![]()

Section 1

How education is understood in different cultures

Introduction

Hugh Lauder

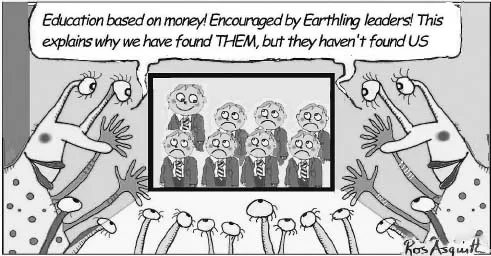

(Cartoon by Ros Asquith)

This section raises fundamental questions about the nature of education and educational change. Developing a comparative understanding of the similarities and differences in education, teaching and the curriculum in national cultures enables us to reflect upon the assumptions we make about:

• the purposes of education;

• the nature of teaching and the curriculum;

• the way we think about the learner;

• the global forces that bring about convergence and divergences in educational systems.

By examining the assumptions we make about education we can take a first step in asking whether our educational practices are justified. This is a first step because it enables us to be reflective and critical about our role as educators. The second step is to ask whether there are better ways of engaging in teaching and learning. But this step needs to be informed by the forms of thought that structure our understanding as well as the political, social and economic interests that influence our practice.

A consideration of these factors enables us to identify not only the assumptions we make about our educational practices but the limits and possibilities for change.

Alexander’s chapter exemplifies these issues. He is concerned with pedagogy, by which he means not only the acts of teaching but also the thinking behind the decisions we make in teaching and our justifications for them. Pedagogy, in his view, is an intellectual as well as technical practice. His paper opens by asking why it is that the question of a comparative pedagogy has been ignored in Britain, although the neglect of a sophisticated comparative pedagogy is largely true of all Anglo-Saxon intellectual educational traditions. In part, the answer to this question is that an adequate framework for understanding pedagogy has not previously been developed. However, in this paper Alexander develops a model for the comparative analysis of pedagogy which he argues can be seen as being influenced by three levels: the classroom; the educational system and related policies; and culture and the self – the role played by values and the way they influence the construction of teaching acts.

As well as a model for comparative analysis this framework allows teachers to think through the assumptions and justifications they make in their own practice. Here the questions that this model prompts are:

• What view of the learner do I take?

• How does education relate to society?

• Which levels are most important in influencing my practice?

The paper by Roger Dale raises the equally profound question of whether there are aspects of globalisation and the modern age (modernity) which create pressure towards convergence in pedagogy and the curriculum in developed and developing nations. Alexander’s comparative analysis points in the direction of significant differences in the assumptions underlying pedagogy in different countries, but that does not mean that there are forces external to the views of teachers which are influencing the nature and structure of pedagogy. Dale seeks to tease out the various factors that make for convergence and divergence by critically examining a leading theory on education and globalisation, ‘world polity’ theory, which explains convergence on the basis of a common set of universal values, drawing on Western modernity, that now permeate education systems at a global level. The central argument of this theory is that there is a supranational ideology of modernity which has determined similarities in the curriculum across most countries. As Dale notes, ‘At the core of [this ideology] lies “rational” discourse on how the socialisation of children in various subject areas is linked to the self-realisation of the individual and, ultimately, to the construction of an ideal society.’

The significance of this view is that it addresses one of the fundamental questions in education: what should be taught? It is a question that resurfaces in many of the papers in this book (see Young and Nash). But the answer given by the world polity theorists is paradoxical: on the one hand they argue that the curriculum is imposed by this modernist ideology, irrespective of whether it actually addresses a country’s needs, while on the other they see it as part of a rational discourse that can enable self-realisation, which presupposes a degree of individual freedom.

Anna Sfard’s paper comes at the fundamental questions concerning education from a different angle. Her paper is concerned with the way we think and talk about education. She notes that much of our discussion about education is impregnated with metaphors. For example, she notes three uses of metaphorical language that we typically take for granted in education: the idea that students construct their knowledge, that they may have learning disabilities and that, as teachers, we seek to give students better access to knowledge. There are more subtle examples, the more obvious being associated with metaphors of growth. We think of children growing not only physically but psychologically and talk about them reaching their potential, as if there is some kind of ideal end state that we are aiming for. Why do we use metaphors? Her answer is that it enables us to develop knowledge but they also shape our thinking and our actions. The problem is one of judging how apt and thereby useful any given metaphor in education may be. In turn if our knowledge claims are impregnated with metaphors then how certain are our knowledge claims about pedagogy? Different answers are given in chapters of this book. For example, David Hopkins is confident that the system of pedagogy and assessment used in England has created improvements in educational outcomes as measured by tests. By the same token, similar state-mandated pedagogies in the United States may be considered to have also created improvements. But the chapters by Torrance and Robinson, in different ways, contest the basis for such confidence.

What is clear from these chapters is that education, and pedagogy in particular, is an irreducibly intellectual project. It requires comparative analysis, which in turn can illuminate philosophical and theoretical insights across the disciplines of psychology and sociology and related empirical research. In these respects the idea that pedagogy is just about teaching techniques, a view that is taken by some policy-makers, is fundamentally misguided as the issues raised by the chapters in this book demonstrate.

![]()

1.1 Pedagogy, culture and the power of comparison

Robin Alexander

Introduction

This chapter asks why pedagogy, which is at the heart of the educational enterprise, has been largely ignored in British comparative enquiry. Pedagogy is defined as ‘the observable act of teaching, together with its attendant discourse of educational theories, values, evidence and justifications’. This definition opens the window to a comparative analysis which focuses on pedagogy as ideas which enable teaching in the classroom, formalise it as policy and locate it in culture. By this process a genuine comparative analysis of pedagogy is made possible which can distinguish the universal in pedagogy – its various acts, frames and form – from the culturally specific ways that these are applied. For teachers, one advantage of such an approach is that it enables critical reflection on what may seem to them as the ‘natural’ or given way of teaching. It also brings to the fore the sometimes unexamined values by which their practice is informed.

