![]()

Part I

Introductory context

![]()

1 | Medical and health tourism |

| The development and implications of medical mobility |

| C. Michael Hall |

Introduction

Medical and health tourism is one of the fastest growing areas of academic research interest this century in both tourism and health and medical studies (De Arellano 2007; Reed 2008; Leahy 2008; Whittaker 2008; Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) 2009; Balaban and Marano 2010; Crooks et al. 2010; Hopkins et al. 2010; Kangas 2010; Karuppan and Karuppan 2010; Morgan 2010; Underwood and Makadon 2010; Reisman 2010; Connell 2011; Hall 2011a). The emergence of the subject is arguably a reflection of its reported economic significance, for example, Evans (2008) reported that the estimated value of the international medical tourism market was about US$ 60 billion in 2006 and projected it to reach US$ 100 billion by 2012; as well as a growing recognition of the consequences of increased human mobility, including the rapid spread of pandemics (Hall 2005; Hall and James 2011). Indeed, a significant dimension of medical tourism is the extent to which it serves as an example of the way in which globalisation is more than an abstract idea but it is something that has real effects on people and places (Woodward et al. 2002).

However, travel for health and medical reasons is nothing new and has long been recognised as a driver of visitors to destinations such as thermal springs and coastal locations as well as other areas with favourable climates (Walton 1983, 2005; Becheri 1989; Lanquar 1989; Hembry 1990; Mesplier-Pinet 1990; Niv 1989; Hall 1992, 2003; Towner 1996; Chambers 1999). In the nineteenth century, wealthy tuberculosis sufferers in northern Europe, including authors such as D.H. Lawrence and Robert Louis Stevenson, travelled to and lived in the Mediterranean, south-west United States or even in the South Pacific on advices as to the health-giving benefits of the climate in order to improve their health (Hall 2003), arguably predating modern-day lifestyle retirement and second home migration to some of the same locations for similar reasons of extending quality of life.

Historical dimensions and developments

The taking of waters at mineral spas and hot springs has occurred since Roman times and the ‘taking to the waters’ of the elites of seventeenth century Europe provided one of the foundations for the modern pleasure resort concept (Lowenthal 1962; Mackaman 1993; Towner 1996). In the United Kingdom, the development of seaside resorts, such as Blackpool or Margate, had its genesis in the belief of the British elite in the curative powers of sea air (the ‘ozone’ as it was described) and bathing in sea waters, though not initially directly in the sea itself. In the mid-nineteenth century the combination of improved transport accessibility to leisure because of the growth of the railways and economic accessibility because of rapidly increasing per capita incomes for the new middle classes led to the massification of what was previously available only to the wealthy. However, the middle and, later, working class access to the seaside resorts was built upon not only the desire for the health benefits of recreation away from urban industrial centres but also continued belief in the curative value of the seaside (Pimlott 1947; Walvin 1978; Walton 1983, 2005; Towner 1996; Hall 2003; Hall and Page 2006).

In mainland Europe, many cities and towns have grown up around mineral springs and health spas include Baden, Lausanne, St. Moritz, and Interlaken in Switzerland; Baden-Baden and Wiesbaden in Germany; Vienna, Austria and Budapest, Hungary (Goodrich and Goodrich 1987; Towner 1996). There is also a long history of people using spas and mineral water since ancient times to cure such ailments as rheumatism, skin infections and poor digestion (Becheri 1989; Carone 1989; Erfurt-Cooper and Cooper 2009; Smith and Puczkó 2009). Some spring waters are exported internationally, including Apolinaris from Germany, Hunyadi-Janos from Hungary and Vichy from France. Indeed, the sale of bottled water, including the export of brands such as Perrier from France, is perhaps testimony to the continued belief in the healthy characteristics of mineral water, although research suggests that there is considerable variability in the mineral content of commercial bottled water with subsequent implications for their actual health effects (Garzon and Eisenberg 1998).

In the United States and Canada, mineral springs even provided opportunities for the development of spa tourism around which were created some of the first national parks (Runte 1979; Buchholtz 1983; Frost and Hall 2009). Indeed, Hall (2003) even suggests that the growth of public interest in adventure, health and wellness in tourism and leisure in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries parallels the attention given to the physical, moral and spiritual ‘damage’ of urban living at the turn of the nineteenth century in North America, Europe and Australia, and the resultant growth in national parks, sport and physical education as formal recreational activities and spaces (Altmeyer 1976; Nash 1982; Hall 1985). In the contemporary travel setting, the escape or ‘push’ from mundane or alienating urban environment and lifestyles has been long recognised as a major motivating force in tourism (Hall 2005). In addition, the desire for a perceived healthy lifestyle is a major component of leisure behaviour and products related to spas and wellness that have become increasingly important in tourism since the early 1990s (Erfurt-Cooper and Cooper 2009; Smith and Puczkó 2009). Finally, one can note the role of fashion and the significance of body image as major influence on individual motivations not only to attend beauty clinics and spas but, in more extreme expressions of concern over body image, to engage in cosmetic surgery as part of so-called ‘surgery tourism’ (Grossbart and Sarwer 2003; Birch et al. 2010; Edmonds 2011; Jeevan et al. 2011).

