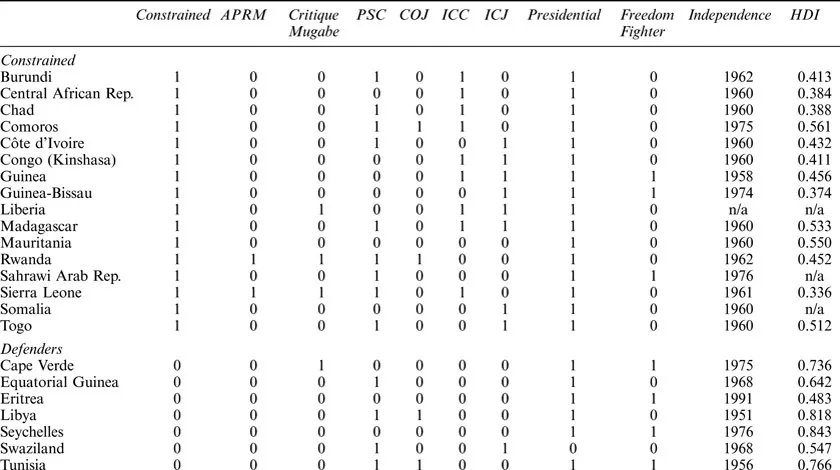

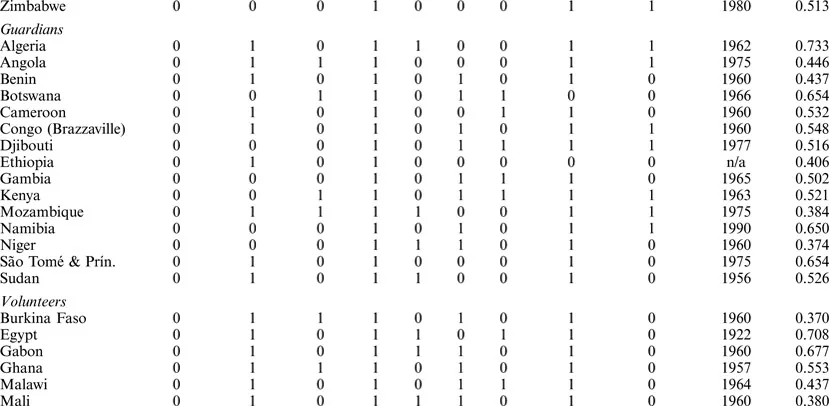

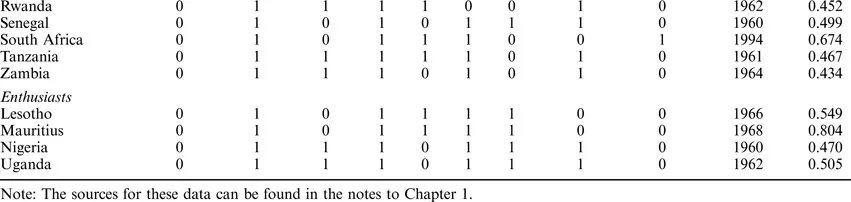

There are 54 states in Africa including the Sahrawi Arab Republic.1With the exception of Morocco, all these 54 countries are member states of the AU and thus form the research object of this study. It would be impossible to conduct a comprehensive qualitative study that examines all 53 countries; hence, selection is required. The case selection was carried out in two steps: first, the AU member states were grouped according to their willingness to pool sovereignty. Various variables indicating the willingness to transfer sovereignty were used to categorize the states into four groups: the Defenders, the Guardians, the Volunteers, and the Enthusiasts, plus an additional group, the Constrained, the reason for which is explained below. This categorization was done to ensure that the study depicts the whole variance of AU member states in respect to their (un)willingness to cede sovereignty, and hence, provide the most complete picture possible. In a second step, two cases were selected within each of the four groups according to a most-different-system design.

Before continuing to define the grouping, some technical details for the case selection are provided: the data used for the categorization were collected in June–August 2008 and were partly updated toward the end of 2009. All data are provided in Table 1.1. The names of the relevant variables are noted in brackets in this chapter, and further details on them can be found in the notes. All variables for the first step in the case selection are dichotomous; they hold the value 1 if they indicate “yes,” and 0 if they indicate “no.”

