![]()

PART 1.

INSTRUCTIONS

Collective Learning for Transformational Change

![]()

1 The theory: Collective social learning

Summary:This chapter begins by exploring social learning. It then discusses David Kolb’s work on individual experiential learning. His ideas are extended into a collective social learning capable of guiding transformational change.

Note: This chapter is for those who wish to know the theory behind the practice. For readers with a greater interest in the practical aspects, rather than the theory, go straight to Chapter 2. Here you’ll find a template for guiding transformational change. You can then choose from the 16 case studies in Part 2. Read those along with the template to guide your collective learning process.

About social learning

Social learning is part of our everyday life. It is the pathway through which we learn to live in a shared world, a world that will inevitably be different from that of our parents and different again for our children. This is an era of continuous rapid social and environmental change. Apparently simple changes in social behaviours, such as an increase in everyday use of childcare centres, or the ready take-up of mobile phones, are but symptoms of core changes in work patterns and family units, which in turn change our interaction with both our social and our physical environments.

Personally and professionally, we are all by definition involved in social learning. It has made us who we are, and allows us to fit into the society in which we were reared. Social learning inevitably goes beyond that of each individual to shape the whole of society. The effectiveness of a society’s capacity to change is marked by the willingness of the members of the society to go beyond their traditional social practices. Transformational social change involves questioning existing rules and boundaries, and finding new solutions and ways of living. However, rather than being welcomed, change can be strongly resisted. The pull of the traditional ways of defining individual goals, professional practices, and organizational cultures can be stronger than the push of the need to change. Yet changes in all of these are needed if there is to be a transformational change (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 Seven Ages of Man

In the sixteenth century Shakespeare described seven ages of ‘man’: infant, schoolboy, lover, soldier, judge, aging, second childhood. At that time the use of the word ‘man’ was accurate since the ages applied only to the males of his society, when only boys went to school or became citizens. Today a social transformation has meant each of the transformational ages applies to both sexes.

Every society has traditions that mark each of the seven age transformations by collective social learning. For instance, in 21st century Western society coming-of-age from child to adult is marked by physiological changes, voting, driving, drinking, and earning. Each of these actions involves the society’s structural supports: politics, law, health, science and economics. There is no such thing as an entirely free individual; we are all created by our society. Even a protester recognizes the social rules – they just want to change them.

Social learning can therefore be a mixed blessing. On the one hand it is the glue that holds society together, a cultural inheritance that is passed down through the generations, and the security of knowing that things will go on as they always have. On the other hand traditional social learning can act as a brake on change, since it is more concerned with maintaining the old than introducing the new. The interaction between the traditionalists and the innovators is therefore a significant tension. In times of transformational change the tension can escalate into outright conflict. Hence the political unrest sweeping around the planet, and the impasse between responses to climate change, well-documented in Les Brown’s ‘Vital Signs: the trends that are shaping our future’.

With constant transformational change becoming a distinctive feature of our time, some conflict is inevitable. The pressures for change manifest themselves in many ways. The impact of human activities on the planet is so great that changes are necessary for a viable human future. Financial crises follow one another with no end in sight. Advances in technology appear to offer the answers, and then the answers cause further disruption. Communities need to support their members through the rapid pace of social change. Scientists, politicians, industry leaders and communities each offer solutions, but they are competing solutions. The question is, how can we move forward to welcome change within this chaos?

A first step is to recognize the need for a social learning that celebrates rather than impedes change – a redirected social learning. A second step is to recognize that major change necessarily generates complex social issues. These complex issues require a quite different approach to that of addressing the simple problems of maintaining business as usual. The American wit, Mencken, writes ‘For every complex problem there is a solution which is simple, clean and wrong’.

A simple problem can be solved through applying the simple logic of cause and effect; a complex problem asks for a far more comprehensive understanding of the issues.

For instance, a troubled community may need improved social services, or it may need to develop new mutual support systems to cope with change. Halting environmental degradation may mean protecting a threatened species, or it may mean developing a comprehensive environmental management system involving all parties. If new technology is to provide more than a stop-gap solution, it will require complementary changes throughout a society. In each of these examples, the second more comprehensive change will require mutual learning and understanding across all the sectors of the society.