Recent rapid growth in the field

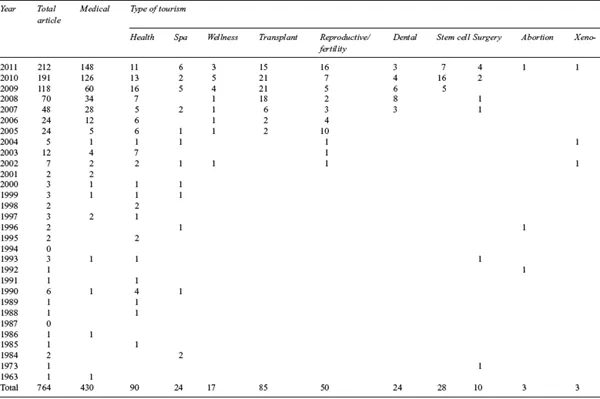

The relationship between tourism and health and medicine is therefore clearly not new. However, even though it is hard to quantify exactly, it is clear that there has been a massive shift in the amount of medical-related mobility. Allied with the growth in the numbers of people travelling for medical and health reasons has been an increasing embrace by governments of market solutions to the problems of providing medical and health services to populations that are not only increasing but are also aging. This has also meant that since the late 1990s there has been a significant qualitative and quantitative change in how health and medical tourism is reported and understood (Hall 2011a; Mainil et al. 2011). One way of illustrating this is shown in Table 1.1 which details the number of articles on medical and health tourism and cognate terms recorded in the Scopus database. Even disregarding issues of definition, which is discussed in greater detail below, it is apparent that there has been a massive shift of awareness in medical and health studies, and to a lesser extent, the tourism literature, on the significance of voluntary international mobility for health- and medical-related reasons (the ‘working definition’ used here) (Hall 2011a). Also of significance though is the realisation that approximately 60 per cent of all journal articles on medical tourism had been written in the two years (2010–2011) prior to the publication of this chapter, while other subjects that seemingly have some profile in the media such as ‘dental tourism’, ‘surgery tourism’, ‘fertility tourism’ or ‘transplant tourism’ have only recently become subject to substantial academic reporting and scrutiny.

What the expansion of writing on medical and health tourism does not immediately reveal is the wide range of perspectives and philosophies that surround the subject and the controversy and debates that have arisen (Hall 2011a). Indeed, the field is one that arguably provides a mirror for some of the wider debates in society as to the limits of the market, the role of regulation and the rights of individuals. It is also one in which academic writing, opinion and influence has perhaps not been subject to the same degree of ethical scrutiny and reflexion as some of the topics under review.

This first chapter aims to provide a brief overview of the academic study of medical and health tourism in order to provide a context for the following chapters and builds on a recent review by the author (Hall 2011a) as well as other recent studies of the subject (Connell 2011). If first discusses some of the issues surrounding definitions of health and medical tourism and proposes a framework to indicate their interrelationships. It then goes on to identify some of the key issues and debates in medical tourism before providing an outline of the book.

Defining health and medical tourism

Health tourism was defined by the International Union of Tourist Organizations (IUTO), the forerunner to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), as ‘the provision of health facilities utilizing the natural resources of the country, in particular mineral water and climate’ (IUTO 1973: 7). Goeldner (1989: 7) in reviewing the international health-tourism literature, defined health tourism as ‘(1) staying away from home, (2) health [as the] most important motive, and (3) done in a leisure setting’. Goodrich and Goodrich (1987: 217) and Goodrich (1993, 1994) defined health tourism in terms of the narrower concept of health-care tourism as ‘the attempt on the part of a tourist facility (e.g. hotel) or destination (e.g. Baden, Switzerland) to attract tourists by deliberately promoting its health-care services and facilities, in addition to its regular tourist amenities.’ More recently, Laesser (2011) suggested that health travel is among the fastest growing tourism market segments and is being driven by five main changes in society:

Table 1.1 Articles on medical and health tourism and cognate terms in Scopus database 1963–2011

Accessed January 2012.

• shifts in demographic structures as well as lifestyles and an active aging population;

• the need for stress reduction among the working population;

• a shift in the medical paradigm towards prevention and alternative practices;

• increased interaction between public health and health psychology;

• the shift from mass tourism towards customised forms of travel.

Nevertheless, even given its economic and social significance, Laesser (2011) did stress that health tourism ‘is (still) a niche and special interest market’ although it did appear to be increasing, noting that in 2004 5.8 per cent of all domestic and international tourism trips of Swiss residents could be considered health oriented, up from 3.3 per cent in 2001 and 1.9 per cent in 1998. Unfortunately, readily comparable statistics are not readily available from other jurisdictions.

Goeldner (1989) suggested that there are five components of the health-tourism market, each relating to a more specific market segment which can have categories of health-related tourism attached to it:

1 sun and fun activities (leisure tourism);

2 engaging in healthy activities, but health is...