finds no formal expression. References to domestic rituals in the Brāhma?as attest to a lively domestic ritual life (Gonda 1977: 547; Oldenberg 1967: 1.xv-xxii), but Oldenberg successfully demonstrates that no sustained literature on the household ritual predated the Gṛhyasūtras (Oldenberg 1967: 1.xviii). The domestic rites grew and developed during the same time frame as the śrauta rites; that is, both domestic and śrauta traditions of ancestor worship thrived within the same larger tradition. However, these two traditions are not merely recorded in the Gṛhyasūtras; these texts demonstrate an innovative spirit and evidence significant cross-pollination. The śrāddha owes a debt to Vedic ancestral ritual, but is ultimately a product of the formative stages of classical Hinduism, a transition characterized by the waning popularity of Vedic ritual and an increase in the concern with private domestic ritual.

The public śrauta and domestic gṛhya rites differ in two significant ways. First, while the Vedic ritual requires the full complement of Vedic priests, and considerable money, the śrāddha is a private ritual, performed by a householder. This made ritual accessible to a broader spectrum of religious actors and contributed to the increase in the importance of domestic ritual to Indian religious identity. Second, whereas in the piṇḍapitṛyajña offerings are made into the ritual fire, in the śrāddha the householder makes the offerings to Brahmins who stand in for and represent the Pit?s, the ancestors. The Brahmin takes on the role of mediator, enacting the exchange between householder and ancestor, supplanting Agni, the divine mediator of the Vedic ritual.

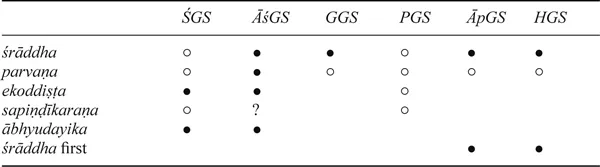

Domestic ritual certainly predates the composition of the Gṛhyasūtras, but it is clear from the evidence in those texts that the śrāddha was a relatively new phenomenon, at least in the form that survives. My argument rests on a comparison of the rituals in the different Gṛhyasūtras, seen in Table 1.1, which suggests that the conception of the śrāddha was contested—or, perhaps better, under construction—during the period of the composition of these texts. Several aspects of the descriptions of the śrāddha found in the Gṛhyasūtras support this hypothesis.

Table 1.1 Reference to different types of śrāddha in the Grhyasūtras.

Most significant in this respect is the fact that the authors do not all describe the same types of śrāddha or use the same terminology to describe the rituals they do discuss. In classical Hinduism the four types of śrāddha are: the pārvana, the monthly offerings to one’s ancestors; the ekoddiṣṭa, the ritual that sustains the preta for the first year after death; the sapiṇḍīkaraṇa, the ritual that transforms a preta into a pitṛ; and the ābhyudayika, a śrāddha that celebrates an auspicious occasion. Only one Gṛhyasūtra explicitly deals with all four types; ironically it is Sankhāyana, who fails to employ the term pārvana to describe the monthly feeding of the ancestors, the only śrāddha common to all the Gṛhyasūtras I examined. More significantly, two authors don’t even use the word śrāddha in their description of the ritual. The gradual integration of the popular rites of ancestor veneration into the Brahmanical theology, their textualization so to speak, involved some innovation and considerable contestation over the conceptualization of the ritual cycle as a whole. For the earlier Grhyasūtra authors, then, the śrāddha did not occupy as central a place in the Indian ritual life as it does for the later tradition. The ritual experts who composed the domestic ritual manuals, however, worked to change this.

The organization of the gṛhya texts evidences this effort to make the śrāddha a more central part of a ritual life. The first four authors deal with the śrāddha as a special instance of the aṣṭakā rituals, rites performed on the new moon and having a close connection to the end-of-year/new year celebrations, but āpastamba, one of the later authors, identifies the aṣṭakā as a special case of the śrāddha. Understanding the conception of ancestor worship in the period under discussion requires a discussion of the transition from ancestor worship occurring on one of the aṣṭakā days to the aṣṭakā being but one form of the śrāddha. By the time of āpastamba śrāddha had become the paradigm for ancestor worship, but this formulation of the śrāddha, which is so consistent in classical Hindu texts, is still under construction in the Grhyasūtras.

