1.1 Introduction

Since Grossman published his groundbreaking piece on the concept of health capital in 1972 economists have applied the concept both theoretically and empirically with much success (Bercowitz et al., 1983; Karatzas, 1992, Picone et al. 1998). However, most authors have not made a clear distinction between “functional health” and health stock. The original paper by Grossman (1972) had assumed – largely for expediency – that “health services,” i.e., the benefits that arise from the health stock in each period and another term for “functional health,” is directly proportional to the stock of health. Henceforth, however, authors typically assume that a larger stock of health must imply a larger flow of health services. For example, Picone et al. (1998), uses health stock rather than functional health as an argument in the utility function in each period, which would not make sense unless in each period the service flow is directly proportional to the stock. Folland et al. (2010) are more explicit about the distinction between health stock and functional health, but are certainly mistaken in the statement that: “The greater one’s stock of health [is], the greater the number of healthy days, up to a natural maximum of 365 days [will be]” (p. 141). The assumption that flows are directly related to stocks is often correct, but as demonstrated below is not always true. The concept of functional health is not unfamiliar among researchers in the health sciences (Hornbrook and Goodman, 1996; Kington and Smith, 1997), but is seldom explicitly discussed in the economics literature. This chapter will fill this gap.

The health of a person can be looked as a condition that can improve or deteriorate as the individual recovers from or falls into sickness. This “condition,” however, is actually a stream of functioning capability that we can refer to as functional health. In contrast to functional health, the health stock of a person can change without the individual’s noticing it. The health stock can be looked at as a store of such capability that can serve the person into the future. This store may change without our noticing. Perhaps a tumor is developing in its early stage. Perhaps some blood vessels are blocking. Perhaps the individual is infected with HIV or a parasite. In other words, the individual can function at a normal level, i.e., “functional health” may still be at a high level, and yet his stock of health may be quietly falling.

Some drugs are known to increase functional health momentarily, but at the expense of the stock of health. Under influence from the drug, an individual may perform better, concentrate better and enjoy a feeling of better well-being. Yet he may be drawing down his stock of health. Functional health has many aspects: the general feeling of well-being, the faculties of sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, speech and mobility. Since severe pain distracts and disables, a pain killer will improve functional health, but a strong pain killer, such as morphine, can damage the stock of health. Similarly steroids can quickly improve functional health, but can also produce side effects that may undermine health over the long term.

The distinction between health stock and functional health is useful in discussions relating to health policy because there is an obvious need to balance measures devoted to improving or maintaining the health stock and measures devoted to improving functional health. The choice over these two aspects of health is related to the discount rate (time to translate future benefits to the present). If the rate of discount is higher, implying stronger time preference for the present, functional health will be given greater weight relative to the health stock. If the rate of discount is lower, on the other hand, replenishing or protecting the health stock will be given greater weight. A high rate of discount is one of the reasons why some individuals choose to take drugs that may enhance their functional health in the short term but may hurt the stock of health over the longer term.

Proposition 1.1: Distinction between functional health and health stock.

Functional health is a flow, and flows have a time dimension. Functional health is a service provided by the health stock. In general, a larger health stock can be expected to provide more years of functional health. The reverse, however, is not true. Very high functional health in a particular year does not necessarily mean that the stock of health is high. One could feel fine and could function extremely well without realizing that one’s health is being eroded by some unknown illness.

In general, given the state of technology, the health stock will inevitably depreciate over time. Appropriate healthcare, however, can slow down the speed of this depreciation. But this must involve various kinds of sacrifice. There is in principle a different “optimal rate of depreciation of the health stock” for different members of society. The optimal rate of depreciation is defined as occurring when the marginal cost involved in slowing depreciation is equal to the marginal benefit. This marginal cost may be an out-of-pocket expenditure, the cost of a drug, for example. It may also be the opportunity cost of a change in lifestyle, which may be quite personal and subjective. Health policy should allow each person to achieve his optimal level of depreciation of the health stock by making an intelligent, informed choice and by affording him the means of making such choices. These aspects of optimization are extremely complex and they involve many decision makers in both the private and the public sectors weighing the benefits against the costs of healthcare, and weighing the benefits and costs of alternative lifestyles.

Proposition 1.2 Optimal health stock depreciation

The optimal rate of health stock depreciation is achieved by adjusting behavior, typically aspects of lifestyle, so that the marginal benefit of slowing depreciation in terms of the value of a longer life over the longer term, is equal to the marginal cost of that preventive behavior, either in terms of the sacrifice in enjoyment of an activity or in terms of a direct outlay.

