![]()

1 Introduction

The U.S. has become increasingly diverse, fueled in large part by increased immigration from Mexico and Latin America. Latinos1 are currently the largest and fastest-growing population in the U.S., accounting for over half of the nation’s growth since 2000, and by 2050 will represent more than a quarter of the country’s population (Fry 2008; Passel and Cohn 2008). This growing population is extremely diverse, as it includes many subgroups, typically identified in terms of national origin. Although persons of Mexican origin form the largest Latino population group in the U.S., sizable segments of the population also trace their ancestry to a wide range of countries and territories, including Puerto Rico, Cuba, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic (Pew Hispanic Center 2009). Furthermore, Latinos have begun to settle in “new settlement states,” including Georgia and North Carolina, in addition to traditional states like Florida and New York, ultimately increasing their geographic diversity (e.g. Marrow 2005). This is particularly noteworthy because we know that settlement patterns in ethnic enclaves serve to sustain the preeminence of nationality for many immigrant groups (Portes and Rumbaut 1996).

Group identity is most simply defined as the recognition of membership in a given group and an affinity with other group members (Garcia 2003). Although Latinos often choose to identify themselves based on ties to their home country or place of ancestral origin (e.g. de la Garza et al. 1993), they also adopt other identities that have social and political meaning. One identity most commonly studied is panethnic identity, which is largely defined as a collective, distinct, and separate identity that ties together Latinos of different Spanish-speaking populations (e.g. Padilla 1982, 1984). Much of the recent literature on Latino panethnicity explores the conditions under which this identity forms (e.g. DeSipio 1996; Itzigsohn and Dore-Cabaral 2000; Padilla 1984, 1986; Garcia 2003; Masuoka 2008) and its potential impact on political opinion and behavior (e.g. Calvo and Rosenstone 1989; de la Garza and DeSipio 1992; de la Garza et al. 1992; Stokes 2003; Jones-Correa and Leal 1996; Garcia 2006). The steady rise of Latino panethnic identification has significant implications for American politics as it suggests that there is a cohesive, unified group with distinctive and common interests and political goals. Despite the diversity within the Latino community, Latino panethnicity can be an important mobilizing political force (e.g. Baretto 2007). As result, there has been a great deal of discussion about the political relevance and political behavior of Latinos.

In The Politics of Race in Latino Communities: Walking the Color Line, I address questions about the political relevance of Latinos, focusing on identity and placing an emphasis not on national origin or panethnic identity, but racial identity. The U.S. Constitution mandates that the population be classified and counted every ten years for the purpose of representation and taxation. Since 1790, the classification directed by Article I, Section 2 has distinguished groups by race. Over the years, the classification by race has expanded and contracted, reflecting changing societal and political attitudes about race and citizenship (Nobles 2000). For example, in response to a growing preoccupation with defining Whiteness, the category “Mexican” was added to the census in 1930. With the assistance of the Mexican government, Mexican Americans lobbied against the change and the category was subsequently removed (Cortes 1980; Nobles 2000). Largely in response to demands from the Latino community, the first major attempt to categorize the Hispanic population was in the 1970 Census with the inclusion of a separate Hispanic origin question (Rumbaut 2006). Whereas the inclusion of a Mexican category in 1930 was viewed mostly as an explicit effort to stigmatize Mexican Americans, the inclusion of a Hispanic origin question was welcomed in the post–civil rights era as a source of data that could be used to protect Latino rights (Perez and Hirschman 2009: 8). The U.S. federal government defines Latinos as a panethnic group that includes persons of “Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race” (Office of Management and Budget 1997). Because Hispanic origin (ethnicity) and race are treated as distinct and separate concepts in the census, respondents who ethnically identify as Latino/Hispanic may also identify with any of the five minimum race categories determined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget’s 1997 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; and White. Furthermore, respondents are also permitted to choose more than one racial category or select a sixth category added to the 2000 and 2010 Census questionnaires—some other race. When asked to identify themselves using these categories, Latinos make distinctive choices, most choosing to self-identify as White, other race, or Black (Ennis et al. 2011; Logan 2003; Grieco and Cassidy 2001). My interest is in exploring the diversity of racial identities in the Latino community and the social realities these identities create. Therefore, the purpose of this book is to reconceptualize the study of Latino politics by focusing on the development and political consequences of Latino racial identity.

