eBook - ePub

Retailing (RLE Retailing and Distribution)

Shopping, Society, Space

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This textbook provides an up-to-date, comprehensive and fully integrated treatment of retailing as a) and industry, b) a force shaping social attitudes and contemporary culture, and c) a force for change in modern townscapes. Unlike other texts which focus on specific topics, this book provides a treatment of retailing which will appeal to geographers, economists, planners and social scientists.

First published 1991.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Retailing (RLE Retailing and Distribution) by Larry O'Brien,Frank Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Retailing: Economy and Society

Introduction

The function of a retailing system is to supply goods and services to meet the needs, wants and desires of the public. In Britain, this public lives mainly in towns and cities and exchanges its labour for work in shops, offices and factories. Very few people live an entirely self-sufficient life out in the country (Hudson and Williams 1986, Cater and Jones 1989). Britain has been a predominantly urban-industrial country for well over one hundred years but the character of its towns and cities and the employment they offer has changed dramatically since the Second World War. Work in agriculture and manufacturing has declined rapidly, deepening existing structural difficulties for those regions relying on them. At the same time the supply of work in service industries such as retailing has been steadily increasing, so that today, services and new information-processing industries based on the use of computers and telecommunications account for well over half of the working population (Hepworth 1989).

This restructuring of the British economy has been accompanied by a restructuring in the world economy. The Second World War crippled Europe — the traditional heartland of international capitalism — and allowed the mantle of authority over world markets to pass to the USA. They, in turn, have allowed it to pass to Japan, though competition from other countries in South East Asia, a rejuvenated European Community and a potential US-Canada-Mexico free trade zone (Charles 1989) may make it difficult for them to hold it for long. As a subsidiary member of an increasingly global economy, 1990s Britain is much less capable of looking after her own affairs than in the past. The tempo of the economy is dictated both from within and without. Britain’s manufacturers now rely heavily on global sourcing of goods and materials (Dicken 1986). Britain’s retailers increasingly sell products made both at home and abroad, bought from multinational corporations whose production bases can be footloose and whose commercial visions are global in extent (Frobel et al 1980). This is the commercial context in which Britain’s retailers operate and which underpins the sorts of retailing they provide.

The aim of this chapter is to describe contemporary British needs, wants and desires and to show that they are related to the state of the national and international economies. It begins with a brief resume of the state of 1990s Britain, focusing on work, society and changing patterns of consumption. Some attention is then given to defining the term ‘needs’ and discussing how they are created by societies. As British needs are mainly urban needs, this means considering some of the relationships which exist between urbanisation, production and consumption. The chapter concludes with a discussion of Abraham Maslow’s model of psychological needs. This suggests that in ‘advanced’ societies, personality and motivational needs (‘learning to live to my full potential’) become paramount for the individual. This has important implications for the processes of market segmentation which are crucial to a contemporary description of British retailing.

The state of contemporary Britain

Work

The term ‘work’ is formally used to refer to that process where individuals exchange their time and labour for a weekly pay packet or a monthly salary cheque. Going to work involves the movement of people from their homes to workplaces and has considerable implications for land use, transport and the quality of life. People who exchange their time and labour are ‘workers’, those providing work are ‘employers’, and the purpose of the whole exchange is the ‘production’ of goods and services. These goods and services are produced to be ‘consumed’. Consumers may include government, commercial organisations, public services, foreign companies and households. Frequently, goods and services are consumed by those workers whose purpose is to produce them in the first place. The whole process is circular with workers as consumers relying on workers as producers to meet their everyday needs.

This type of system can be an enormously powerful arrangement which significantly increases the number and diversity of goods and services available to the public. However, it depends on the workers accepting their roles and playing their parts. Such a system is not natural or ‘god-given’ but is one created to meet specific economic ends by particular organisational means. Key among these has been the extensive division of labour which has led to an intense specialisation in types of work and in the creation of designated places of work such as factories and business districts. Such specialisation implies that no individual or firm is entirely self-sufficient, but is locked into a complex web of economic interrelationships with other individuals or firms to meet their needs. The resulting process of exchange between individuals and firms provides the motivation for the creation of a system of retailing.

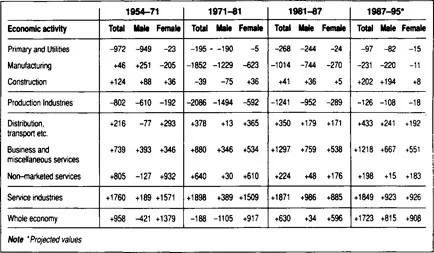

The system described above is based on formal relationships between employer, worker, government and other interested parties such as employers’ and workers’ organisations. The present employment structure of Britain (Table 1.1) has evolved over time from one based predominantly on the primary sector (agriculture, quarrying, mining, fishing and forestry). This was followed by an industrial period when the bulk of the workforce was involved in manufacturing.