Grouping the African Union members

The study analyses four groups of states along a spectrum that ranges from states that are completely unwilling to surrender sovereignty to states that show willingness to cede sovereign rights. The first group includes states that are largely unwilling to surrender sovereignty, the Defenders.

Table 1.1 Data used for the case selection

The second group, the Guardians, are similar to the Defenders, yet appear slightly more willing to give up sovereignty. The Volunteers, as the third category, show an even greater willingness to cede sovereignty and are only excelled in their willingness by the Enthusiasts, who have little desire to protect their sovereignty and are the most willing to transfer it.

In addition to this spectrum, a fifth category was excluded from the analysis. The Constrained group’s main characteristic is their a priori assumed inability to engage in international affairs, which results from circumstances that severely constrain state action.2 Such circumstances include either being occupied and governed by an external power or having vital domestic issues to solve such as post-conflict reconstruction, a large scale civil war covering large parts of the territory, a peace-keeping mission, or a recent coup d’état. It is assumed that such internal problems make it difficult, if not impossible, to provide resources and engage in the AU. In short, the Constraineds are too busy dealing with their internal issues and therefore do not have the capacity or the means to engage in the continental integration process. Thus, all states that are not self-governed or have had a war or experienced a coup d’état within the last five years were excluded from this study as it does not seem beneficial to explore countries that seem a priori unable to engage in the continental integration process.3

The first step in the categorization was straightforward. Each country was determined as being either constrained or not: if a country could be considered as Constrained for one of the above reasons, the country was classified as Constrained irrespective of other variables.

Naturally, grouping countries into the other four categories depends on how willing a country is to cede sovereign rights. To decide this, seven variables were used. The first variable is their participation in the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), a mechanism that inter alia monitors and evaluates achievements in terms of democracy, good governance, and rule of law.4 “At many levels, the APRM is an exceptional undertaking. For the continent that had jealously protected its sovereignty, it is diplomatically exceptional for nations to throw themselves open to outside scrutiny.”5 Against this background, it is noteworthy that more than half of AU members have joined the APRM (28 out of 53) at the time of data gathering.

Participating in this monitoring mechanism, however, does not reveal whether the country would either accept the critique received from the monitoring process or implement the proposed plan of action. Thus, the variable APRM must be accompanied by a further variable that provides information about the influence of the APRM. Such a variable would consequently be the acceptance of the APRM’s critique and the willingness to implement the plan of action. However, there are two problems attached to this: first, it is not easy to determine whether the states have implemented their plans of action; this would require an individual study for each case. Second and more important, only a few of the states that have joined the APRM have managed to complete the whole monitoring and evaluation process. This is because it takes several months—or even years—to complete the research, hold discussions, and publish the report. The variable is therefore impractical and an alternative variable is required.

As such, having criticized Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe during the highly contested presidential election in 2008 offers an appropriate alternative (CritiqueMugabe).6 Criticizing Mugabe’s undemocratic behavior is clearly associated with the question of whether a state feels committed to the democratization efforts made by the APRM and, more importantly, whether this state would accept interference in its internal affairs. Therefore, this, the second variable, provides a good indication as to whether a state would accept the APRM critique. As the Zimbabwe case was debated heatedly at the AU Sharm el-Sheikh summit in July 2008 and was also on the agenda at the European Union–AU summit in Lisbon in December 2007, it is safe to assume that the Zimbabwean crisis has become a continental issue and its impact is not only restricted to southern Africa. Obviously, this variable is not the same as the acceptance of the APRM critique, yet it is an appropriate substitute.

The third and the fourth variables are the states’ membership of the AU’s Peace and Security Council (PSC)7 and the AU’s Court of Justice (COJ).8 The latter is a kind of constitutional court for the AU. Joining it supposedly means obeying the jurisdiction of that court. The PSC works in a similar way to the United Nations Security Council. Almost all AU member states have ratified the protocol establishing the PSC. It seems opportune among African states to join the council. Both variables are important and provide some insight into a state’s willingness to give up sovereignty in the AU context; however, they do not hold as high a value as the APRM variable. Participating in the APRM requires a strong commitment to the AU and its principles and, consequently, a greater willingness to surrender sovereign rights than joining the PSC or the COJ. As such, the APRM variable is double weighted. If a state is part of the APRM and has criticized Mugabe, it is even triple weighted.

