![]()

1 The fallacy of competition

Markets and the movement of capital

John Weeks

Introduction

Of central importance in the entire neoclassical theory of production, exchange and distribution is “competition”. “Competition” ensures that “consumers” receive “value for money”, “competition” forces producers to lower costs, and thus generates the ultimate benefit of the market system, “choice”. By realizing these benefits, competition generates the best of all economic outcomes, Pareto Optimality.

In the absence of “competition” benefits fade and markets whither. In neoclassical theory, competition is more than just a good thing, is the Philosopher’s Stone of the theory. Touch it to a market and efficiency prevails. When “competition” holds sway in the neoclassical sense, the working of the economy approaches the sublime; when it is imperfect all necessary steps must be taken to purify it.

In the economics profession and in the press, the truth of these arguments is taken as self-evident. Not even the financial crisis of the late 2000s undermined faith in the magic of competition. On the contrary, the major proposals to prevent re-occurrence of the crisis included steps to make financial markets more “competitive”. Rare is the progressive writer who does not argue that the evils of markets derive from monopoly power and would be eliminated or at least reduced by increased competition. This was famously argued by the most prominent American Marxists of the twentieth century, Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy (1966).

It is common for progressives, similarly to the neoclassicals, to attribute the inefficiencies, inequities, and outrages of capitalism to the absence of “competition”. Quite uncommon is when the term is clearly defined and its characteristics specified. Stiglitz, rightly or wrongly considered by most of his colleagues to be a political progressive, states in his introductory book (jointly authored with Walsh), “One of the most fundamental, and perhaps surprising, ideas in economics is that competitive markets are efficient” (Stiglitz and Walsh 2006: 39). Somewhat ambiguous is the position of another Nobel Prize winner considered progressive, Paul Krugman. In his work on trade theory he does not uncritically endorse competition, but his analysis of trade with increasing returns to scale derives clearly from the perfect competition benchmark (Krugman 1985).

Of prominent economists of the twentieth century, few explicitly rejected the neoclassical romanticism of competition, the most notable being John Kenneth Galbraith. Along with his skepticism about the benefits of competition, Galbraith insightfully identified it as inextricably linked to the use of mathematics in economics. Referring to the takeover of economics by mathematics, Galbraith wrote, “In the real world perfection competition was by now leading an increasingly esoteric existences, if indeed, any existence at all, and mathematical theory was, in no slight measure, the highly sophisticated cover under which it managed to survive” (Galbraith 1989: 260). His book The New Industrial State (1967) can be read as devastating critique of the myth of benign competition. However, to describe John Kenneth Galbraith’s view on competition as rare overstates its frequency among economists, left, right, or center.

In this chapter I argue that the benign view of competition is fundamentally wrong. The positive role of competition derives from a purely theoretical construction in which competition is an analytical black box. Neoclassical competition is a fictitious phenomenon constructed with a narrow focus on exchange that is divorced from capitalist relations of production. Placing competition in its appropriate context, as the manifestation of the movement of capital, reveals the analytical poverty of the neoclassical approach, as well as its absurdities. In essence the neoclassical theory of competition is nothing more than a mathematical rendering of the petty commodity production of the nineteenth century romantics of political economy.

Romanticism of competition

Competition in partial equilibrium

Almost 250 years ago, Adam Smith wrote: “In general, if any branch of trade, or any division of labor, be advantageous to the public, the freer and more general the competition, it will always be the more so” (1937: 329). Reading these words literally without nuances, neoclassicals conclude that more competition by their definition is always good. Smith’s approach to competition was a product of the specific historical phenomenon, the Scottish Enlightenment during the early development of capitalism. For Smith and other writers, such as his friend David Hume, “competition” meant the end of feudal institutions such as guilds and a range of communal and landlord rights that constrained the alienability of land.1