The capacity for mutual learning among all the interests in a society may well be the key to successful transformational change. It is not so easy to achieve, however, in a society with strong divisions between ways of thinking about the world. The divisions between ages, gender, beliefs and values, places, and income levels build strong walls of thought and language which serve to strongly reinforce the existing system. To bring change to one is to threaten the continuity of the others. The entry of women into the workforce, increasing economic inequality and an extended life expectancy are but a few of the changes affecting Western social systems. Learning is needed to bring windows into those walls, so that changes can be judged on their full effect on the whole of society.

Box 1.2 A Matter of Time and Place

What constitutes politics, law, health, science and economics is a matter of time and place. To the ancient Greeks achieving democracy meant individual citizens speaking in the market place, in our era a formal process involving over a billion people globally every three or four years. The delivery of nineteenth-century law was punitive in the extreme, now there is an emphasis on potential rehabilitation. Health is very much a matter of time and place: life expectancy in Europe rose from forty to eighty years in a century, sharply altering the expectations of Shakespeare’s ages.

Transformational changes are therefore part of the human condition. A major difference between then and now is a rising confidence in the human capacity for deliberate human-directed transformational change. In past times, transformations have been regarded as the business of the gods, of authoritative figures, and of chance. There has been a twentieth-century social transformation from accepting the world as it is, to the belief that humans could intentionally reconstruct their own world. Dramatic changes in the planetary environment resulting from human activities, such as the increase in the ozone hole and rise in mean temperatures, have confirmed this belief. The practice of social learning has been extended to guided transformational change.

David Kolb and experiential learning

Since all learning starts in the individual human head, individual learning is a good place to start before considering social learning as a group exercise. A seminal writer on individual adult learning, David Kolb, offers a blueprint for individual learning that can be used across a whole society to guide harmonious transformational change. Building on the work of other influential educators, the Kolb learning cycle draws on Jean Piaget’s stages of intellectual development, Paulo Freire’s emphasis on the need for learning through conscious reflection, Kurt Lewin’s insights into organizational cultures and Carl Jung’s assertion that learning styles result from people’s preferred ways of adapting in the world.

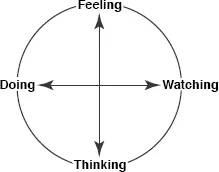

Kolb put forward the proposition that all individual learning is based in the learner’s reflection on direct experience. His approach is therefore called experiential learning. In its simplest form experiential learning is a matter of completing a cycle, first feeling that something is important, then watching what is actually happening, thinking about the possible consequences and acting on those thoughts (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The key elements of experiential learning

David Kolb expressed these four forms of experience as concrete experience, observation and reflection, forming abstract concepts and testing them in new situations. He represented these in the famous experiential learning circle in a sequence that involves, for any one issue,

1. Feeling: ideals developed from past experience, followed by

2. Watching: facts determined by observations, followed by

3. Thinking: new ideas generated by using the imagination, followed by

4. Doing: actions that test the new ideas in the old situation (Figure 1.2).

The changed situations offer new experiences that challenge previous values and so the cycle becomes a spiral. Kolb and his colleagues found that the same cycle appears time and again as the basis for any substantial and lasting learning.

Two aspects of the learning spiral are especially noteworthy: the use of concrete, ‘here-and-now’ experience to test new ideas; and the use of feedback from different aspects of experience to change existing practices and theories (Kolb 1984: 21–22). Kolb named his model experiential learning to emphasize the link with the work of John Dewey, Paulo Freire and Jean Piaget, all of whom stress the role direct experience plays in learning.

Observations of the learning cycle made by many researchers across a wide range of situations confirmed that the learning cycle could be generalized to all significant adult learning. The observations also confirmed that different interests gave a different emphasis on different parts of the learning cycle.

In our divided social system, standard social learning has ensured that learners tend to have already developed a strength in, or orientation to, one dimension of the learning cycle. Scientists choose to prioritize observation, planners depend on their capacity to think strategically, caring services draw on an ability to feel compassion and practical occupations learn by doing. These differences are explored in Chapter 10 on guiding transformational change.

After decades of studies in the field, researchers found that there were some consistent learning styles associated with certa...