![]()

Part One

Development

![]()

1 The Political Economy of the Allende Regime

This essay was originally published in P. O’Brien (ed.), Allende’s Chile (New York: Praeger, 1976), pp. 51–78, and was written in the immediate aftermath of the military coup, that is, at the end of 1973.

I taught in the planning institute of the Universidad Catolica de Chile in September-November 1972, and revisited the country in March 1973. I tried to the best of my ability to understand what was happening, what the policy of the government was, and the causes of the economic troubles that were besetting it. What follows is an attempt to analyse the economic policies that, beyond doubt, contributed to the disaster that befell the Allende regime. It may be of interest to note that when I expressed many of the same ideas in Santiago in November 1972 I was criticized by most of those who heard me for a harsh and unsympathetic approach. I denied then, and I deny now, any harshness or lack of sympathy. The facts point to a lack of clarity and a great deal of contradiction and confusion, due partly to divided counsels, partly to political constraints and partly to a fundamental dichotomy in the economic-political strategy of the administration. of course, defeat was due also to the actions of the government’s enemies, but grave errors gave these enemies far too many opportunities to exploit. To pretend that the government merely fell victim to a conspiracy between the CIA and the extreme right is of no help to anyone, least of all the Chilean left – which is not to deny the obvious facts of conspiracy and sabotage. In any conflict in which one is defeated, it is self-evident that the enemy’s actions made a major contribution to the outcome (and deserve more careful study than they will get in this essay). However, in any inquest on a lost battle attention is usually and rightly devoted to analysing one’s own errors, and to discovering why one was not successful and the enemy was. The conspiracy-based explanation leads logically to far-reaching conclusions about the impossibility of a peaceful road to socialism. In one such version the onward march towards a just society was violently interrupted because it was in fact succeeding, whereas (in my view) by early 1973, indeed, by the second half of 1972, catastrophe faced the economy, with the gravest political consequences plainly discernible. It may indeed be true that there is no ‘peaceful road’ in Latin America (or Italy, or anywhere), but the case for this proposition should not rest on myths about Chile.

One first must take cognizance of the class structure of Chile. It is a country with a very large class of small shopkeepers, owners of workshops, artisans, owner-drivers of trucks, small peasantry, and other members of what must be called the petty bourgeoisie. There was, of course, a group of big businessmen, many of them linked with foreign corporations, and an upper stratum of senior civil servants, officers and professional people; the officers were (by Latin American standards) rather poorly paid, but took great pride in their disciplined nationalism, as could be seen each Independence day in their spectacularly precise goose-stepping. The tactic appropriate to a left-wing president was, it seemed, to attract or at least neutralize the petty bourgeoisie, while gaining peasant support by pressing ahead with land reform, which had been begun slowly under the previous president, Eduardo Frei. Allende, understandably, sought to reassure the petty bourgeoisie and promised to take action only against the foreign corporations and the few Chilean big monopolists. It was surely essential for the security of the regime not to antagonize the ‘small men’.

I appreciate that constraints and limitations are not unchangeable, and that observers can and do differ in interpreting the limits of the possible. But it is sufficient here to stress that economic policies were conceived and carried out within a social and political structure that set limits to what Allende and most of his colleagues considered it possible to do.

The Economic Legacy of the Frei Administration

Chile, when I first visited it in 1965, was facing economic difficulties. First, there was the chronic inflation, which had gone on for many decades. The behaviour of the price index in the years of Frei’s presidency is shown in Table 1.1. Food supplies were adequate only because of substantial imports, and this for a country that, a generation earlier, had been a significant exporter of grain and meat. Agriculture had for too long been in the doldrums, and this was attributed by most Chilean economists at least in part to the inefficiency or inactivity of the landed proprietors, whose liking for horse-riding in ponchos – and holding land as a hedge against inflation – exceeded their interest in productive activity. Frei’s Christian Democrat administration did indeed adopt land reform laws, and we shall see that Allende’s speeded-up land reforms were based on these very same laws.

Table 1.1 Price rises (per cent)

| Retail prices | Wholesale prices |

1967 | 18.1 | 19.3 |

1968 | 26.6 | 30.5 |

1969 | 30.7 | 36.5 |

1970 | 32.5 | 36.1 |

Source: Antecedentes sobre el desarollo chileno (Santiago: ODEPLAN 1971).

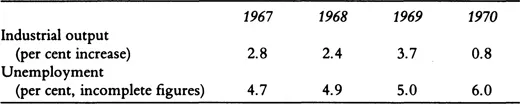

Industrial output rose only slowly, or stagnated. Chile is not a populous country, and the industries that operated under cover of a high tariff wall were unable to benefit from economies of scale. A foolish policy of indiscriminate encouragement to foreign capital led to setting up more than twenty small car assembly plants, all far below optimum size. Unemployment grew, and there was much under-utilization of industrial capacity. The 1971 ODEPLAN figures (Table 1.2) give one some idea of the trend. Thus in the last three Frei years inflation rates rose, industrial output showed little upward trend and unemployment increased.

Table 1.2 Industrial Output and Unemployment, 1967–70

Source: Antecedentes, op. cit.

The balance of payments was a constant source of concern. With nitrates no longer significant, and an increasing food import bill to meet, Chile’s exports consisted largely of copper, which accounted for around 80 per cent of the total. The country was thus very vulnerable to price changes of this one commodity, import-saving’ industrialization led to increasing imports of machinery and components, and the bulk of Chile’s oil also had to be imported. In addition, Chile had to carry a large burden of debt, both governmental and commercial. Frei succeeded in coping with the balance of payments, building up reserves in the process (see Table 1.3). However, this increase in reserves was achieved by damping down activity, and this contributed to unemployment of human and material resources.