Notwithstanding its historically specific context and meaning, Smith’s enthusiasm for competition remains as strong as ever among economists and the person in the street. Not even the financial crisis of the late 2000s undermined faith in competition. It is part of the folklore of economics and business journalism that while perfect competition is impossible, more competition is better than less, just as Adam Smith asserted. A generation ago the flaw in this argument was demonstrated by mainstream economists Lipsey and Lancaster (1956–57). As surprising as it may seem to the non-specialist, neoclassical theory provides no rule for systematically analyzing whether more competition is better than less.2

As explained in the next section, the agnostic conclusion about degrees of competition reflects the lack of an analysis of competition as process. The standard economics textbook presentation typically defines perfect competition to be the result of a large number of relatively small buyers and sellers, each acting on the belief that he or she cannot affect the market price.3 In other words, the market participants consider themselves to be price constrained, not quantity constrained. This common statement about numbers of rivals and the price constrained result is a logical muddle. The number and size of enterprises are characteristics. Whether the firms have an impact on market price is an outcome. The two must be linked by a process. It may seem “common sense” that many buyers and sellers would believe themselves unable to affect price, but theoretical insights do not derive from laboring the obvious.

I begin the critique of neoclassical competition with the simple presentation one finds in introductory and intermediate microeconomics textbooks. After showing the obvious inadequacies of that approach, I move to the realm of high theory, Walrasian general equilibrium analysis. The typical textbook presentation presents competition in a single market or as a partial equilibrium phenomenon. At this level of analysis the existence of competition depends on the specification of the relationship between costs and outputs for the enterprises that produce a product. At the risk of laboring the obvious, it is necessary to go to first principles in order to understand that the neoclassical approach to competition is theoretically vacuous.

In the theory the existence and sustainability of competition among enterprises depends on whether production and market conditions allow for the continuous presence of many independent enterprises. For this to happen, it must be that no enterprise can expand to a market share that would allow it to manipulate the market for the commodity the enterprises produce. A necessary condition to prevent this is that production units have their minimum unit cost at an output level that is a small fraction of market demand when the market price equals that minimum. To achieve this result, unit costs cannot be constant with respect to scale of operation. If that were the case, enterprises would expand until only a few remained. Nor could it be the case that unit costs fall or rise with increases in scale. The former would also result in a non-competitive market and the latter would imply an optimal scale of no output.

It is obvious that the only possibility consistent with competition is that increases in scale of operation cause an initial decline in unit costs, followed by a rise. A further condition for competition is that the same cost pattern should apply to management and administration, to prevent the control of several least cost production units by one or a few owners. It is for this reason that neoclassicals use the word “firm”, which refers to the “decision unit”. It is difficult to justify why such a unique minimum unit cost point should be the general case, other than pursuing some variation of Adam Smith’s famous cliché that the owner (“master”) of an enterprise cannot watch everything all the time.

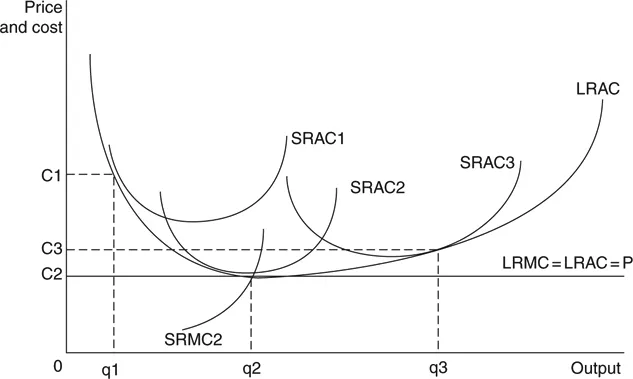

It would appear that Jacob Viner was the first to formally specify the necessary conditions for a unique minimum cost (Viner 1931), and this is shown in Figure 1.1. The lines identified as SRAC are short run average costs curves. These derive from a production function in which the capital stock is fixed, the amount of labor varies, and there are no other inputs. Therefore, total cost equals wages plus interests. Neoclassical firms do not produce products, they generate a flow of homogeneous value added, an analytical simplification ridiculed by Keynes (Weeks 1988).4

Figure 1.1 Perfect competition and how to get there: “U-shaped” long run average cost.