In the postwar period, Britain has seen some major changes in its industrial and occupational structure. De-industrialisation has led to employment decline in manufacturing, initially in industries such as clothing, textiles, leather goods and shipbuilding, but thereafter, more widely. Accompanying this have been changes in government policies which have moved away from the post-war preoccupation with full employment to the contemporary concerns for the management of inflation. A significant restructuring of the economy has followed from this which has favoured the growth and development of service industries covering public consumption (health and education), private consumption (retailing) and producer services (business and financial services). Figures published in the Labour Market Quarterly Report (May 1990, p. 2) show that in the year to December 1989 the number of service employees increased by 534,000 compared with

Table 1.1 Change in employment by broad economic activity in the United Kingdom 1954–95. (Figures in thousands)

(Source: Compiled from Table 4, Review of the Economy and Employment, Institute for Employment Research, 1988–89. Vol. 1)

the 490,000 increase in all other industries. Banking and financial service employment grew by nearly 8% over the same period compared with the nearly 6% decline in agriculture. These changes have been associated with a growth in real disposable income. Between 1981 and 1988, real disposable income rose by 25%. Median gross weekly earnings for full-time male employees have risen considerably since the 1960s. Figures reported in the New Earnings Survey were £188 for manual workers and £260 for non-manual workers. The equivalent figures for 1971 were £28 and £34 respectively. Figures for full-time female employees were £116 and £157 in 1988 compared with £15 and £18 in 1971.

Formal employment is not, however, the only form of work arrangement one can find in contemporary Britain. Gershuny (1978), and Pahl (1984) draw attention to the workings of an ‘informal’ economy in which the nature of work and the jobs which go with it are defined not by government classifications but by social groups themselves. Frequently such work is conducted outside the formal arrangements of legal contracts and VAT, with ‘payment’ being either in cash or in kind.

The figures listed in Table 1.1 show that among those in formal employment the lion’s share is increasingly being taken by the services sectors — what have been termed the ‘post-industrial’ sectors of an economy (Bell 1973, 1980). Bell suggests that developments in information technology — computer-controlled telecommunications — lie at the core of the modern economy and society and that this is

decisive for the way economic and social exchanges are conducted, the way knowledge is created and retrieved, and the character of work and occupations in which men (sic) are engaged. (Bell 1980, p. 532)

In Bell’s model, the traditional sectors of the economy — primary, secondary, and tertiary — are replaced by three alternative foci defined to show the penetration of information-craft throughout all economic activity: extraction, fabrication and information activities.

The key elements of information technology are computers, telephones, facsimile transfer systems, cable and satellite television, and video disks. Increasingly the machinery operating these services is becoming more integrated, leading Bell to suggest that there will be

a vast reorganisation in the modes of communication between persons; the transmission of data; the reduction if not the elimination of paper in transactions and exchanges; new modes of transmitting news, entertainment and knowledge. (Bell 1980, p. 533)

He anticipates that all these developments will open the way for mankind to pursue individuality while benefiting from a vastly increased supply of goods and services. The key to this good society is the ability to produce for increasingly diverse consumption patterns while freeing many of the workers from the need to work. David Bolter (1984) goes even further: he sees computers as ‘defining technologies’ which bring about transformations in the human sense of self. Humans come to see themselves as ‘information processors’ and nature as ‘information to be processed’. With humankind redefined in terms of machinery, our social needs are likely to be redefined too.

The problem with both the post-industrial and the information societies is that they are ‘chaotic conceptions’ — rag-bag classifications which cut through social relationships with little concern for meaning. As Lyon (1988) correctly points out, the statistics which note that 60% or more of the population work in information related jobs do not place these people in social contexts. Information jobs are variable, including data analysts and information consultants at one end to data preparation staff (glorified typists) at the other. The output from information work may vary from financial reports to lectures, or from computer bulletin boards to free newspapers. There is no clearly-defined account of how information work differs from other type of work. The range may also conceal significant gender differences with female employment in informatics being ghettoised towards the lower end. This is a point also taken up by Miles and Gershuny (1986) who suggest that information work has a multitude of different meanings. The future of the post-industrial and information societies will not be led by technology, they argue, but by political decisions made by people who may have come to rely on technology. The two are not the same.

Retailing is noted for its reliance on information, particularly on changing tastes and patterns of consumer behaviour. Commercial pressure has forced the major retailers to invest heavily in information technology, both in-store (for example, in computer-controlled check-outs) and for stock control in their warehouses. Information technology has created new employment opportunities in retailing with the growth of the career professional whose job is information management and forecasting. Few of these work on the shop floor. The majority of shop workers who are in regular contact with the public are women, many of whom are employed part-time. Their jobs frequently require them to use advanced computer-controlled equipment such as laser-scanner check-outs, which can be used successfully after minimal training. The levels of skills needed in shop-floor workers has fallen as a result with significant deskilling in some areas. Some of the issues associated with retailing and the post-industrial society are taken up in more detail in Chapter 7.

