![]()

Part I

Genealogy of the reading girl

![]()

1 The genealogy of hirahira

Liminality and the girl

Honda Masuko

Translated by Tomoko Aoyama and Barbara Hartley

Prologue

Ribbon bows dance in the breeze, large butterflies upon the frills and lace that ripple about collars and cuffs. Accompanying this vision are a series of words: “Louis Quatorze,” “Rokumeikan,”1 “noblewomen,” or “grand ball.” These words, themselves adorned with frills and each of equal weight, dazzlingly begin to narrate their own histories. There may also be a lyric poem like those that once, each month, adorned the title pages of magazines for girls.

Faintly a poppy blooms

First one and then another ...

In the soft wheat field

In a garden wafted on the breeze

The fading sun hovers on the evening horizon

The moon trembles in a dream

A piano begins to sigh

The sound of weeping in the evening

In the mist over the wheat field

In the bosom wafted on the breeze

Faintly a poppy blooms

First one and then another ...

(Kitahara Hakushū, “Faintly a Poppy Blooms”)

The word chain flutters and ripples, calling to the reader as a poetic “play of sounds,” an audible accompaniment to the visible movement of ribbons and frills. And, emerging from the center of this vision we see a figure orchestrating the never-ending flow of signs. We might expect this figure to be a dignified noblewoman or a person of power and wealth. Yet such a form is nowhere to be seen. Instead, standing in the center ground is none other than the girl – the shōjo.

In this chapter I will examine and probe the significance of the notion of hirahira, the term I use to describe the movement of objects, such as ribbons, frills, or even lyrical word chains, which flutter in the breeze as symbols of girlhood.

“Girlhood” (shōjo no toki) is often likened to the sleep of a pupa awaiting transformation into a butterfly, a time spent in a closed world. We might recall, for example, the hundred-year slumber of the Sleeping Beauty or the temporary death of Snow White.

There comes a day when the girl realizes that she herself is a shōjo, a day she also learns she can never be a boy, a shōnen. From that time it is as if she spins a small cocoon around herself wherein to slumber and dream as a pupa, consciously separating herself from the outer world. Here, she lives life to her own time, a time that can never be lost.

But, regardless of the cocoon spun in secret, the fluttering motion of ribbons and frills asserts her “girlhood.” The girl may try to avoid contact with the outside world when in her self-contained, inwardly converging state; nevertheless, her constant swaying and fluttering provokes and attracts the gaze of others. This double structure marks the advent of girlhood and gives rise to the “state of being a girl.”

The following modest essay is my testimony as someone who once experienced “girlhood.” It is also my attempt to interpret “the state of being a girl” to others who have spent time as a girl. “Girlhood” is a topic that has long been neglected and even dismissed as an object of derision. The world of the girl has, therefore, been marginalized as a “field unworthy of discussion.” This position conceals the logic of non-girls who seek to justify themselves by neglecting the girl. However, we must also acknowledge the logic of the girl herself, who protects her own time by, to some extent at least, welcoming this neglect. The history of all children's culture is woven from the subtle interplay of these two sides.

In order to shed light on this “untouchable world” I will use two different languages. When narrating my days as a girl, I will use the language of one who was “once a girl.” However, when analyzing the significance of these experiences, I will use the language of one who is “no longer a girl.” Like a toccata and fugue, may the different keys of these two language registers resonate in mutual harmony as they express the various aspects of “girlhood.”

The first movement: landscape with girl

The world of Yoshiya Nobuko

The pretty, fragrant, delicious things in life are no more. In their stead, posters with the slogan “Abstain until Victory” are now everywhere around the town. Once more today, I waved the Japanese flag and farewelled soldiers leaving for the front. Women at a street corner called me to help them sew a senninbari, the good luck belt sent to men fighting in the war. I stopped and added a stitch.

But once alone I enter a “different time.” Here in a room redolent with the imagined fragrance of hot-house freesias, my heroines, in crimson crepe-de-chine Sunday dress or pink organdie afternoon frock, accompany themselves on the piano and sing Wilhelm Arendt's “Forget-me-nots.”