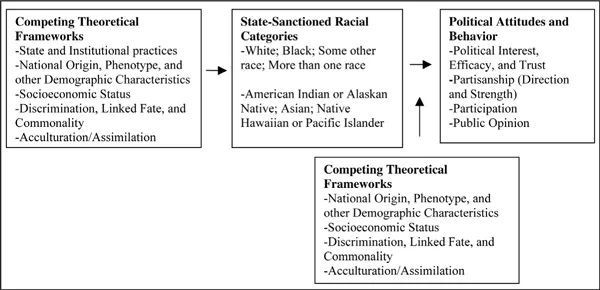

Conceptually, this book rests on several theoretical frameworks that inform our understanding of Latino racial identity formation (see Figure 1.1). Scholars have long argued that racial identities are constantly negotiated among the individual and society (Cornell and Hartmann 1998; Nagel 1995). Race is a dynamic social construct (Omi and Winant 1994), and thus the manner in which Latinos racially self-identify is not only a product of individual preferences and choice but of the social and political construction of the concept of race and racial boundaries in the U.S. One theoretical approach highlights the role of the state and institutional practices in racial formation. By counting groups of people through the census, the state determines which groups are legitimate members of the body politic and which social categories are acceptable (Kertzer and Arel 2002). A boundary-centered framework suggests that institutional actors like the state play a role in creating racial categories to legislate inclusion or exclusion (Wimmer 2008b; see also Frank et al. 2010). In the case of Latinos, the decision by the government to treat race as distinct from ethnicity creates a context where Latinos, individually and collectively, struggle over “which categories are to be used, which meanings they should imply and what consequences they should entail” (Wimmer 2007: 11). Latinos, particularly those who are foreign born, are challenged to disregard the complexity of their own national experience and submit to the logic of the dominant racial hierarchy of White and Black (e.g. Torres-Saillant 1998). Consequently, decisions made by the government have far reaching implications for demography, including how Latinos will be described and the number and type of racial options they can select. Therefore, Latinos’ racial choices are in reaction to existing categorical boundaries dictated by the state. Those choices include rejecting existing racial boundaries by refusing to respond to race questions; challenging established boundaries by self-identifying as “other”; or accepting the boundaries by choosing standard racial categories (Wimmer 2008a; for further discussion see Frank et al. 2010).

Figure 1.1 Modeling the development and political consequences of Latino racial identity.

Another framework focuses on the process of racial categorization and classification in Latin American countries to improve the understanding of Latino racial identification choices in the U.S. Approximately 40 percent of all Latinos are immigrants (Suro and Passel 2003) and bring with them an understanding of race vastly different from the one predominant in the U.S. Upon arriving, Latinos are immersed in a culture where the dominant racial paradigm is based on Black and White identity. In contrast, many Latin American and Caribbean countries have a ternary model of race relations that acknowledges intermediary populations of multiracial individuals (e.g. Daniel 1999). Coming from backgrounds where racial boundaries are loosely drawn and racial mixing is common, Latinos often see themselves deriving from more than one race (Rodriguez 1992, 2000), in part because race is largely defined by national origin, nationality, ethnicity, culture, skin color, or a combination of these (e.g. Kissam et al. 1993; Bates et al. 1994; Rodriguez and Cordero-Guzman 1992). Yet migrating to the U.S. is assumed to alter Latinos’ racial identities (Itzigsohn et al. 2005), as they are often presumed by others to be either Black or White. Encountering a disparate racial classification system, Latino immigrants may change their racial identifications as they adapt to the U.S. racial classification system (see Golash-Boza and Darity 2008: 904). Latinos born in the U.S. may also re-categorize their racial identity as they navigate between the system of racial classification of their immigrant relatives and that of mainstream U.S. society (e.g. Marrow 2003; Bonilla-Silva 2003). This is clearly the case for many second- and third-generation Latinos, who are more familiar than their parents with the U.S. race classifications but are likely to be influenced by that of their parents and grandparents.