The neglect of pedagogy in comparative enquiry

Pedagogy is the most startlingly prominent of the educational themes that British comparativists have ignored. In the millennial issue of the UK journal Comparative Education, Little noted just 6.1 per cent of the journal’s articles between 1977 and 1998 dealt with ‘curricular content and the learner’s experience’ as compared with nearly 31 per cent on themes such as educational reform and development (Little, 2000, p. 283); Cowen asserted that ‘we are nowhere near coming fully to grips with the themes of curriculum, pedagogic styles and evaluation as powerful message systems which form identities in specific educational sites’ (Cowen, 2000, p. 340); and Broadfoot argued that future comparative studies of education should place much greater emphasis ‘on the process of learning itself rather than, as at present, on the organisation and provision of education’ (Broadfoot, 2000, p. 368).

If the omission is so obvious, one might ask why comparativists have not remedied it. There may be a simple practical explanation. Policy analysis, especially when it is grounded in documentation rather than fieldwork, is a cheaper, speedier and altogether more comfortable option than classroom research. As a less uncharitable possibility, but echoing Brian Simon’s ‘Why no pedagogy in England?’ (Simon, 1981), we might suggest that a country without an indigenous ‘science of teaching’ is hardly likely to nurture pedagogical comparison: cherry-picking and policy borrowing maybe, but not serious comparative enquiry (Alexander, 1996).

Or perhaps pedagogy is one of those aspects of comparative education which demands expertise over and above knowledge of the countries compared, their cultures, systems and policies. I rather think it is, especially given the condition which Simon identified. One can hardly study comparative law or literature without knowing at least as much about law or literature as about the countries and cultures involved and about the business of making comparisons; the same goes for comparative education. Pedagogy is a complex field of practice, theory and research in its own right. The challenge of comparative pedagogy is to marry the study of education elsewhere with the study of teaching and learning in a way that respects both of these fields of enquiry yet also creates something which is more than the sum of their parts.

New territories, but old maps

Little’s framework for mapping the literature of comparative education, referred to above, differentiated context (the country or countries studied), content (a list of thirteen possible themes), and comparison (the number of countries compared). Trying to place my Culture and Pedagogy (Alexander, 2001) within this framework underlines pedagogy’s marginal status in mainstream comparative discourse. This study used documentary, interview, observational, video and photographic data collected at the levels of system, school and classroom. The study’s ‘context’ was England, France, India, Russia and the United States. Its ‘comparison’ was across five countries (a rarity). However, its ‘content’ straddled at least six of Little’s thirteen themes without sitting comfortably within any of them, and the educational phase with which it dealt – primary education – did not appear at all in that framework (nor, strikingly, did the terms ‘teaching’ or ‘learning’, let alone ‘culture’ or ‘pedagogy’).

There is a further reason why the content of this research maps so imperfectly onto Little’s framework: the latter does not accommodate studies that cross the boundaries of macro and micro. Culture and Pedagogy – as the title suggests – acknowledges Sadler’s hoary maxim that ‘the things outside the school matter more than the things inside … and govern and interpret the things inside’ (Sadler, 1900), yet Little’s framework implies the need for singularity – national or local, policy or practice, the system or the classroom – rather than dialectic. In this respect, comparativists may be somewhat behind the larger social science game, in which the relationship between social structure, culture and human agency has been ‘at the heart of sociological theorising’ for well over a century (Archer, 2000, p. 1).

Pedagogy does not begin and end in the classroom. It is comprehended only once one locates practice within the concentric circles of local and national, and of classroom, school, system and state, and only if one steers constantly back and forth between these, exploring the way in which what teachers and students do in classrooms reflects the values of the wider society.

That was one of the challenges which Culture and Pedagogy sought to address. Another was to engage with the interface between present and past, to enact the principle that if one is to understand anything about education elsewhere one’s perspective should be informed by history. So while the comparative journey in Culture and Pedagogy culminates in an examination of teacher–pupil discourse – for language is at once a powerful tool of human learning and the quintessential expression of culture and identity – it starts with accounts of the historical roots and developments of primary education in each of the five countries, paying particular attention to the emergence of those core and abiding values, traditions and habits which shape, enable and constrain pedagogical development.

Defining pedagogy: the shifting sands of educational terminology

So far a definition of pedagogy has been implied. It is time to be more explicit, though only after sounding a warning about terminology, for one of the values of comparativism is that it alerts one to the way that the apparently bedrock terms in educational discourse are nothing of the sort.

Thus it may well matter, in the context of the strong investment in citizenship which is part of French public education, that éduquer means to bring up as well as formally to educate and that bien éduqué means well brought-up or well-mannered rather than well schooled (‘educate’ in English has both senses too, but the latter now predominates); or that the root of the Russian word for education, obrazovanie, means ‘form’ or ‘image’ rather than, as in our Latinate version, a ‘leading out’; or that obrazovanie is inseparable from vospitanie, an idea which has no equivalent in English because it combines personal development, private and public morality, and civic commitment, while in England these tend to be treated as separate and even conflicting domains; or that obuchenie, which is usually translated as teacher-led ‘instruction,’ signals learning as well as teaching. It is almost certainly significant that in English (and American) education ‘development’ is viewed as a physiological and psychological process which takes place...