- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Development in East Asia

About this book

First published in 1967, this influential study reviews the economic development of 15 countries from East Asia in the period between 1945 and 1965. It deals with a wide variety of factors influencing the development of the region, including the influence of foreign governments (both international aid and foreign trade); population development; industrialisation; transport and communication infrastructure; and the impact of economic development upon the population of East Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic Development in East Asia by E. Stuart Kirby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

ASIAN PERSPECTIVES

DIFFUSE DEVELOPMENT

Asian development involves one half of the world’s population, and all the problems on which the future of the human race may depend. Generalizations and theories must be regarded with extreme caution; the countries are so different that aggregation is usually difficult and often misleading.

Civilization is older in Asia than in Europe; yet the Asian countries and regions have developed much more separately than the European, with far less of a common basis. In Europe there were continuous juxtapositions, fusions or overlaps – besides positive movements, even deliberate efforts at comprehensive acculturation – which have brought its twenty-odd nations so closely together that their combination in one political, social and economic unit now has its advocates.

Our fifteen Asian countries have not been subject – until very recently – to any such consolidating influences or pressures. They have developed along their own paths, with no cultural or economic fusion. This is not only because they differ much more strikingly than do the Western countries in soil, climate, race, religion, culture, resources and other parameters; it is due also to physical features creating objective as well as subjective barriers, not only between one Asian country and another but between parts of a single country. The separation may be by great deserts (such as those east of India and northwest of China), gigantic mountains (such as those of the Himalayas, Tibet or North Korea), impenetrable jungles (as between Burma, India, Thailand, Indochina and Malaysia), great rivers (such as the Mekong), or wide and stormy waters (such as the China Seas).

Some strong movements overswept these barriers : the military Pan-Asian conquests of the Mongols, the eastwards expansion of Buddhism from India, the persistent caravan trade across north-central Asia, the seafaring of the Arabs and others. Nevertheless, regionally-unifying influences came only recently, with the incursion of the Westerners. An Ancient Greek maxim is fulfilled most powerfully in Asia. The land has divided, more drastically than in the Mediterranean area; while the sea has united, it has done so only sporadically. Through long ages the East Asian countries communicated and traded relatively little with each other; at present they still traffic distinctly less among themselves than with other countries and regions of the world.1

ECONOMIC DEPENDENCE ON THE WEST

World maps illustrating the flow of goods or shipping – or of funds, persons, ideas or any other factor in human development-would show extremely heavy concentration in and around the North Atlantic, with less density in the Mediterranean, dwindling increasingly East of Suez; reviving only as Japan is approached, but thinning again over the Pacific. Off this main artery, the subsidiary inter-Asian links are very slender. Even the feeder-lines are not heavy; South and South-East Asian countries deal for the most part directly with industrialized countries.2

Moreover, the unevenness is distinctly increasing; though world trade and Asian trade have greatly expanded in recent times, the proportions between these flow-lines have become more divergent. East Asia’s trade and shipping relations with the developed countries multiply and thicken distinctly more than do those within East Asia itself, especially those between its underdeveloped countries.

The first law of economic development in East Asia has from the outset been that water transport is cheaper (and usually easier) than land transport. This was vividly instanced in 1945-6 by the case of UNRRA supplies to China. The net cost of transporting these a mere 20-200 miles overland for the last stage of their journey in China was – quite apart from bribery and malfeasances – much higher than that of some 7,000 miles of sea carriage from the ports in the USA.

The distances involved are prodigious; for example, Tokyo is about as far from Shanghai as London from Gibraltar, Peking is roughly the same distance from Canton, the length and breadth of India about the same expanse. The distance from Singapore to Tokyo is about the width of the Atlantic from England to Canada. The distance from Singapore to Bombay is less; it is about the length of the whole Mediterranean. China is roughly the size of the United States, India and Pakistan similar in extent to Western Europe.

While ‘colonialism’ has largely disappeared in the first two post-war decades, in the economic aspects especially there is increasingly real dependence on the developed countries. Material and ideological considerations, subjective and objective reactions are widely mixed; they must be discussed together.

COLONIALISM

The basis for the direly needed and ardently desired economic development was formed in the era of Western colonialism; with lasting influence, though the colonial period was really short (in East Asia relevantly about 1845-1945). It is as necessary as it is difficult to judge objectively how far the outcome was affected by the scale, extent and depth of penetration of Western Colonialism on the one hand – which may easily be exaggerated in some propagandistic or emotive responses – and what was on the other hand inevitable for geographical, intrinsic or endogenous reasons.

