- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Previous research has generally shown a very small although statistically significant economic benefit from attending high-quality colleges. This small effect was at odds with what students' college choice and various social theories would seem to suggest. This study sought to reconcile the empirical evidence and theories. The effort was in two directions. First, the economic effect of college quality was expanded from examining only the economic benefit to considering other student outcomes including job satisfaction and graduate degree accomplishment. A new perspective regarding the social role of college quality was offered in conclusion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Does Quality Pay? by Liang Zhang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

American higher education has experienced massive expansion in the 20th century, especially over the last 40 years. In 2000 there were approximately 4,200 institutions of higher education in the United States and its territories, enrolling about 15.3 million students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003). These institutions included 2,450 four-year colleges (enrolling approximately 9.4 million students) and 1,732 two-year colleges (with about 5.9 million students). The diversity of this large enterprise was extraordinary, ranging from two-year colleges providing mainly vocational training and preparing students for further education to large research universities offering a variety of education and research. As the majority of high school graduates in the United States attended colleges, the differentiation of educational attainment increasingly went beyond the dichotomy of college graduates versus non-college graduates. This reality encouraged differentiation among college graduates, with one dimension being college quality.1

Whereas college quality appeared to have profound effects on some student outcomes, graduates’ earnings have long been the particular interest of the research community in the finance of higher education and in labor economics. Many researchers, in one way or another, have made the case that college quality was an element in the formation of human capital and thus had an important effect on earnings. Weisbrod and Karpoff (1968), Reed and Miller (1970), Solmon (1973, 1975), and Wise (1975) were among the first to explore the effect of college quality on graduates’ earnings. Behrman and Birdsall (1983) showed that quantity alone was not sufficient to capture the return of education and that quality should be incorporated into the standard Mincerian (Mincer, 1962, 1974) framework.2 Recently, studies by Brewer and his colleagues (Brewer & Ehrenberg, 1996; Brewer, Eide, & Ehrenberg, 1999; Eide, Brewer, & Ehrenberg, 1998) and Thomas (2000a, 2003) have significantly improved our understanding of the economic effect of college quality.

Implicitly or explicitly recognized in these studies was that the quality of college education, in addition to college education itself, might have significant effects on graduates’ earnings. Most studies along this line, however, found that college quality generally had a very small though statistically significant effect on earnings (Mueller, 1988; Solmon & Wachtel, 1975; Thomas, 2000a). A similar conclusion was drawn by Pascarella and Terenzini (1991) in their review of the literature on the effect of college quality on earnings.

These empirical results appeared to be at great odds with decisions made by many students and their families: If college quality had such a small effect on earnings, why were so many more than willing to pay the increasingly large tuition charges at high-quality colleges? Why did so many work so hard to gain admission to high-quality colleges? For example, for the top 15 liberal arts colleges nationally, the “sticker price” or stated tuition level was $18,057 in 1994–1995, with other institutions (including 2,739 four-year institutions) charging about $5,919 (Ehrenberg, 2000). In 2000–2001 the average tuition rate of Ivy League institutions was about $25,350, while other institutions charged about $8,000, on average. Despite their extraordinarily high tuition rates, the acceptance rates at these elite institutions were surprisingly low. According to US News and World Report, in 2000–2001 the average acceptance rate at the top 15 liberal arts colleges was 35%, and the figure was 18% at Ivy League institutions. The high demand for these high-priced seats at prestigious institutions suggested a larger effect of college quality than has been shown by the bulk of previous research.

Further, the empirical results from previous studies were inconsistent with the disproportionate representation of graduates from high-quality colleges (especially private, elite institutions) among those generally considered to be “most successful” in the United States. National leaders almost without exception held degrees from highly selective private institutions—the Adamses, Roosevelts, Tafts, Kennedys, and Bushes in politics and the Mellons, Rockefellers, and Fords in economic affairs. This evidence was not just anecdotal. In a study investigating the predictors of executive career success, Judge, Cable, Boudreau, and Bretz (1995) found that nearly 1 in every 10 executives was from an Ivy League university, not to mention those from other high-quality institutions. This evidence suggested an enormous impact of high-quality colleges, especially the most prestigious institutions, on social status and power, if not income.

Finally, the results were in conflict with what social theories would suggest. Many social theories would suggest great benefits associated with attending high-quality colleges. From the economic perspective, the decision to choose high-quality colleges, which often meant paying high tuition and fees, was based on a comparison of the financial benefits and costs of such an investment. Considering the substantial tuition difference between high-quality colleges (especially high-quality private colleges) and low-quality ones (especially low-quality public colleges), one would expect significant earnings differences between graduates of these two types of institutions. Human capital theory, a major theory in explaining success in labor markets, also argued for large economic benefits associated with a high-quality college education. The theory posits that the labor market rewards investments individuals make in themselves (e.g., their education or training) and that these investments lead to higher salaries (Becker, 1964, 1992; Schultz, 1960, 1961). High-quality colleges, which usually possess quality academic faculty, capable and motivated students, large libraries, well-equipped laboratories, and so on, appear to provide their students with better resources for human capital improvement than low-quality colleges.