Table 1.3 Balance of payments (US

)

| Net balance | Reserves |

1967 | –25.0 | –91.5 |

1968 | +127.0 | 37.7 |

1969 | +222.8 | 220.0 |

1970 | +108.2 | 343.2 |

Source: Antecedentes, op. cit., pp. 435–6.

The copper mines were, in the main, US-run, by the Anaconda and Kennecott companies. Frei decided to ‘Chilanize’ them, acquiring a 51 per cent controlling shareholding. However, the terms of the agreement proved highly favourable to the copper companies, who made and remitted unusually high profits in the years following ‘Chileanization’.

Allende’s Economic Programme

Allende’s victory was unexpected, and there is some evidence that he was caught unprepared, with no defined plan of action. His programme promised to contain inflation, to redistribute income in favour of the poor, to carry out a rapid land reform, and to nationalize the copper companies, other foreign-owned corporations and big monopolies. Thereby it was hoped to weaken the economic-political basis of the right-wing parties, to strengthen the electoral popularity of the regime and to move onwards towards socialism. These onward moves were by no means clear. Nor were the ways in which the various elements of the immediate programme were to be carried out. There was, we may be sure, much improvisation.

Two factors must be stressed. The first was that the election of Allende touched off great expectations among the working-class supporters of Popular Unity (UP). Life would become better, wages would go up, they would soak the rich. The strength of these expectations, as well as the government’s own commitment to income redistribution, made it politically essential to grant large wage increases, while simultaneously combating inflation. The other factor was disunity, or rather divisions, on the left. The trade unions were united under CUT (Confederacion Unica de Trabajadores), but within them the parties competed, with the Christian Democrats vying with the Communists, who controlled CUT, in promising or demanding immediate benefits. Politically, too, there were those who urged massive concessions to the workers, to win their enthusiastic support as a first and essential step towards mobilizing them for the march towards socialism. Some of Allende’s supporters thought of the possibility of a plebiscite to amend the Constitution to give the government greater powers, and large benefits for the masses could mean votes. Some of the parties in the UP coalition, especially the socialists under their secretary Altamirano and two of the smaller parties (MAPU and the Left-Christians), were for a vigorous socialist offensive and for extensive redistributive measures in favour of the poor. Allende himself seems to have been nearer the Communists in urging caution. It was, above all, the Communists who sought to reassure the middle classes, insisting that legality should be respected and attention paid to economic possibilities. They were outflanked from the left not only by the MIRistas, who were urging seizures of property and challenging the very concept of legality, but by the other members of the coalition. (I recall the mocking tones of Chilean postgraduates whom I met at an international seminar in the summer of 1971; the Communists were a bourgeois party, they insisted.)

The government knew that it could nationalize copper with the overwhelming support of the people and of Congress. It promptly did so, virtually denying compensation by claiming that excess profits and unpaid taxes in the past should be deducted from the compensation entitlements of Kennecott and Anaconda. Whether it was wise to do this is a matter of opinion, for the government risked more trouble with the United States as well as with the firms in question; the latter were important as suppliers of equipment to the mines, the former could (and did) take steps to cut Chile off from credits which, possibly, might have helped to mitigate the balance-of-payments problem. It is worth inquiring whether the failure to compensate caused, on balance, more loss than gain. Chilean delegates could have dragged out compensation negotiations for years, while accepting the principle, thus weakening the argument of the government’s enemies, who (as the ITT files show) were hard at work persuading American official agencies to take hostile action. (It is, of course, also arguable that the United States would in any case have done its worst, whatever the compensation paid for copper.) Could it be that the fine ‘declaratory’ value of the no-compensation principle was a luxury that Chile could not afford? Whether one accepts this view or not, there is no doubt at all that the action was popular. Even the right-wing deputies in Congress voted for it.

The nationalization of other enterprises was more difficult. A list of ninety firms was drawn up and submitted to Congress, which turned it down. There was thus no direct legal road, and so the government was forced to resort to a number of expedients. These included participation on a 51 per cent basis in the case of foreign-owned enterprises, a procedure that covered, among other things, some enterprises owned by ITT (such as the Sheraton hotel). Participation could be achieved by direct negotiation with the enterprises concerned, in the knowledge that their foreign ownership would give the government political strength in dealing with them. If the enterprises refused – as I was told Philips refused – they were sometimes allowed to carry on, because of the loss that would follow from their withdrawal. Chilean-owned big firms would be, and were, tackled on the basis of existing legislation or by indirect forms of executive ingenuity, as follows.

(1) The government acquired control by purchasing controlling shares. For example, this was how banks were acquired, and some industrial firms also. The process was in some cases facilitated by related actions; demands for large wage increases, price control and denial of import licences could, separately or in combination, cause sufficient losses to ‘persuade’ the directors to sell.

(2) Use was made of legislation adopted in 1932 under the short-lived rule of a left-wing president, Davila, and never repealed. This provided for control over (not nationalization of) enterprises that were not being operated in a vaguely defined public interest. The government put in an interventor, who replaced the board of directors. By this means, state control was much expanded. Again, the incomes of owners could be reduced by a combination of price control and wage increases.

(3) Finally there was action from below, often encouraged by one or more of the UP parties but sometimes spontaneous (or MIR-inspired), in which workers occupied factories and/or demanded that the government take over control from the owners.

By these and similar means the so-called area social (Social Property Area), that is, the state-controlled sector, was substantially expanded by stages. But these methods caused not only bitterness but also confusion and uncertainty – bitterness because they were seen as a way of evading legislative opposition to nationalization, confusion because ...