The classic Marxist-Leninist formulation saw the colonialists’ aim as securing raw materials and markets for their own manufactures: as an offshoot and extension of the Industrial Revolution. Philanthropic, intellectual or adventurist motivations were minor, from the point of view of economic development. Political or social changes were not pressed by the colonialists; rather they patronized and confirmed in power native rulers, feudal monopolists, indigenous vested interests, even Oriental despots, using rather than recasting the societies they found, they ‘froze’ the basic social structures and economic arrangements at some pre-modern stage of the latters’ evolution.

The original and proper sense of ‘colony’ is a settlement abroad of populations from a homeland. In Asia, Western settlers were relatively few and did not form considerable groups. Certain ‘enclaves’ were sharply noticeable : mining or plantation areas, reproducing microcosmically the homeland conditions for the ‘expatriates’, were equipped from the metropolitan country, returned dividends and senior staff there. They were strikingly separate from the economy of the colony, being rather extensions of the home country. Less blatantly ‘apart’ were the white communities in the capital, port and market cities – economically at least – though they persisted in their social or caste barriers.

ASIA AMONG THE UNDERDEVELOPED REGIONS

Many comparisons are drawn between the developing Asian countries and the developed countries. Comparisons with the non-Asian underdeveloped areas are, however, also instructive. Table 1.1 shows broadly the share the developing countries of East Asia have in the total, not of the world’s, but of all the underdeveloped countries’ population, area, national income, international trade and American aid, in comparison with those in the other regions.

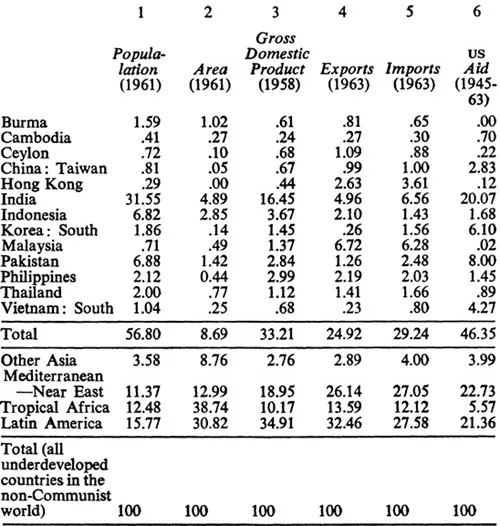

Table 1.1. The East Asian developing region’s ranking in the underdeveloped world3

Percentage of total (Non-Communist) developing countries’ :

It is seen that these thirteen countries have just over half the total population of all developing countries in the world, only one-twelfth of their area, one-third of their income, a little over a quarter of their trade and nearly half of the American aid.

Per person the region as a whole has distinctly the least share of land area, income and trade of any underdeveloped area, and the least share of American aid (except tropical Africa) among the five regions. The differences are striking; e.g. the high position of Malaya and Hong Kong in trade and income and the comparatively high per capita incidence of aid in certain countries (though the absolute amounts per person, spread over the large total populations concerned, are, of course, relatively small). On the per capita basis the East Asian developing countries are in fact the world’s poorest region.

WAR AND LIBERATION

Nineteenth-century colonialism inscribed on its banners ‘Law and Order’. It introduced the world economy and the modern age to an East Asia little prepared for or inclined to such a development. Only in Japan was there a national, wide, purposeful and prompt response to this challenge. Elsewhere fatalism, apathy or quietism were widely and generally the characteristic Asian moods, often with some disdain of foreign materialism. Colonialism spread over the surface of this hemisphere, seizing its key points, but remained an external mould; it did not largely reshape or replace the inner foundations of the local social and economic structures. Modern nationalism did not become strong in Asia until the 1930s – and not strong enough to take power until 1945-50, when the framework of the older order lay shattered, mainly by forces quite other than internal nationalistic pressures.

It was the Second World War that disintegrated the old order, ravaging the economies, societies and policies of this whole Region so widely and deeply as to inaugurate a diametrically different era. Diverse and complex nationalisms, avidity for modernization, an intense and immediate desire for economic and technical progress, are the present traits.

The war was made by the Japanese militarists, paralleling the motives and methods of their allies the German Nazis and Italian Fascists. The Japanese had harried China since 1894. In 1931 they occupied Manchuria; and in 1937-8 all but the remote interior of China. At the end of 1941 and early in 1942, they swiftly occupied the Philippines, Indonesia, Indochina, Malaysia, Thailand and Burma. This whole Japanese-occupied area was declared to be the ‘Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere’ : with, for the first (and so far the only) time, a grandiose and comprehensive scheme for the integral economic development of the whole Region. Like the greater Nazi Reich, the development was to be on neo-pan-colonial or supracolonial lines, with Japan as the great industrial centre, supplied from this empire and finding its markets there.

