![]()

Chapter 1

The Economic Development of Germany, 1870–1914

The Dimensions of the Problem

Short-Term Growth Fluctuations

The Development of German Industry

– Iron and Steel – Coal – Textiles

– Chemicals – The Electrical Industry

– Engineering – Conclusion

Transport

Population and Urbanisation

Capital Management

– Banking – The ‘New Capitalism’

Agriculture

Germany and the International Economy

– International Trade – Foreign Investment

Conclusions

A Note on the Economic Development of Luxembourg

Suggested Reading

Notes

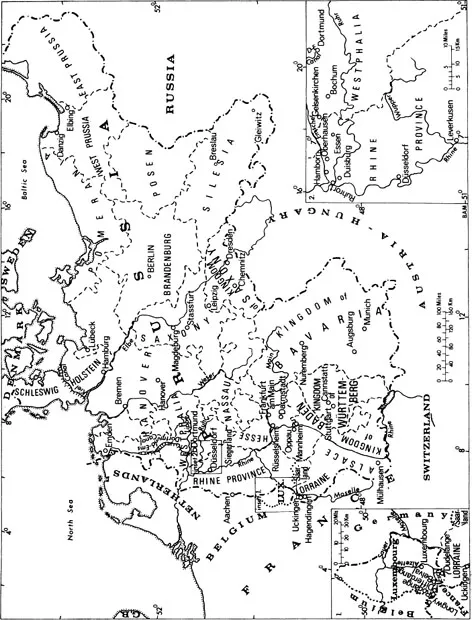

THE DIMENSIONS OF THE PROBLEM

The economic history of continental Europe after 1870 was dominated by the persistent growth and development of the German economy, so that by 1914 Germany had displaced France as the most powerful of the continental economies and had attained a level of per capita income probably slightly higher than the French. To contemporaries this seemed the most outstanding fact of the period and viewed in retrospect it is still a phenomenon that should command the respect of the historian. The changes in central Europe which laid the foundation of this remarkable development were described in our previous work.1 That a disunited collection of agricultural territories in 1830 could by 1913 have become the symbol of what seemed a new form of European society in the making is the strongest evidence of the daunting capacity of economic change to alter rapidly the course of history and of human society. It would be too bold to pretend to offer complete explanations. There is still much research to be done on questions of vital importance and without this explanations of the phenomenon will remain in several respects incomplete.

The dimensions of the phenomenon give some indication of how complex the explanations will be. The mean annual rate of growth of net domestic product between 1850 and 1913 was 2–6 per cent. As we shall see there were marked short- and medium-term fluctuations in this rate of growth. After 1873 there was a period of comparative stagnation, whereas in the European industrialisation boom after 1896 net domestic product increased at an annual average rate of 3.1 per cent a year until 1913. But the picture is still one of much more persistent growth than in France or Britain. The contribution of the different sectors to that growth was also more even. The output of the industrial sector increased by 3.8 per cent annually over the period 1850–1914, of commerce, banking and insurance by 3.2 per cent, and of agriculture by 1.6 per cent. The share of industry and services in the composition of net domestic product grew and that of agriculture fell until by 1913 the agricultural sector was contributing less than one-quarter (see Table 1).

Table 1 Structure of net domestic product in Germany, 1870–1913 (at 1913 prices

Period | Agriculture, forestry and fisheries (%) | Industry, handicrafts and mines (%) | Transport and services (%) |

1870–4 | 37.9 | 31.7 | 30.5 |

1880–4 | 36.2 | 32.5 | 31.3 |

1890–4 | 32.2 | 36.8 | 31.0 |

1900–4 | 29.0 | 39.8 | 31.2 |

1910–13 | 23.4 | 44.6 | 32.0 |

Source: W. G. Hoffmann, Das Wachstum der deutsehen Wirtschaft seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Berlin, 1965), p. 33.