Theories of assimilation and acculturation have also been used to inform our understanding of Latino racial construction. Classic assimilation theory suggests that as Latino immigrants and their descendants move into the mainstream, they will eventually share a common American culture and achieve access to social, economic, and political institutions. As they are incorporated politically and socially, Latinos’ ethnic attachment should be less relevant and less politicized. Critics of this conceptual framework often argue that some groups may not assimilate because they face severe discrimination and therefore have limited socioeconomic and political mobility. The theory of segmented assimilation advanced by Portes and Zhou (1993) posits three possible paths particularly for immigrants of color: assimilation into the White mainstream, identification with the Black underclass, or a new path in which immigrants deliberately retain the culture and values of their immigrant community. The degree to which Latinos are incorporated into American society should also influence Latino racial identity formation, so whereas social mobility into the mainstream may encourage some Latinos to racially self-identify as White, everyday social interactions that include experiences of discrimination based on perceived group membership may encourage some Latinos to choose other racial identities (Golash-Boza and Darity 2008; Landale and Oropesa 2002; see also Tienda and Mitchell 2006).

That life experiences and social interactions influence the way individuals view themselves racially suggests that shared experiences lay a foundation for group identification (e.g. Omi and Winant 1994; Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Rodriguez 2000; Waters 1999). A social identity framework focuses on the creation of group boundaries and holds that individuals align themselves and identify with members of social groups with which they feel commonalities (Tajfel and Turner 1986; Tajfel 1981). Similarly, believing that one’s life chances are connected to the fate of a particular racial group and that the social and political problems experienced by that group are specifically associated with their race may also encourage some Latinos to adopt a particular racial identity (e.g. Dawson 1994). Adapting social identity theory and Dawson’s notion of the “Black utility heuristic” to the Latino experience, it is likely that perceived commonality and a feeling of shared or linked fate with non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks and with Latinos from different national origin groups are also consequential to the understanding of Latino racial choices.

In summary, the structuring of Latino racial identity is a complex interaction between policies of the state and institutional practices, primordial ties, individual characteristics, and social interactions. Thus, the theoretical approach used in this book to explore the foundations of Latino racial identity includes socio-demographic factors (including national origin, phenotype, and socioeconomic status), individual perceptions of discrimination, linked fate and commonality with other racial groups, and measures of acculturation/assimilation. However, understanding what factors influence the development of Latino racial identity is only part of the story. Exploring the way in which Latinos construct their racial identity raises the question of whether racial group attachment among Latinos influences the formation of individual political attitudes, thereby creating substantial subgroup variations within the Latino population. Simply put, I contend that racial identity influences Latino politics, translating into politically meaningful behavior and attitudes at the individual level. Thus, we should expect to find variation in Latino political behavior. To be clear, extant research has found that many of the factors derived from the conceptual frameworks briefly outlined above explain this variation. Here I argue that variation in Latino politics can also be attributed, at least in part, to racial identity. Why might race be a predictor of Latino attitudes and behavior? Arguably, a number of social identities exist but are irrelevant to politics. What makes racial identity different? Why for Latinos might there be a connection between their racial identity and politics?