Central to this particular innovation in the conceptualization of ancestor worship is the conception of the aṣṭakā. W. Caland (1893), who wrote the definitive work on ancestor worship in India, operates on the assumption that the aṣṭakā are ancestral rites, but at least one scholar besides myself has called that into question. M. Winternitz suggests that the character of the aṣṭakās in the earlier Grhyasūtras is ambiguous and suggests that Caland treats the aṣṭakās as ancestral rites based on “the fact that so many ceremonies and mantras related to the Manes occur in the Ashtakâ rites” (1890: 205). This is clearly anachronistic reasoning, which is, unfortunately, all too common in studies of ancestor worship in India.

The older2 Grhyasūtras consider only one of the three aṣṭakās unambiguously dedicated to the ancestors (Winternitz 1890: 205). For example, Asvalāyana, whom I place in the earlier group, indicates that there is some debate over the object of veneration for the aṣṭakā. “This (Ashtakâ) some state to be sacred to the Viçve devâs, some to Agni, some to the Sun, some to Pragâpati, some state that the Night is its deity, some that the Nakshatras are, some that the Seasons are, some that the Fathers are, some that cattle is” (āśGS 2.4.12, Oldenberg 1967).

While there is no way to pin down specific lines of influence or to understand the absolute chronology of these developments, the contested nature of these rites is suggestive. The popular domestic rites, previously untextualized, gradually integrated into the Brahmanical tradition during the composition of the Grhyasūtras, may very well have always been done at this time of year, but we cannot tell with any certainty. It is clear, however, that the Brahmanical tradition did not make this association unambiguously before the third century BCE.3

By the time of the Dharmasūtras, the śrāddha is conceived of in a consistent fashion and is firmly entrenched as a key aspect of the householder’s dharma. Additionally, the Arthaśāstra supports the impression that the śrāddha was a common part of religious life in ancient India by the beginning of the Common Era. The phrase daivata-upahāra-śrāddha-prahavaña, offerings to gods, ancestral rites, and festivals, suggests ancestral rites are a part of the author’s conception of regular religious activities (Aś 3.20.16). Thus, it is not until the beginning of the Common Era that we can understand the śrāddha as either a common religious practice or central to the Brahmanical self-conception.

Now let us consider the Buddhist materials on śrāddha. In the Jāṇussoṇisutta of the Aṇguttara Nikāya, Jāṇussoṇi approaches the Buddha and asks whether offerings he makes in the saddhas (Pāli for śrāddha) actually benefit his ancestors (A 5.269). The Buddha takes the opportunity to expound upon the behaviour, good and bad, that leads to the many different realms of rebirth, and concludes that the offerings made in the saddha, intended as they are for the deceased relatives, will reach those in the petti-visaya. In the end, Jāṇussoṇi praises the Buddha and the Buddha affirms the efficacy of the śrāddha and assures Jāṇussoṇi that his gift will be fruitful for him (A 5.273).

From this clear example of śrāddha in a Buddhist context, we turn to a later practice that evidences a cultural memory of śrāddha. The Petavatthu, literally Ghost Stories, offers many examples of offering made to petas, ghosts, often relatives. This collection of stories aims to illustrate the fate of those who fail to make religious gifts during their life.

The tale entitled “The Ghosts Outside the Walls” (Pv 1.5) exemplifies the memory alluded to above. A king presents a ritual meal to the Buddha while his deceased ancestors, now ghosts, watch on. To their dismay the king fails to dedicate the meal to them. In grief the ghosts roam about the king’s home wailing and making terrifying noises. The Buddha, through his supernatural insight, understands and explains the situation. The king immediately invites the Buddha to a second meal the next day. Tha...