The air is filled with exquisite words that float and flutter in the faint breeze before me. The Tiger Finch, Forget-Me-Nots, Pink Seashells. Even the row of titles on the shelf performs a dreamy harmony. I need hardly say that all these books are by Yoshiya Nobuko. The exotic foreign words scattered across the pages transport my mind to far off places.

I take up a book and open it. The table of contents includes: “To my dear dark-eyed one,” “Fallen life, remnant flower,” “On a day of light snow.” Of course, my fantasy heroines must have eyes as darkly limpid and shining as obsidian, while snow must always be fresh and light, never heavy or moist. These heroines are known by wonderfully distinctive names, such as Mayumi, Aiko, and Tamaki. Unfortunately, I have the very common name, Masuko.

Some adults cruelly criticize Yoshiya Nobuko's writing, claiming it is “frivolously unrealistic.” How can they say this? To me, her work is never frivolous or unrealistic. On the contrary, reading her novels lifts me up and fills me with joy. “I had planned to let you take riding lessons when you were a little older,” my mother said. These words provide a ray of hope, even though the war has made it unlikely I will learn to ride a horse. But if I could, I would have at least one thing in common with my heroines. “Besides,” I think secretly to myself, “perhaps when I turn fifteen ... ” I would so love to try on the imported petticoat Mother keeps deep in a chest of drawers. She also has a silk slip, soft and smooth against the skin, and trimmed at the hem with handmade lace. I would spray myself with her precious Houbigant perfume and lightly color my lips with Coty lipstick. How wonderful to be fifteen.

I grew up in a time of scarcity. But when I was in primary school, my mother bought me the Collected Works of Yoshiya Nobuko, concerned though she was that “This may be a little old for you.” I also somehow knew that later she would give me the few luxury items she had secretly stored away in a chest of drawers.

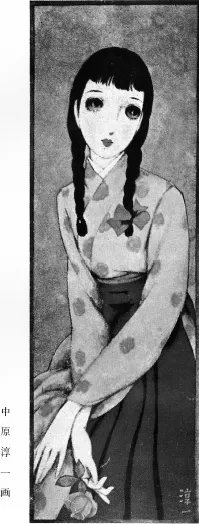

Jun'ichi’s maidens

Where does the painter Nakahara Jun'ichi find such beautiful girls? Their wide-open eyes cast no reflection, for all they see is dreams. Their tiny mouths will never eat or scream. They have long limbs and waists so slender I could encircle them with both hands.

Some of Jun'ichi’s girls have ribboned bows swaying at the end of their plaits or in the soft waves of jet black hair flowing over the billowing fullness of their gathered sleeves. Some wear indigo cotton kimonos as they stand in the breeze that somehow always wafts through Jun'ichi’s paintings, and which lifts the long sleeves of their kimonos higher than the corn growing in the background. Other girls wear skirts that dance in the breeze with the “fallen leaves of plane trees.” Ah, the fallen leaves of the plane trees.

This maiden in the white blouse with lace collar and cuffs must surely be Mayumi, while the girl in pink is certainly Yōko. Who else but the “Queen of the Classroom” would dare adorn herself with such stunning frills? And could that girl wearing hakama trousers a little short over her kimono be a star of the Takarazuka Musical Theater?2 Perhaps it is “Amatsu Otome” or “Kumono Kayoko.”

Figure 1.1 Nakahara Jun'ichi’s illustration for Yoshiya Nobuko

Source: Hana monogatari, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1995, vol.1, frontispiece.

The maidens created by Jun'ichi’s brush stand here before me in their beauty. Boys will tell you they are all alike, but each is different and has her own tale to tell. Some boys outrageously claim that only monsters have such huge eyes and tiny mouths. Others say that girls so thin must be tubercular.

It is better not to show Jun'ichi’s paintings to boys or adults. Instead, I will keep them as my secret treasures. My older cousins are lucky enough to have boxes filled with illustrations by Jun'ichi cut from old copies of Girl’s Friend. How I wish that I, too, could have such a collection.

