![]()

1 A comparative study of social capital

The essential building blocks of the social world are relations among human beings. Like it or not, a significant part of one’s social life is composed of ties with others who are either immediately or indirectly related. Figuratively speaking, humans are not isolated islands floating around an infinite ocean (Flap 2002); rather, people usually form specific relations with others in structurally arranged and, to some significant extent, confined areas of social life. This means that there are structural forces that prearrange the general settings of social relationships even before actors appear on the scene and choose their social contacts out of the seemingly countless people around them. In other words, the choices of social relations are far from a random selection.

For example, it is not likely that a five-year-old boy in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates could befriend another five-year-old boy in Seattle, Washington in the United States. If this geographic barrier sounds too obvious, it may be that a temporary Mexican migrant construction worker in the United States cannot make regular contact with a local white-collar manager in the IT industry, even when geographic distance is removed. Further, it is well known that even in a single society, racial/ethnic groups, if any, have a strong tendency to maintain predominantly homogeneous in-group ties; as a result, interracial or interethnic ties are significantly fewer. In addition, ethnic differentiation even within a race can hardly be ignored, as in the tragic “ethnic cleansing” of Tutsi by Hutu in Rwanda in the mid-1990s, even though the deadly antagonism between these two ethnic groups was much affected by the Rwandan postcolonial legacy. Even when visible cues of collective differentiation do not exist in racially and ethnically homogeneous societies, dialects may instead work as verbal signals of regional origin, and minute linguistic differences among regions may form invisible but effectively exclusive structural boundaries among social groups, as we see from the long-standing conflict between the Young-nam and Ho-nam regions in South Korea. Religion should not be omitted from the list of possible structural barriers of social relations, as the history and current affairs of Europe, Africa, and Asia have shown; it is perceived to be the core pillar in the clash of civilizations in the post-Cold War era (Huntington 1996). Of course, the existence of structural barriers does not mean that all social relations are predetermined and actors accept them unconditionally. Nonetheless, one cannot deny that the pattern of social relations is strongly associated with social structure. Therefore it is necessary to understand macrostructural or institutional constraints that affect how the pattern of social relations is formulated. These constraints can be composed of a variety of factors such as race and/or ethnicity, gender, or types of political economy in accordance with the set of unique contextual factors of a given society.

Structuring of social relations

According to Breiger (2004), who tracked down the metaphoric use of networks to several key figures in sociology, Marx stated, “Society is not merely an aggregate of individuals; it is the sum of the relations in which these individuals stand to one another” (Marx [1857] 1956: 96, cited in Breiger 2004: 505). Thus interest in social relations is as old as the history of sociological enterprise itself. In particular, from its incipient period sociological enterprise has had much stake in the relationship and interaction between social relations and macrostructural factors (Durkheim [1895] 1964; Simmel [1922] 1955). For instance, Durkheim proposed the idea that individual identity and behavior are affected by the social location of an actor, and social networks among actors are conduits of new economic rules formed among occupational categories in modern and industrialized society (Durkheim [1893] 1984; Dobbin 2004). Thus individuals are not individuals per se in sociological research; they are enclosed within and interacting with the social structure in which they are embedded. This is the basis of the Durkheimian argument that self-interest-seeking behavior of each actor based on egoism does not guarantee social integration but could instead be deleterious to both individuals and community (Tiryakian 2008). In an extreme case of strong embeddedness, social structure and societal force may sometimes generate indirect cause of altruistic suicides committed by those who believe they should do so for the benefit of moral commitment and social integration (Durkheim [1897] 1951). Again, it is notable that social networks exist between a macrosocial structure and individual actors, and it is through networks composed of people as their nodes that specific behavioral patterns in accordance with the structural arrangement are shared, interpreted, enforced in varying degrees, reorganized, or sometimes refuted.

Thus, over the long run, different social structures give rise to their own brands of social networks – largely affected by the distinct history and culture of each society. For instance, the social networks coined by the medieval Catholic Church that condemned wealth and exalted poverty were different from those introduced by Protestant ethics in the industrialization era in which accumulation of wealth was taken as a sign of God’s elects (Weber [1905] 1998; Freund 1968). Likewise, the Chinese dynasties under Confucian ideology organized a unique set of rules and regulations, including tacit knowledge regarding how to relate to each other by considering age, gender, or social positions, that differ to a significant extent from the principles of social relations in socialist China (Tu 1991, 1993). Further, to mention a specific dimension of demographic features, social networks of the American people in terms of their racial proportion differ before and after slavery and racial segregation, even though racial homogeneity is still a dominant tendency for both whites and nonwhites (Franklin and Moss 1994; Moody 2001).