It seems, then, that empirical evidence is not fully consistent with everyday observations and social theories. Can these observations and theories be reconciled with the empirical evidence? What is the role of college quality in society? Answering these questions is the goal of this study.

To achieve this goal, I broaden the research on the effects of college quality on earnings by examining the variability in the effect of college quality along an array of factors. Whereas previous research has evaluated the effects of college quality at the mean of the earnings distribution, I consider the effects more broadly. Implications and applications of mean results or “average” effects are based implicitly on the assumption that the monetary effect of college quality is homogenous across different students. This assumption is convenient but potentially problematic. Intuitively, it is probable that college quality may matter to some students but not to others. For example, it may be that it is more productive (greater “value added”) for a more capable student to study at an elite institution than for one who is intellectually less capable. Therefore, empirical results stated at the average may mislead many students and their families. If it can be shown that substantial differences in earnings exist among particular groups of students enrolled in colleges of varying quality, then the results of prior studies, although presumably valid on average, may lead to invalid generalizations with regard to specific individuals and specific colleges.

Also, I extend the study of the effects of college quality beyond the area of earnings differences. Most previous studies on the effect of college quality have ignored the effect of college quality on non-monetary outcomes. Bowen (1977) suggests that a college education might have effects on a variety of non-monetary outcomes. So too might college quality have effects on various non-monetary aspects of students’ lives. Due to lack of data and other limitations, an inventory of such non-monetary outcomes is apparently impossible. In this study, I consider the effects of college quality on two non-monetary outcomes: graduate education and job satisfaction. (Graduate education is a particularly interesting outcome in that it may in turn have positive effects on earnings.) If it can be shown that college quality has a positive effect on nonmonetary outcomes, such as graduate education and job satisfaction, then focusing on economic benefits alone could understate the real effects of college quality. Significant and positive effects of college quality on non-monetary outcomes may add considerably to the relatively small, average, monetary effects of college quality and in the process bridge the gap between social theories and prior empirical results. By expanding the previous research on the effects of college quality in these two directions, my ultimate goal is to explore a new perspective on the impact of college quality, especially to certain groups of students.

The organization of this book is as follows. In Chapter Two, I review the literature on the effect of college quality on earnings and argue that the average effect of college quality as examined in previous studies disguises much of the variation in the effect of college quality across individuals and overlook the non-monetary outcomes. I then provide the theories that guide the inquiry into the variability in the effects of college quality. Specifically, I discuss two representative theories: human capital theory, which, from a rational perspective, accentuates the positive role of education on individual economic outcomes, and social reproduction theory, which, from a critical perspective, highlights the interaction between socioeconomic status and educational attainment. The discussion of social reproduction theory leads to three research questions and corresponding hypotheses, which are analyzed and tested in subsequent chapters.

In Chapter Three, I focus on degree attainment by examining the variability in the probability of earning degrees at high-quality institutions. The probability may vary across individuals due to various academic and non-academic factors. Further, these academic and non-academic factors may be related to each other in certain ways. Analysis in this chapter situates the discussion of the variability in the effects of college quality across individuals in a proper context. These are two different equity issues, but both should be considered in understanding the role of college quality in particular and education in general in society. Focusing on the varying effects of college quality among individuals without examining the varying probability of earning degrees at high-quality colleges does not capture the complete relationship among socioeconomic factors, educational attainment, and graduates’ earnings.

A series of questions is posed in this chapter. For example, how is the probability of earning a degree at high-quality institutions related to students’ demographic characteristics? What is the effect of family background? Does student ability play any role? If so, how is student ability related to demographic and family background characteristics? These research questions point to larger issues of post-secondary access and baccalaureate attainment; more importantly, they provide a proper context for thinking about different effects of college quality for different individuals.

In Chapter Four, an empirical model is established to estimate the average effect of college quality on graduates’ earnings. The estimated effect is on average in the sense that there might be variations among different groups of students and across different points of the earnings distribution. This model has been discussed and tested by other researchers and myself in previous studies of the effect of college quality (Thomas, 2003; Thomas & Zhang, 2005). Then I investigate some issues related to the model before it is applied to specific groups of students in Chapter Five. These issues include different measures of college quality, earnings growth over time, correction for selection bias, and Hierarchical Linear Modeling.

In Chapter Five, I explore the variability in the effects of college quality among different individuals by gender, race/ethnicity, family income, parental education, intellectual ability, and major fields of study. Essentially, the question here is whether different students are able to realize the same amount of economic benefit from earning degrees at high-quality institutions. Examining the difference in the effect of college quality among different individuals helps explain the social role of college quality, and varying effects of college quality across different individuals are crucial in understanding the social role of college quality.