Although it was my mother who bought the Yoshiya Nobuko collected edition for me when I was still quite young, she seems not to have heard of Nakahara Jun'ichi. Occasionally, however, she mentions the names Yumeji and Kashō, artists who apparently added color to her life as a girl.

The words of lyric poems

Now and again, the words of lyric poems come to visit me in my room. I borrowed an old copy of Girl's Friend from a cousin. The front page featured “Golden Sunflower,” a poem by Kitahara Hakushū:

Golden sunflower woebegone

Thou too art weary of the sun

Under the heat of the southern midday sky

How sad and tired thou dost look.

Pondering these lines, I, too, feel a burning sensation and the pathos of the scorching midday sun. It is not only autumn and its fallen leaves that are sad and lonely.

What a great word magician is Hakushū! The term most commonly used for sunflower is himawari. This reminds me of hima, the castor-oil plant, one of the crops the government instructed us to grow. Both plants give the feel of being overly strong and ferocious. But the poet uses the expression kogane higuruma, golden sunflower, and thus creates an altogether different impression. Higuruma means vehicle of the sun. It is a flower that perpetually rotates its face towards the sun for which it longs. How passionate this image is. And how sad.

Hakushū laments the “sorrow of a green fruit” and wonders “was that the voice of the falling leaves?” This poet fills my hours with wondrous words far removed from the real world sunflower that grows haughtily along a fence, or the green plums waiting to ripen in a corner of the garden. And his fallen leaves are nothing like the dead leaves that cover the school ground in autumn. How tiresome it is to be given ground duty and made to sweep these up. However, when surrounded by poetic words, I can secretly love the “forlorn exquisite world” to my heart's content and, “in rapture,” long for things unseen.

Yosano Akiko is another poet who transports me to a wondrous world.

Longing for the sea, I counted the distant roar of waves

As I became a girl in the home of my parents

Blooming in the boundless blue world once upon a time

with me, white chrysanthemums

“Ladies’ chamber,” “jewels”: how luxuriant her words. She repeatedly whispers the verb “to long for”: “to long for a lover,” “to long for an unknown foreign land,” “to long for the past.” And how marvelous that she has the name “Akiko.”

In the same way that Jun'ichi paints nothing but the fictional heroine, the lyric poet never depicts objects in the real world. In public, I sang “We little Japanese keep on winning” at the top of my voice. However, my inner world was strangely sealed against these realities. Once in this world, I settled peacefully into a completely separate time, a time that remained with me forever and in which there was neither war nor air raid. It was a haven in which nothing but beauty floated and danced.

Soon afterwards the evacuation began. When packing, priority was given to my parents’ books and things like the World Classics. The Yoshiya Nobuko collection was left behind. I calmly accepted this unfair treatment: somehow, it was expected. Perhaps I did so because, clad in my padded airraid hood, I had been trained as “a girl of the military nation.” Or perhaps any girl would react like this.

The second movement: a study of girls’ culture

Boys’ fiction versus girls’ fiction

Between about 1925 and 1940 there was a huge growth in the popularity of fiction for boys and girls. The former was associated with the magazine Shōnen kurabu (Boys’ Club). Its representative writers included Satō Kōroku, Yoshikawa Eiji, and Osaragi Jirō. The emergence of writing for girls centered around the Shōjo no tomo (Girls’ Friend) magazine and Yoshiya Nobuko.

Until now, conventional studies of children's literature ignored these genres, leaving them neglected and overlooked by scholars. In other words, in spite of the fact that these works were read and enthusiastically embraced by large numbers of readers, they were excluded from the study of children's literature and regarded as unworthy of that name. Researchers working in this area occupied themselves solely with the rise and fall of the Red Bird3 movement and the proletarian children's literature that replaced it, hastily constructing schematic explanations of these movements in direct relation to the social context of the time. Thus specialists drove the fiction of boys and girls to the periphery. Here it was branded with discriminatory terms such as vulgar and inartistic and, thus, buried away.

However, in conjunction with growing scholarly interest in the ideal image of the bo...