One consequence was that the physical volume of output in many important areas surpassed that in France and Britain although those countries had begun much earlier on the path of rapid industrialisation. With an annual average production of steel in 1910–13 of 16.2 million tons Germany was making at least two-thirds of all Europe's output. With an output of electric power in 1913 of 8,000 million kilowatt hours she was producing 20 per cent more electrical energy than Britain, France and Italy combined. In certain modern industries, engineering and organic chemicals in particular, the value of her output and the level of her technology were higher than in other European economies. Between 1910 and 1913, when the annual average quantity of coal and lignite mined was 247.5 million tons, she was mining well over half the quantity mined on the continent. The second consequence was a noticeable increase in real incomes for the population as a whole in spite of a rapid growth in numbers. Real wages in industrial employment doubled after 1871. The real wages of those employed in the agricultural sector did not increase so rapidly, but with the shift towards industrial employment there was still a large increase in spendable consumer incomes. This was reflected in the growth of the textile and other consumer industries whose role in the initial stages of economic transformation had been less significant than in the countries further west. There were 11.2 million cotton spindles in 1913, the biggest cotton industry on the continent, and the annual raw cotton consumption of 435,000 tons was almost twice as high as in France.

Table 2 Proportion of employed persons in different sectors of the German economy, 1878–1913

Period | Agriculture, fisheries and forestry (%) | Industry, handicrafts and mines (%) | Transport, trade and public services (%) |

1878–9 | 49.1 | 29.1 | 14.1 |

1890–4 | 42.6 | 34.2 | 16.5 |

1900–4 | 38.0 | 36.8 | 19.4 |

1910–13 | 35.1 | 37.9 | 21.8 |

Source: W. G. Hoffmann, Das Wachstum der deutschen Wirtschaft seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Berlin, 1965), p. 35. The figures for domestic service are omitted.

To some extent the physical size of output reflected the greater availability of factors of production. The labour force grew much more rapidly, for example, than in France. In spite of the high rate of emigration the population increased by 24.1 million between 1871 and 1911 so that by the First World War Germany was by a great margin the second most populous country in Europe. But the labour force is estimated only to have doubled between 1850 and 1913. The productivity of labour increased over the same period at an annual average rate of 1.5 per cent so that much of the growth in output and incomes was also accounted for by changes in production methods. Therein lies a considerable part of the explanation of what happened and the figures for size of physical output are given only to show how the balance of economic power in Europe was transformed.

As everywhere, the main aspect of this sustained improvement in the productivity of labour was the increase in the share of the labour force working in industry and services. The extent of this movement is shown in Table 2. But it will also appear later that there were smaller but substantial improvements in the productivity of the labour that remained in the agricultural sector of the economy and these also contributed more to the growth of the economy than in the other large continental economies. Compared to Britain both the absolute numbers and the proportion of people working in agriculture by 1913 were still high and by most conventional measurements of the level of economic development Germany could be considered less advanced than some of the smaller European economies. Even in some industrial fields it could be argued that Germany remained more backward than France. In trying to explain the growth of productivity and the growth of the economy in a more detailed and comprehensible way we shall, however, be concentrating on those aspects in which the German economy was technologically more advanced. This is not misleading for many of the explanations of the phenomenon we are faced with are to be found in the interrelationships of technology and industry. It will often be necessary to pay as much attention to smaller industries where these interrelationships were most present as to the large cotton industry, for example, whose growth was more easily understandable in terms of the rise of consumer incomes generated by changes elsewhere in the economy.