Social capital and institutions

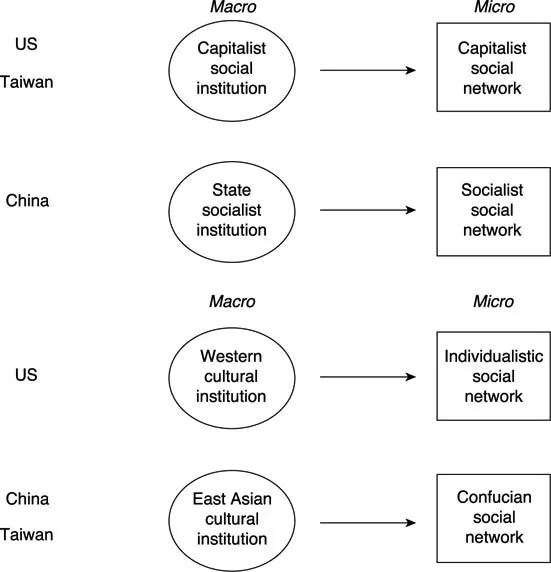

In particular, this monograph tests whether political, economic, and cultural differences between capitalist and socialist systems and between Western and Confucian cultures yield different types of individual social networks and usages (Hall and Soskice 2001).

In other words, the intrinsic principles of network composition and utilization can be dissimilar in different political economic and cultural institutions. The specific macrostructural contexts in this book take three different societal entities, China, Taiwan, and the United States. The fundamental argument is that the institutional constraints of the political economy and culture affect the composition and utilization of social capital, or social resources, in the three countries.

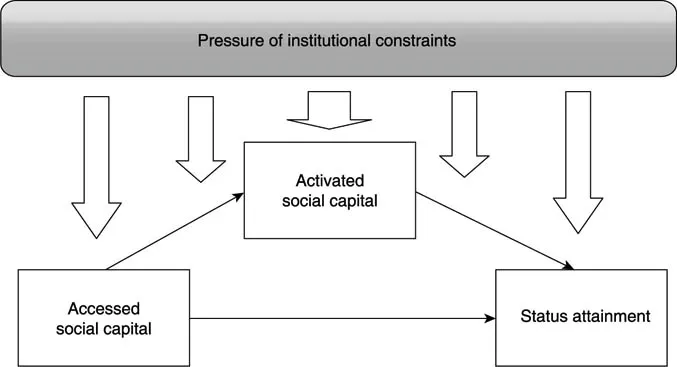

To delimit the scope of the study, in this book “social capital,” defined as “the resources embedded in social networks accessed and utilized by actors” (Lin 2001: 25), is the main variable of interest accounted for by the effects of the two macroinstitutional arrangements – political economy and culture. As implied by the definition, social capital lies in social networks at the individual level, and its volume is determined by how resourceful each node (i.e., a friend or a work colleague) of a social network is. Social capital has two dimensions: one is access (or accessibility) to the nodes and their embedded resources; and the other is activation (or mobilization) of the resources when certain instrumental or emotional needs must be fulfilled. Access is the necessary condition for activation, but it is not a sufficient condition because access may not guarantee activation all the time, and we know that in reality some ties exist that are not utilizable although they are resourceful. It is undeniable, though, that there is a strong correlation between access and activation; in other words, those who have better access to social capital are more likely to activate pertinent social resources when needed. In sum, the access dimension is related to the whole volume of social capital, while the activation dimension is associated with the efficacy of social capital by which an instrumental or expressive goal can be achieved.

