![]()

Chapter 1

The Demographic Framework

AN ‘OPTIMUM’ POPULATION SIZE

As many people may have to be accommodated in Britain in the final third of this century as have been accommodated in the first two-thirds. To some this constitutes a nightmare, but the great majority of official witnesses who gave evidence to the Select Committee on the consequences of population growth [1] took a complacent view. The then Secretary of State for Local Government and Regional Planning (Mr Anthony Crosland) voiced a common opinion: ‘I have not as yet heard any argument in terms of pressure on land which leads me to the view that any government at the moment should have an active population policy. . . proper and effective planning [can] cope with the increased demand for space without any decline in the quality of life.’ A minority, however, like the Conservation Society, [2] expressed serious concern about the increasing pressures upon the limited land of Britain, and argued that ‘additional numbers can only diminish the quality of life’. The Select Committee echoed the mounting public concern—of which its report was symptomatic— and recommended the establishment, as an integral and permanent part of the machinery of government, of a Special Office directly responsible to the Prime Minister, which would study, appraise, publicize and advise upon the implications of population trends. Unfortunately, the report coincided with a major move (introduced by the Conservative Government which was returned to power in June 1970) to bring about ‘less government, and better government, carried out by fewer people’. [3] The time was, therefore, hardly propitious for the setting up of a new piece of governmental machinery, particularly in such a politically delicate field. Nevertheless, it was decided to appoint a ‘small mixed panel of experts’ to assess the available evidence about the significance of population trends and to identify the gaps in knowledge. [4]

For a complex of reasons, including the impossibility of predicting the future and the difficulty of achieving consensus on the elements which make up ‘the quality of life’, government has traditionally steered clear of ‘population policy’. This is in spite of the fact that a Royal Commission on Population, which was set up in 1944 (following the large fall in births in the thirties), stressed that ‘it is impossible for policy, in its effects as distinct from its intentions, to be “neutral” on this matter since over a wide range of affairs policy and administration have a continuous influence on the trend of family size’.[5] However, the problem arises in establishing direct causal relationships and in judging what an ‘optimum’ population size would be. Even if agreement could be reached on this, it would, in the words of the then Secretary of State for Social Services (Mr R. H. Crossman), ‘be a terrifying prospect to know what one would do about it’. This is a field in which politicians have shown an untypical modesty. The power of government to influence events is frequently much less than they would have us believe: it is unusual to find them claiming, almost unanimously, that a crucial issue is beyond their powers, even though other countries have made the attempt with signally little effect.

There is no doubt that the issue is extraordinarily complex, but then so is economic policy—and who in the 1930s would have dreamt of an all-party commitment to full employment? The truth of the matter is that population policies would necessarily be very longterm both in their aims and their effects, and that short-lived governments are unlikely to attempt to influence such distant events unless they are compelled to do so by public opinion. There are signs that this may come. Though, as the experts stress, it may be impossible to determine the ‘optimum’ size of the population, public opinion may come to view the prospect of a major increase with such apprehension that government will be forced to act.

The scope for action and its likely effectiveness or otherwise cannot be explored here. [6] Our predominant concern is with the distribution of population over the country and the social and economic implications of its structure and its activities. Nevertheless, the starting point must be the size and growth of the population. The discussion will incidentally demonstrate some of the difficulties which would face the framers of a population policy.

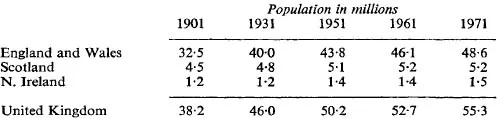

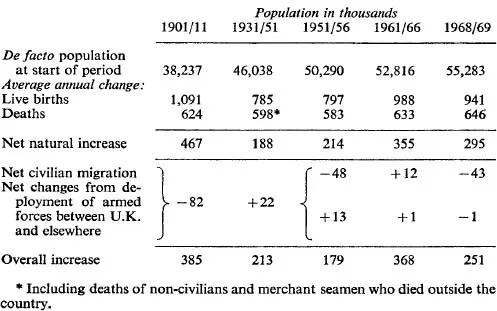

TWENTIETH CENTURY POPULATION TRENDS

The population of the United Kingdom increased by 17 million between 1901 and 1971: from 38·2 million to 55·3 million. The major reason for this increase has been the excess of births over deaths, but outward migration reduced the total increase by some 2 million. The 1930s were exceptional in that there was a gain in population due to migration (averaging 90,000 a year): this was due to the influx of European refugees and the fall in the number of British emigrants to the old Commonwealth in the economic depression of this period. The late fifties and early sixties were similarly exceptional: in this case because of immigration from the New Commonwealth. This was severely cut back by the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act: since then there has been a net outflow of population.