Assume that initially the firm operates with cost curve SRAC1, implied by some fixed capital stock k1. Were the “deciders” to expand the scale of operations, the unit costs would decline until they reach a minimum at unit cost C2 and output q2. There are scales of operation smaller and larger that could produce the same output, but the unit cost would be higher. Should the deciders optimistically construct operations corresponding to SRAC3 in hopes of seizing a large market share, they would discover to their grief that smaller scales of operation had lower unit costs. All firms converge on the scale of operations corresponding to SRAC2.

The long run average cost curve, LRAC, is the locus of the point on each short run curve that is the lowest unit cost for each level of output. This lowest unit cost for each output is not the lowest unit cost on each short run curve, except for SRMC2. Legend has it that this characteristic of the cost curves left Viner perplexed. The long run curve is badly named, because it does not refer to chronological time. It is more accurately called a “planning curve”, which allegedly shows the alternatives open to the deciders as they reflect on future investments. In the rather strange future that they reflect upon there is no technical change to disrupt the shape of the long run average cost curve.

This is a story so analytically flawed that is astonishing that it was taken seriously when Viner proposed it, and amazing that it is being repeated eighty years later. The first problem with Figure 1.1 is that it reflects an analytical process that in sailing is called taking “back-bearings”, determining where one is by inspecting from where one must have come. The “U-shaped” average cost curve, short and long run, is the same. The story in Figure 1.1 would have some credibility if through theoretical analysis it were established that production functions would produce as a general case U-shaped short and long run average cost curves. The reverse was the case: faced with the pressing need for a cost structure consistent with many firms, Figure 1.1 was conjured up with no basis in a mathematical function.5 This is one of many examples of neoclassicals hoping that nature will imitate art. Another example, “false trading” is considered in the discussion of competition under general equilibrium.

Second, no empirical evidence has been produced to support the argument that U-shaped average cost curves are the general case. This is not surprising, because the theory on which it is based is weak to the point of non-existent. It is a reasonable hypothesis that production facilities cannot grow larger and larger without limit before encountering problems that would limit efficiency. There is little reason to believe this is a binding constraint across all sectors. More basic, there is no reason to think that ownership of many production facilities would encounter systematic inefficiencies. Were this generally the case across sectors, it would be difficult to account for the prevalence of multinational enterprises.

Third, the analysis behind Figure 1.1 excludes technical change. This alone renders it non-credible. One is asked to believe that competition results from a process in which the owners of capital consider different scales of operation and choose among them, without assessing the impact of technical change on the possible choices. The exclusion of technical change from the analysis is not accidental. Were it included, outcomes would be indeterminate, carried to a far more complex level of asymmetric information and uncertainty.

However, were all other objections to Figure 1.1 ignored, one would remain that undermines the analysis. It represents the inappropriate application of partial equilibrium to a general equilibrium phenomenon. The choices by the owners of firms manifested in Figure 1.1 are based on notional quantities and prices. Notional values are those that result when all markets clear. In other words, they are a general equilibrium concept, but the diagram is partial equilibrium with no explanation of how prices of outputs or input are determined. Without an explanation of this process, Figure 1.1 is irrelevant because the participants in the market receive no price signals. In the absence of price signals, owners of firms set prices themselves; this is the negation of perfect competition.

Competition in general equilibrium

The standard definition of competition from textbooks – many buyers and sellers, homogeneous product, etc. – is a low and vulgar theory. The neoclassical high theory of competition is found in Walrasian general equilibrium analysis. The superficially simple idea that many buyers and sellers interact to create competitive prices has no analytical content outside of the context of general equilibrium. Petroleum is a clear a...