Regarding the comparative study of social capital in varied social contexts, I propose that to a large extent the access dimension is formed by the effects of macroinstitutions in each given country because institutions provide different chances of creating social ties between individuals, organizations, and social groups. How are institutions related to networks in the first place? As Nee and Ingram (1998) point out, institutions exert their powers over social networks. In other words, institutions provide general principles of social relations. This is shown vividly in their definition of an institution: “An institution is a web of interrelated norms – formal and informal – governing social relationships. It is by structuring social interactions that institutions produce group performance, in such primary groups as families and work units as well as in social units as large as organizations and even entire economies [emphasis in the original]” (Nee and Ingram 1998: 19). Nee and Ingram also note that it is like seeking a missing link between network embeddedness and new institutionalism perspectives so that an integrative and balanced theoretical view of “a choice-within-institutional-constraints approach” can be generated. The present study presents an empirical trial to seek such a missing link by testing the interaction between social capital and institutional constraints.

Accessed and activated social capital

Institutions stipulate by formal and informal norms what kind of social relations are duly accessible and which are not. This structuring of social interactions at the individual level adds up to a generalized pattern of network composition at the national level, which can be compared to those from other countries.

As depicted in Figure 1.1, the key interest of the present study lies in the differential effects of macroinstitutional arrangements such as capitalist vs. socialist political economy and Western vs. Confucian cultures. Specifically, I propose that the advanced capitalist United States, state socialist China, and developmental Taiwan have formed unique sets of accessed social capital due to the institutional differences. I propose that differences, if any, in accessed social capital across the three countries can be explained at least in part by the political economic institutions (capitalist vs. state socialist) and/or cultural institutions (Western vs. Confucian) among them. My first aim is to identify variances in the compositions of accessed social capital among the countries. Above all, a uniform set of measures of accessed social capital is essential for the purpose of comparative study among different countries. A consistent comparison of the United States, China, and Taiwan in terms of their access dimensions of social capital is plausible with the help of identical measures of social capital based on the network alters’ positions in the occupational hierarchies in the three societies. I conduct the comparative study of social capital among the three case societies employing the position generator method (Lin 2001; Lin and Dumin 1986; Lin, Fu, and Hsung 2001). This approach makes it possible to launch a systematic comparative study on social capital in the labor markets of different countries.

Once the possible institutional effects on the formation of social capital are identified, the second goal of the present study is to check the effect of activation and utilization of social contacts in the status attainment process. The efficacy of activating social resources to produce beneficial returns in the labor market has been supported empirically in the literature (Lin, Dayton, and Greenwald 1978; Lin, Ensel, and Vaughn 1981; Marsden and Hurlbert 1988; Smith 2005; Wegener 1991). In line with the present study, De Graaf and Flap (1988) conducted a comparative study on the activation of social capital in the labor markets of several Western countries. They found that Americans were more likely to use social contacts than Germans or Dutch, though the data they used were neither nationally representative nor from the same survey module. Likewise, the main thrust related to the issue of activated social capital in the present study is to (1) check if the patterns in activating social resources vary in the three countries, (2) identify which people are more prone to using social contacts in the job search, and (3) test if the use of social contacts is positively related to better returns in the three labor markets and which people get the strongest effect of social resources. The analysis of whether and to what extent social resources affect social mobility may shed light on the possible variation in the role of social resources in the labor markets of the three countries.

Figure 1.1 Institutional constraints and types of social networks

Specifically, in each society I analyze two types of variations: demographic variation in the access and utility of social resources; and the relationship between tie strength and social resources. By utilizing sociodemographic categories such as gender and race, the intrasociety variation of social capital across different social groups is investigated. Females and racial minorities are expected to have less access to and activation of social capital compared with males and the racial majority. The analysis of race provides a chance to delve into the unequal distribution of social resources between whites and nonwhites, which is found only in the United States. Gender analysis generates much information on inter-and intrasocietal comparisons of accessed and activated social capital since almost every society suffers from gender inequality.