So far, only Africa-internal variables have been introduced. Additional global variables are required to build a more comprehensive picture. Therefore, it is asked whether a state accepts the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as compulsory by ratifying the relevant treaty.9 Obeying the jurisdiction of the ICJ means sustainably surrendering sovereign rights as the adjudication of the court is then binding. Equally, ratifying the statute that establishes the International Criminal Court (ICC) means losing some of the sovereign rights of a state.10 Instead of prosecuting a war criminal in the domestic courts or tribunals, for example, preference is given to the ICC to fulfill this task. Considering the ICC’s and the ICJ’s jurisdiction as mandatory is effectively equivalent to a high level of willingness to cede sovereign rights; thus, both the ICC and the ICJ variables are double weighted.

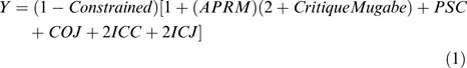

If this is translated into mathematics, the following equation can be produced:

Equation 1 is set up in such a way that all states considered to be Constrained score 0. This score and threshold are intuitively right. For the other groups, the obvious rule is that the higher the score, the greater the willingness to yield sovereignty. A state should be considered a Defender if it will not give up sovereign rights other than for its own survival or because it is opportune. To set the threshold at a maximum value of 3 leaves the possibility open that a state shows a waiver of sovereignty in one or two of the above variables, but does not indicate a willingness to surrender sovereignty in other fields. For example, it has become a modus vivendi for African countries to join the PSC. At the time of writing, only 10 out of 53 states have not yet ratified the protocol. It is important to leave the PSC as a variable in the equation, yet the thresholds need to be defined in a way that takes this modus vivendi into account.

A Guardian watches its sovereignty carefully; it surrenders it only partially. There are some cases where sovereignty is only given up in the African realm, but not for the ICC and ICJ. In other cases, sovereignty is only given up in the global realm while protecting it and holding up the doctrine of non-interference vis-à-vis fellow African states. All these states are Guardians, as they do not show a consistent willingness to surrender sovereignty.

A state must cede sovereign rights in both the African realm and the international realm to obtain the status of a Volunteer or an Enthusiast. With a score above 7, this is the case. The threshold between Volunteers and Enthusiasts is set at 9. To obtain a score of 9 and above requires an engagement in both dimensions, to obey international jurisdiction and to leave behind the doctrine of non-interference in internal affairs at a continental level. In other words, sovereign rights are ceded at a high level, indicating a consistent willingness to relinquish them. Table 1.2 shows the results of the categorization and provides the score for each state.

Selecting the case studies

In the second step of the case selection, two states within each group (except from the Constrained) were selected according to a most-different-system design. The latter helps to uncover explanatory variables and can help to develop hypotheses by comparing each group’s most-different members with regard to the independent variable. Depicting the variance of AU members with regard to their (un)willingness to cede sovereignty and using a most-different-system design offers a good chance of uncovering patterns that explain why AU member states are (un)willing to yield sovereign rights.

To select the cases according to a most-different-system design, it is necessary to have some possible explanatory variables in mind, according to which the ultimate case selection is made. The following list of variables draws on the conjectures mentioned in the introductory chapter. It is assumed at the outset that the length of time elapsed between independence and today, the way the country gained independence,11 and whether today’s political leadership were part of the liberation struggle12 might be explanatory variables for comprehending why a state is (un)willing to cede sovereignty. Additionally, the political system itself could play a role, as it can be assumed that the way the political system is designed, giving greater or less power to the head of state or government, can help explain a specific position with regard to the surrendering of sovereignty.13 Lastly, socio-economic status might play a role; poorer states might be forced to integrate as they cannot overcome their structural problems alone and hence cede sovereignty, whereas richer states see less need to integrate with their neighbors, which are often poorer and thus of little help in boosting their own economy.14

For the Defenders, Swaziland stands out as an untypical case. Contrary to the other states in this group, it does not have a presidential system; instead, it is a rare case of an African monarchy, and its current leader was not part of the liberation fight. As matter of fact, Swazis never fought for their independenc...