The excess of births over deaths—the ‘natural increase’—was at its highest in the first decade of the century, but the number of births declined greatly in the period up to the second war: from an annual average of 1,091,000 in 1910-11 to 720,000 in 1931-41. This gave rise to considerable anxiety, since though the population was still increasing, the number of births was insufficient to replace the generation to which their parents belonged. Had fertility remained at the low level of the thirties, the population would have declined in the long run. Indeed, there was speculation that the population might decline to 10 millions within a century.

A Royal Commission on Population set up in 1944 deliberated for five years and provided a sober assessment of the position, and concluded that total numbers would continue to grow, ‘perhaps for another generation’, but the growth would be neither rapid nor large. Future births would ‘almost certainly’ decline in the following fifteen years, but the more distant future could not be readily forecast. Nevertheless, if average family size remained constant, total numbers would reach a maximum around 1977 and would, thereafter, begin a slow decline. A small increase in family size would lead to a stabilization of the population—which the Commission thought to be eminently desirable. Though it was possible to hold widely different views about the optimum size of the population in relation to national resources, ‘if over a long period parents have families too small to replace themselves, the community must undergo a slow process of weakening’.

It needs to be remembered that it was in this context that postwar planning was conceived. No one anticipated the very large and sustained growth which actually took place.

The nature of this change can be quickly outlined. Following the end of the war, an expected ‘baby-boom’ took place (as it did after the first war) and births rose rapidly to a peak of 1,025,000 in 1947. Thereafter, the number of births began to fall and the evidence appeared to point overwhelmingly to a reassertion of the low fertility pattern of the thirties. But the fall was arrested: in the mid fifties births averaged 800,000; by 1960 they topped 900,000; and in 1964 reached 1,015,000. (Since then they have fallen steadily, reaching 903,000 in 1970.) The Royal Commission had thought that 54 million was the highest likely figure for the population of the U.K. by the end of the century: this number was surpassed in 1966.

It is, however, one matter to present the figures: it is quite another matter to attempt an explanation. It is now widely believed that the prolonged economic depression of the thirties exerted a significant influence on the birth rate even though the currently used techniques of birth control were relatively inefficient. On this interpretation, post-war prosperity is a major factor. In fact, there are many threads here which are difficult if not impossible to untangle. During the inter-war years the sex-ratio at the normal marrying ages was considerably affected by the male slaughter which took place in the 1914-18 war: enforced spinsterhood was more than a newspaper story. Social attitudes have changed radically. [7] In ‘the permissive society’, the interval between meeting and marrying has shortened (and, lest this should be thought to be confined to the young, it needs to be pointed out that the interval has become proportionately even shorter for older women). Further, two-fifths of the first births to brides under the age of twenty at marriage are extra-maritally conceived (the proportion for the oldest brides—those whose age at marriage is forty or more—is also at the high rate of nearly 28 per cent).

Table 1 Population of the United Kingdom, 1901–1971 [8]

Whatever the underlying forces, the demographic features are clear. There has been a major increase in the popularity of marriage: more now marry and the age of marriage has fallen. In 1931, 26 per cent of women aged 20–24 had married, but in 1961 the proportion had risen to 57 per cent. The proportion ever-married in the age group 40–44 rose from 81 per cent in 1931 to 90 per cent in 1961. (It has since risen to 92 per cent.) The average age of women at first marriage was 25·7 in 1951 but 23·2 in 1961 (and 22·7in 1968). Furthermore, though it is still a matter for conjecture, it is possible that the average number of live-born children to those marrying in the late fifties and early sixties will be nearly 2·5. (Currently, to achieve replacement the figure would need to be around 2·1.) This apparent trend does not signal a return to large families: it is explained by a substantial reduction in childlessness and by a shift from the one-child family to families of two or three children.

Table 2 Elements of Population Change, Selected Periods [9]

The moralist will also point to the increase in illegitimacy, from between 4...