In Chapter Six, I consider the other dimension of the variations in the effect of college quality, that is, variation across the earnings distribution. For example, do high-quality colleges affect students who end up at the bottom of the earnings distribution more than those who end up at the top of the earnings distribution? In other words, does college quality compress or stretch the earnings distribution? These questions point to the different predictive power of college quality for individuals at different positions in the earnings distribution. Put simply, college quality may matter more for students who end up at the top of the earnings distribution than those at the bottom. In an era when college education becomes quite universal and, more importantly, as previous research has shown that college education tends to compress the earnings distribution (Eide & Showalter, 1999), the role of college quality as a differentiating apparatus needs to be examined properly.

The analysis of the effect of college quality on graduates’ earnings would not be complete without examining the effect of college quality on graduate study. The benefit of attending colleges of higher quality is more than earnings premium; it may involve the opportunity to obtain further education, which in turn yields a positive economic effect. This idea is framed as the option value by Weisbrod (1962). If it can be shown that college quality has a positive effect on graduate education and moreover that graduate education has a positive effect on earnings, then estimates of the effects of undergraduate college quality based on earning differences among terminal baccalaureate recipients is most likely underestimated. In Chapter Seven, I study the effect of college quality on graduate school enrollment and graduate degree attainment. For example, how does the quality of college attended affect a student’s decision to enter and complete a graduate degree program? For those who have actually enrolled in graduate programs, how does college quality affect the program type, specifically a master’s versus doctoral program? And what is the effect of college quality on the selection of graduate institutions, that is, comprehensive, doctoral, or research institutions?

In Chapter Eight, I investigate the effect of college quality on another non-monetary aspect of student outcomes, job satisfaction. The effect of college quality on job satisfaction is not clear-cut. On one hand, College quality may have a positive effect on job satisfaction by raising graduates’ earnings. On the other hand, college quality may be related to how well one’s occupational expectations are met, possibly resulting in a negative job satisfaction effect. Whereas the small number of studies that have addressed this question suggest that college quality has little direct effect on an individual’s job satisfaction (Bisconti & Solmon, 1977; Ochsner & Solmon, 1979; Solmon, Bisconti, & Ochsner, 1977), these studies have tended to suffer from several weaknesses, including inadequate job satisfaction measures, inappropriate treatment of the categorical dependent variable, and neglect of the endogeneity of earnings. My analysis seeks to overcome these shortcomings.

From Chapter Three to Chapter Eight, I provide an examination of the entire process of post-secondary attainment—from baccalaureate attainment to graduate education and to outcomes in labor market at the early stage of graduates’ careers. Throughout this process, college quality is the element of particular interest. The effect of college quality and the role of high-quality institutions may be better understood in the larger frame of post-secondary attainment.

In the concluding chapter, I sum up all the findings of this study and turn back to my starting point: What have we learned about the effect of college quality from this study? In summarizing my major findings, I discuss variations in the effect of college quality, suggesting that the average economic effect of college quality as estimated in previous studies disguises many variations of the effect across an array of factors. Moreover, I examine the social role of college quality by integrating various components of the analysis in this study, arguing that college quality plays an important role in preserving and perpetuating socioeconomic structure in American society. Finally, I explore the policy implications of this study for educational practitioners and policy makers.

Chapter Two

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Generally speaking, the modern literature on the economic effect of college quality began with studies by Weisbrod and Karpoff (1968), Wales (1973), Solmon and Wachtel (1975), and Wise (1975) and recently has undergone a renaissance with works by Behrman, Rosenzweig, and Taubman (1996), Brewer and Ehrenberg (1996), Brewer et al. (1999), and Dale and Krueger (2002). Pascarella and Terenzini completed a summary and criticism in 1991. Not only were the results of studies of these issues important for academic and theoretical purposes, they were also important to prospective students and their parents who paid more of the increasing costs of higher education, especially at prestigious institutions (Ehrenberg, 2000).

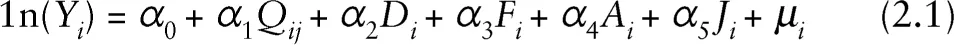

Table 2.1 summarized 24 previous studies of the effect of college quality on earnings. Although the list was by no means exhaustive, it included most of the published, methodologically rigorous studies. Twelve of these studies have been summarized in Brewer et al. (1999). Almost without exception, studies in Table 2.1 used more or less the same methods: Individual i’s log earnings or hourly wage rate (ln(Yi)) was a function of the quality of institution j he or she actually attended (Qij), demographic characteristics (Di), family background (Fi), academic background (Ai), job market conditions (Ji), and an individual disturbance term (µi). In mathematical notation,

Table 2.1 Summary of Previous Studies of the Effect of College Quality on Earnings

* Studies with * are summarized in Br...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter One Introduction

- Chapter Two Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

- Chapter Three Who Completes at High-Quality Colleges?

- Chapter Four The Economic Effect of College Quality

- Chapter Five Variability in the Economic Effect of College Quality1

- Chapter Six College Quality and Earnings Distribution

- Chapter Seven College Quality and Graduate Education1

- Chapter Eight College Quality and Job Satisfaction

- Chapter Nine Summary and Discussion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index