Society

Britain has undergone many changes in its social structure since the Second World War which are reflected in the ways social needs and desires are created. A major factor has been the considerable increase in public consumption allied to the development of the Welfare State. Not only has this provided opportunities for new types of work in health care, social services and education, many of which have been taken up by women, but it has also changed attitudes towards the domestic division of labour and family life.

Of particular significance has been the growing acceptance among young people of new forms of family formation. Whereas previously, the traditional model of the British family was of a household consisting of two parents and dependent children, recent figures from the General Household Survey for 1988 show this to be only one of a number of competing alternatives for the 1990s (OPCS Monitor 5th December 1989). Today, only 26% of households fall into this traditional model. The largest grouping at 36% is married or cohabiting couples without children or with non-dependent children (frequently multi-income households). Indeed, cohabitation for women aged 18–49 doubled between 1981 and 1988. Single person households make up 26% of British households and lone parents a further 12% of all households surveyed. Britain currently has the highest marriage and divorce rates in the European Community.

One of the key changes which underwrites many of the developments in British retailing is female employment in paid work outside the home. Opportunities for female employment have increased considerably since the Second World War and this had led to financial independence for many women and the desire to place a career before child-bearing. Of the 26.5 million workers in Britain in December 1989, nearly 12 million are women of whom 5 million work part-time. Labour force projections to 2001 suggest that the number of female workers will increase to approximately 13 million, whereas the numbers of males in employment will remain much the same. Self-employment among female workers (6.6%) is however considerably less than among their male counterparts (16.8%). The implications for domestic life are considerable in that many jobs previously thought to be unpaid ‘women’s work’ (domestic cleaning, child care) are now seen as personal services which can form the basis for new types of employment.

Other data reported in the preliminary results from the General Household Survey for 1988 and in Social Trends indicate other important social changes. The pattern of tenure is particularly interesting with an increasing proportion of personal income being spent on housing. The survey results show that the level of owner occupation continues to rise from 49% in 1971, 52% in 1981, to 63% today. At the same time, the percentage of households renting privately or from local authorities has continued to fall (26% in 1988).

The ability to buy a house depends on employment status, the demand for mortgages and the present and assumed future economic health of the economy. There are considerable regional differences in these variables.

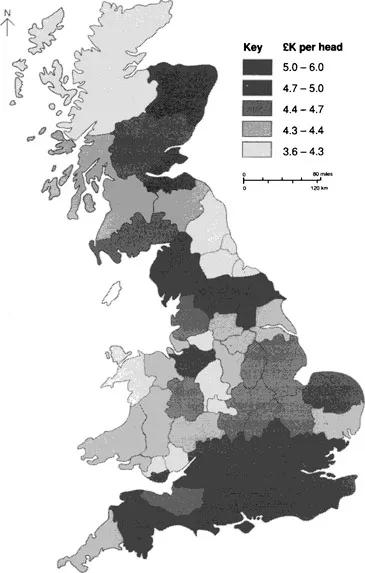

Figure 1.1 Household Disposable Income per head by County/Region (1987)

(Source: Central Statistical Office)

Data published in Economic Trends (April 1990) suggest that the regional differences in the levels of disposable household income are increasing. From 1978–88 total personal incomes rose most rapidly in the South East, South West and East Anglia and declined relative to the national average in the West Midlands, North West and Wales. A proportion of these differences can be explained by changing demographic factors such as the rise in population in East Anglia over the period. However, strikes and the excellent grain harvest in 1983 affected regional incomes in the North, Yorkshire Humberside and East Anglia. Figure 1.1 displays the spatial structure of household disposable income per head (income minus tax, national insurance, life assurance and pension contributions) by English and Welsh county and Scottish region in 1987. Surrey has the highest county level and Mid-Glamorgan the lowest. However, a simple interpretation of the map is not possible because the variations in the spatial distribution of pensioners affects the calculation of household disposable income. Dorset, for example, has a relatively high level of household disposable income per head because deductions are minimised by the large numbers of pensioners living there. For further details of the effects of the elderly on local economies, see Warnes and Law (1984).

Patterns of consumption

The changing social and economic structures of Britain outlined above have been reflected in changing patterns of household and personal consumption. In addition to increased expenditure on hou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title1

- Copyright1

- Full Title2

- Copyright2

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One Retailing: economy and society

- Chapter Two Marketing and retailing

- Chapter Three British retailing

- Chapter Four The geography of supply and demand

- Chapter Five Shops, shopping centres and the built environment

- Chapter Six The modern consumer

- Chapter Seven Information and retailing

- Chapter Eight Green retailing

- Chapter Nine Conclusions

- References

- Index