1.2 Functional health as a “good”

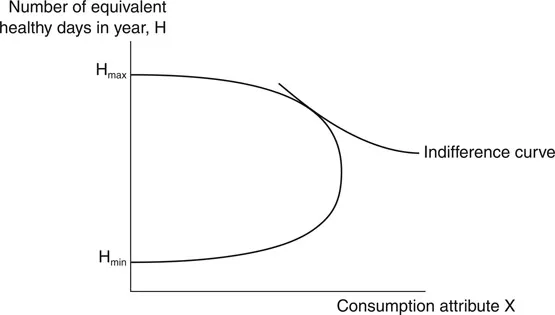

We can measure functional health in a year as the number of “equivalent healthy days” (EHDs) in that year.1 An EHD is a day of “normal functional health.” A day with a loss of functional health may be discounted and treated as a fraction of a day of normal health. Because functional health contributes to the quality of life, which may involve many different dimensions, the concept of functional health is not exactly the same as the related concept of “quality adjusted life-year (QALY)” (Broome, 1993). In the rest of this book we will focus on EHD instead of QALY. EHD is considered an input along with market goods and services in consumption activities (also called “household production”2) that yield the “consumption attributes” X which affect utility. We can draw the “(functional) health production possibility frontier” (HPP) applicable to one individual as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Functional health production possibility frontier.

Here Hminis the number of EHDs that would occur even when there is no healthcare input allocated for the purpose of increasing health. Starting from this level, suppose some medical input is now used to increase functional health. Because functional health is needed to enjoy life it is possible to increase the enjoyment of consumption attribute X while at the same time enhancing H. Beyond a point, however, it is possible to increase functional health only at the expense of X. Finally, there is a limit to which medical input can be used to enhance the number of EHDs and this is represented as Hmax. Hmin, Hmax, and the curvature of the production possibility frontier depend on the stock of health of the individual at the time as well as the state of medical knowledge.

We can now superimpose the indifference map onto the diagram. We can then easily see that optimality in the sense of utility maximization subject to the (functional) health possibility frontier generally implies that functional health will not normally be maximized. The simple reason is that beyond a certain point improving functional health carries a price in terms of the enjoyment of other goods and services. While it is generally not in the interest of utility maximization to maximize functional health in a year, it will be in the interest of long term utility maximization to conserve health, i.e., to slow down depreciation of the health stock. Again, however, there is an optimal rate of health stock depreciation. Reducing the rate of depreciation brings a return in terms of greater functional health in the future, but it also carries a cost in terms of loss of some consumption opportunities.

In general, as the individual’s stock of health depreciates over the course of his life we expect that the HPP will drift downwards. In the short term, it is also possible for the HPP to shift down with the working of some random factors such as the outbreak of some epidemics.

1.3 Prevention versus treatment

The stock of health generally depreciates over the life cycle of a person. Depreciation may be slowed down both by prevention and by treatment. Prevention reduces the chances of health threatening events, so that episodes of rapid depreciation in the health stock will be minimized. Treatment reduces the impact of health threatening events that have already taken place. Treatment may help restore functional health, and may also restore the health stock or save it from dangerous depletion.

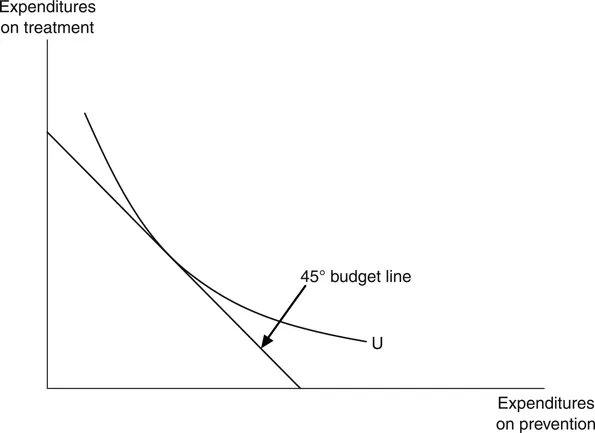

It is common to say that prevention is better than cure. This is often true in the sense that once a health threatening event has taken place, often irreparable damage to the health stock may be unavoidable, but the health threatening event may actually be avoidable. However, from the policy point of view, optimal resource allocation between prevention and treatment will occur when at the margin the benefits of prevention and treatment are the same. This is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Optimal balance between cure and prevention.

Proposition 1.3 Optimal prevention and treatment

When allocation is optimal, the marginal benefit of a dollar spent on prevention should be equal to the marginal benefit of a dollar spent on treatment.