Japan’s economic warfare failed, almost as rapidly as its military Blitzkrieg had succeeded. The Coprosphere (as it was at once dubbed by Western propagandists with a classical education) immediately fell into two parts; an Inner Zone (Japan, Korea, East and South China, Formosa) and an Outer Zone (the rest). In 1942-3 Allied counter-attacks by sea, air and land brought transport in the Outer Zone very largely to a standstill; beginning the process of attrition whereby industrial Japan was very effectively blockaded. In 1944-5, the process was inexorably pushed into the Inner Zone, right up to Japan itself. Virtually all Japanese shipping was sunk. The twenty-four main cities of Japan and innumerable other targets were heavily bombed, with effects fully comparable to those in Germany, before the atomic bombs were released.

In the whole Region economic life was severely vitiated and extremely fragmented. Not merely each country but every district and locality had to fall back on the simplest and most dire self-sufficiency. People raised vegetables or inferior subsistence foods such as cassava. Wooden boats were built for the limited fishing or transportation. Hundreds of millions of Asians led improvised existences. The Japanese largely removed domestic and general stocks and fittings, as well as industrial equipment and supplies, to Japan. Hardly any replacements or maintenance were possible. The whole area fell into such dilapidation and decrepitude as was not seen in Occupied West Europe.

India, Pakistan and Ceylon on the Allied side were not overrun and not subject to these conditions. Their trade and industrialization in fact developed substantially during the war, but under various strains, especially the overloading of transport, organization and other facilities and the lack of normal peacetime maintenance.

In 1946-7 rationing and improvisation generally continued. Nowhere in the world were normal supplies available except in America. Overall shipping and feeding arrangements were made by the Allied Reoccupation authorities.

The Japanese fostered Asian nationalist groups or movements, by their own lights and for their own purposes, in their occupied territories (including an Indian movement). Broader Asian nationalist parties and organizations sprang up everywhere in strength. The days of foreign rule were numbered. Political clashes, civil and race strife followed in the whole Region.

Post-war East Asia was in extreme distress, penury and dislocation. It is necessary to note the nadir from which East Asia is now – parlously but substantively – rising into full development. The present resurgence started in large part from zero levels, at a time of abnormal difficulties. Indices based on the immediate post-war years may be misleading if this is not considered. In the extreme instance Communist China emitted abundant propaganda in terms of very large percentage increases over 1949; which is in perspective only if it is realized that 1949 did not represent ‘par’, but the conditions of extreme depression, standstill and disorder.

NATIONALISM AND DEVELOPMENT

The subsequent course has been nationalist, with the following salient aspects. The economic and social focus has been on industrialization. The political focus has been on a midway course, professing neutrality between systems. Blaming ‘colonialism’ for all difficulties is probably no more – but no less – significant than the ascription by naive socialists of all evils on ‘capitalism’. The state has however been the means, and planning the method, of evolution in the desired direction. This was inevitable. There was no other group able to undertake the tasks. Moreover, only the state could be ostensibly above the conflicts of interest which are necessarily involved.

The universal drive for industrialization was conditioned in Asia by the circumstances of the epoch of the Second World War. Iron and steel appeared to be the solid basis of the affluent society; guns, tanks, shells and battleships the means of national security and power. Heavy industry was given all priority, in the belief that its development would underlie and bring forward every other kind of development. This was the reasoning of non-Marxists, as well as Marxists; but the influence of Soviet Russia was important in this connection. Russia had achieved a significant industrialization and modernization, from a similar state of backwardness, by putting heavy industry first. The fact that it had dealt ruthlessly, both in this and in the agrarian sector, tended at first to be somewhat overlooked.

During the 1950s however, the real and social costs of Russia’s industrialization came to be widely realized. Critical and general books on contemporary totalitarianism were certainly more widely read in Asia than such works as Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. At the same time the USSR’S development took a new high road, joining the post-industrialized advanced countries, displaying a certain embourgeoisement and placing itself in the higher category of nuclear and space technology.

China has taken over the banner of Asian-style Communist development which the Russians raised in the 1920s; but its success and its relevance as a model for Asian development are uncertain, while its military and political initiatives in and against developing countries such as India, Indonesia, Korea and those of S.E. Asia have not given it the image of an Asian partner.

The political vicissitudes may in the long run be of minor and transient importance compared to the technological evolution and realization of its implications. Advanced modern techniques are now the real focus of interest. It is understood that ‘resources’ are entirely relative to techniques; even if the resources are limited, continued rapid technical progress makes even constant resources more extensively and efficiently usable.

Politically the Maoist call to Asians to ‘struggle’, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1. Asian Perspectives

- 2. Population Pressure

- 3. Food Shortage

- 4. Foreign Trade

- 5. The Raw Material Base

- 6. Industrialization

- 7. Transport and Communications

- 8. National Budgets

- 9. Economic Planning

- 10. International Aid

- 11. The Results for the Asians

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Index