SHORT-TERM GROWTH FLUCTUATIONS

The creation of the German Empire was a period of remarkable prosperity. A boom beginning in 1869 triggered by railway investment was only briefly interrupted by the heavy doubts cast by the war against France in 1870. In that year itself the net domestic product did not grow. But the triumphant conclusion of the war quickly restored the climate of confidence. The war indemnity paid by France, one-third of German national income in 1870, stimulated a burst of intra-European trade and a spate of company foundations on the German stock exchanges. In spite of the stagnation of 1870, net domestic product (at 1913 prices) grew in the quinquennium 1870–4 at an annual average rate of 4.6 per cent. These were the so-called Griinderjahre, the foundation years, of the Empire. The investments of 1869 bore fruit in 1870 when 1,500 kilometres of railway were completed, the biggest annual rate of increase to the system yet achieved, and one which brought about a response in the iron and coal industries even before the wave of business confidence which followed the victories in France. In 1871 207 joint stock companies were floated compared to the 295 floated over the whole period 1851–70 and in 1872 the number of new floatations rose to 479. The consumption of pig iron rose from 1.8 million tons in 1871 to 2.95 million tons in 1873 and hard coal output over the same period from 29.4 million tons to 36.4 million tons. The textile industries had less of a share in this burst of prosperity, which mainly affected, as it had in the investment boom of the 1850s, the railway, iron, coal and engineering industries.

By mid-1873 the boom had turned into a structure of risky financial speculations on the Berlin stock exchange as business conditions in the United States and Britain worsened. The financial crash in Vienna2 spread to Berlin producing a spate of bankruptcies and by the end of the year the great boom had turned into the Gründerkrise, the foundation crisis. No year in the century has had to bear such a colossal load of vague economic and social interpretation as 1873. In Britain it was for long regarded as the start of the mythical ‘Great Depression’. In Germany it has been interpreted as the year in which the liberal hopes which accompanied the foundation of the Empire were snuffed out by a long period of hard times; as the grand climacteric of the century leading to a protectionist, illiberal, highly cartelised, bureaucratised, internally uncompetitive and externally aggressive economy and society. In fact almost every way in which the evolution of the German economy and society differed from the ‘western’ model has been blamed at some time or other on the economic events of 1873. What actually happened ?

The fall in production was quite small. Pig iron production fell from 2.2 million tons in 1873 to 1.9 million tons in 1874 and coal output from 36.4 million tons to 35.9 million tons. The very imperfect indicators we have for cotton cloth suggest that output may have fallen by less than 5 per cent. Railway construction continued unchecked at the high levels it had reached in 1870; in fact 1874 set another record for the total length added to the system and in 1875 this was eclipsed again by the 2,436 kilometres added in that year. Domestic demand for iron and coal therefore did not continue to sink after 1874. But foreign demand was very low and this prevented any complete recovery. The consumer goods industries were less buoyant and output of textiles continued to fall after 1874. Mottek's recalculation of Spiethoff's earlier figures suggests that a rough hypothetical index of industrial production based on 1872–3 as 100 would show a figure of 95 for 1874–5.3 The dismayed clamour from contemporaries was mainly attributable, as in Britain, to the fact that 1873 ushered in a long period of falling prices.

But if the actual depth of the slump has been exaggerated its length has not and it was this which really made it the greatest crisis of the German economy in this period. The few reliable figures available suggest that only in 1880 did industrial production again achieve its levels of 1872–3. This was the first severe check to the rapid industrialisation of the economy since the boom of 1852. Over the period 1875–80 net domestic product did not grow. The psychological effects of this prolonged stagnation were certainly profound, but almost all the social and economic consequences attributed to these events can be more accurately explained in other ways. The 1880s in Germany were sharply distinguished from the same decade in France and Britain by being a period of growth and prosperity, particularly after 1886. There is no way in which the term ‘Great Depression’ can have any meaning when applied to Germany after 1880. The overall growth rate of domestic product in the decade was 2.5 per cent and it was in this very decade that the die was cast decisively for the future shape of the European economy. Investment flowed into new industries and technologies in Germany while investors in Britain, France and Austria-Hungary followed a more cautious path. Whereas in the period 1870–5 only 10.6 per cent of total net investment flowed into industry, in the decade of the 1880s 41.4 per cent did so. In fact the decade marks a decisive break in the long-run pattern of investment. From the start of the railway boom in 1851 railway investment had on average accounted for almost one-fifth of total investment and in the 1870s, when it had sustained the economy in bad times, had reached higher proportions. From 1880 it seldom reached even one-tenth o...