Social identity theory stresses that individuals’ identification with overarching societal structures, such as groups and organizations, guide internal structures and processes. Social group identity is shared with a group of others who have (or are believed to have) some characteristics in common. Individuals align themselves with members of social groups with whom they feel commonalities, and over time develop part of their identity around such membership. Thus, group identity embodies strong social attachments and collective political evaluations and has come to be understood as a valuable political resource, playing a significant role in participation and attitude formation (Gurin et al. 1980). When an individual identifies solely with a particular group, there is a “self-awareness of one’s objective membership in the group, as well as a psychological sense of attachment to the group” (Conover 1984: 761). At the most basic level, individuals can determine whether they are part of an in-group or out-group in reference to a target individual or group. It is this determination of group membership (and the status that comes with being part of that group) that provides reference points for political choices and behavior.

Race has long been used to classify groups of people in the U.S., creating a dividing “color line” (Omi and Winant 1994; Nagel 1994). Racial identities assigned to subordinate groups have created a lived context in which an individual’s racial identity structures that individual’s life chances. Thus, because race plays a significant role in determining the life chances and social position of groups, it is possible that racial self-identification within the Latino community will influence individual political attitudes and behavior. Racial identities become salient and politically relevant when individuals define themselves as members of a group (Tajfel and Turner 1986) and realize that their life chances are connected to the fate of a particular racial group (Dawson 1994). Much of the early research on the political effects of group identity focused exclusively on African Americans and found that racial group attachment influences political attitudes and behavior. Despite economic and social cleavages in the African American community, African American political attitudes and behavior have been largely homogeneous because individual self-interest stems from group interests (Bobo et al. 2001; Dawson 1994; Kinder and Sanders 1996), creating a sense of commonality and political unity. Ethnic group identity functions in a similar fashion, shaping Latino attitudes and behavior (e.g. de la Garza et al. 1991; Calvo and Rosenstone 1989; de la Garza and DeSipio 1992).

Although ethnicity (particularly national origin) may be a primary (and the most preferred) identification for Latinos, the imposition of racial categories by the state signals the potential importance and relevance of race (and racial identities). Mainstream society typically classifies and treats most Latinos as non-White (Rodriguez 2000). Furthermore, numerous reports suggest that racial identity has real consequences for Latino life. Using 1970 and 1980 Census data, Massey and Denton (1992) find that White Latinos experience the greatest degree of spatial assimilation, living in closest proximity with non-Hispanic Whites, whereas Black Latinos remain highly segregated from non-Hispanic Whites. White and Black Latinos also live segregated from each other. The 2000 Census data shows that White Latinos have the lowest rates of poverty and higher incomes, followed by Latinos who racially self-identify as some other race, and Black Latinos. Despite having higher levels of education than other Latino racial groups, Black Latinos have the lowest incomes and highest rates of poverty (Logan 2003). If one takes a sociological view of the world, where life experiences and social interaction shape beliefs and actions, the reality that race is a fissure in Latino life increases the possibility that race could be a key component of Latino identity and is therefore politically significant. The social implications attached to a racial identity influence the individual’s worldview, which then frames that individual’s political perceptions. Because individuals perceive that their life chances are shaped by race, they may be more likely to rely on that identity to make political judgments (e.g. Dawson 1994). In this case, the socioeconomic advantage of White Latinos and socioeconomic vulnerability of non-White Latinos seems likely to have some degree of influence on their politics.

Connecting asserted racial identities to their effect on the political process has proven to be an overlooked yet notable aspect of Latino politics. The few studies that explore how racial identities affect Latino political choices all suggest that race has important implications for political behavior and policy. For example, Black Latinos are more supportive of government-sponsored health care and less supportive of the death penalty than are White Latinos. They also express a greater sense of commonality with African Americans, whereas White Latinos feel closer to non-Hispanic Whites (Nicholson et al. 2005). Race is also a significant predictor of Latino vote choice and political attitudes. When given the choice between a Latino candidate and a non-Latino candidate, Latinos who racially identify as Latino are more likely to choose the Latino candidate, whereas White Latinos and those who identify as other race are le...