I then check whether Granovetter’s strength-of-weak-ties proposition holds in different institutional milieus related to the activation of social contacts. Granovetter states that “the strength of a tie is a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie” (1973: 1361). He then shows that work contacts (weak ties) of male professional, technical, and managerial workers are more likely to provide matches with better jobs in the job market than family-social ties (strong ties) ([1974] 1995: 45). However, the strength-of-weak-ties proposition has produced inconsistent results in empirical studies (Approval: Granovetter 1974; Lin, Dayton, and Greenwald 1978; Lin, Ensel, and Vaughn 1981 vs. Denial: Bian 1997; Bridges and Villemez 1986; Marsden and Hurlburt 1988). It is notable that Bian found that strong ties were essential bridges between job seekers and their helpers in administrative positions of job allocation in state socialist China. This case study hints at the strong possibility that patterns of tie utilization differ between capitalist and socialist countries. Furthermore, since the study tests the primacy of family ties in China, it suggests cultural differences between East Asian societies and their Western counterparts, thereby implying a possible reason for the inconsistent results of the strength-of-weak-ties proposition. In the literature role relations (families, neighbors, friends, or work contacts) of respondents have been inconsistently used to indicate strong or weak tie strength. For instance, some researchers include the role category of “friends” in strong ties (e.g., Völker and Flap 1999), whereas others include it with weak ties (e.g., Lin and Dumin 1986). Even though the strength of tie may form a continuum, the way it is measured depends on the dichotomous concept of strong vs. weak ties based on the presence or absence of ties of a specific role relation.

In order to avoid this perplexing problem of gauging the relational distance between a person and his/her contact, I introduce three structural layers of social relations: binding (family-oriented ties), bonding (daily contacts), and belonging (participation in formal organizations) (Lin, Ye, and Ensel 1999; Son, Lin, and George 2008). I propose that the structural layers of social relations function as the seedbeds of social resources. According to this schema, social relations are categorized into three hierarchical structures in which (1) binding (family-oriented ties) takes the innermost layer where human relations are initially formed; (2) belonging (participation in formal organizations) generates the outermost layer where secondary associational motivations such as political, social, economic, or religious causes, apart from primary social relations, relate social actors to one another through organizational fields; and (3) bonding (daily contacts) makes up the middle space between the informal binding layer and the formal belonging layer. In some sense, the binding layer works as a proxy for strong ties, while the belonging layer serves as a proxy for weak ties. That said, I suspect that the binding layer will be the main source of social resources in East Asian societies due to the Confucian social order of family orientation, whereas the belonging layer will produce the most social resources in the United States because it has been a country of associations from its incipient period of nation building (Tocqueville [1840] 2003). The bonding layer in between the innermost and outermost layers is conceptualized as a buffer zone in which a person interacts with network alters regardless of role relations. Logically, this layer may thus include diverse social contacts of family members, work colleagues, or comembers of a voluntary association. Nevertheless, the basic assumption is that the richer the bonding layer the better returns one may expect in labor market outcomes because the layer is an indicator of accessed social capital capacity.

As explained, it is assumed that retaining greater accessed social capital will provide a higher chance of activating it, which in turn may bring forth instrumental or expressive outcomes that were otherwise not obtainable. From the procedural perspective, the bipartite dimensions of social capital produce a dynamic process wherein the access and activation of social resources develop concurrently in multifaceted informal and formal domains of family, school, religion, voluntary associations, or the labor market, as a result of which its holders may experience higher likelihood of achieving their goals. If such individual outcomes are aggregated at the national level it is then expected that societies rich in accessed social capital will see greater returns from activated social capital on average than those that are poor in accessed social capital. Without accessed social capital or social capital capacity one is less likely to activate social capital; thus accessed social capital precedes activated social capital. In general, it is expected that the amount of accessed social capital is related to the higher chance of its being activated. However, actors with the same amount of accessed social capital do not always achieve the same outcomes; it depends on how skillfully one deploys and activates social capital for a purposive action. Likewise, activation of social capital by actors is proposed to produce a variation in outcomes in the labor market. Strategic use of the right kind of contacts can help increase the success rate of purposive actions. Thus in terms of the theoretical framework I emphasize the constraints of social institutions on the formation of accessed social capital; however, even under such constraints and the resultant limited degree of freedom, actors react to the constraints and exert their power of agency by activating social capital so that social mobility, however restricted, finds its portion in the structure, as depicted in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Moderation of the effect of social capital by institutional constraints

Therefore, activated social capital performs two major roles. First, it becomes an indicator of the power of agency. If we suppose an extreme case where activated social capital does not carry any significant effect on status attainment, we conclude that institutions nullify the choice of agency. I propose that even when institutional constraints are rigid, activated social capital still has a share in explaining the variance of status attainment. Second, the comparison of activated social capital among societies thus shows which society has stronger agency. The effects of activated social capital may vary across societies. I propose that ...