![]()

1 A perspective on conflict and peace1

Johan Galtung

Dilemmas of conflict and peace

In 1967, in a project for the Council of Europe, a theory was developed for positive peace, inspired by what at that time was the European Economic Community (EEC), the Nordic Community, the beginnings of what became the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Panchsheel2 between China and India, and above all by Switzerland. The aim of the project was to resolve under what conditions different states, and nations within states, could not only handle conflicts without violence-negative peace, but engage in cooperative projects for mutual benefit-positive peace. Diplomacy was needed; as an institution, diplomacy had evolved from ad hoc envoys via resident bilateral diplomacy and multilateral ad hoc conferences to multilateral permanent organisations, with the United Nations (UN) as the crowning achievement so far. Conflict theory points to multilateralism rather than bilateralism, since a two-party situation has a built-in polarisation less open to deals that can lead to resolution.

Five necessary conditions have been identified for positive peace (Galtung and Lodgaard 1970):

1.symbiosis — mutual benefit;

2.equity — equal benefit;

3.homology – same structure, ‘opposite numbers’ easily identified;

4.entropy — cooperation mass well distributed between:

- government with government

- government with non-government

- within one state

- between states

- non-government with non-government;

5.transcendence — something more than the sum of states or nations, in practice a multilateral organisation-secretariat.

Diplomacy had been at that stage since the League of Nations, but the states were so different that the conditions of homology and entropy were not satisfied. According to this theory, much more was expected from the six-party multilateral Treaty of Rome EEC of January 1958 than from the German-French bilateralism of May 1950, which centred on two issues: coal and steel. The rest is history, both as broadening of the domain from six to 27 members, and as deepening of the scope from two to diverse cooperation items today. The European Union (EU) story is a success both from a negative and positive peace point of view, capable of handling a rolling agenda of issues, but with such glaring exceptions as the democracy deficit and the euro zone crisis, among other things.

The project for Council of Europe went beyond the Western European countries to the area spanned by NATO–Warsaw Pact–neutral non-aligned (NN) countries. Research was carried out in 19 of those countries, from Washington, DC to Moscow, from Norway to Greece. The most critical conflicts were, of course, over borders, human rights, arms races and deployment, particularly of nuclear arms; the most promising project was economic cooperation under the institutional umbrella of the UN Economic Commission for Europe in Geneva. By simple extrapolation, a UN Security Commission for Europe was among the proposals, with links to what became the Conference-Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (C(O)SCE) in Helsinki/Vienna.

During the Cold War (1949–1989) four conditions were identified for a more modest goal — survival of a hot war (Gaining 1984):

- being neutral non-aligned — not being a member of military alliances;

- using defensive defence as the military doctrine;

- self-reliance, so not going to war for resources;

- usefulness to others if kept intact.

This singled out Switzerland, Albania and Yugoslavia, and then Finland, Sweden and Austria as the most likely survivors. More geared towards negative peace, we can only celebrate that the theory was not tested.

In 2010, 20 years away from the Cold War, and the perspective is no longer North Atlantic and Europe-centred, but the era of globalisation. The Warsaw Pact has been dissolved and NATO has expanded eastward, breaking the promises to Gorbachev. The Soviet empire has collapsed, along with communism. In the view of the author the US hegemony is also collapsing (Galtung 2010), and the brand of capitalism it stands for is in deep crisis. These deep and very quick processes — forgetting the accelerating effect of living globally in real time, with ultra-quick communication — lead to a number of key questions, including some about the status and influence of the EU.

On its long march from community-confederation to federation-superstate, the EU has for a long time been ‘a superpower in the making’(Galtung 1973). The joint foreign policy and joint security policy of a federation are lagging, but probably emerging; the euro zone with 17 of the 27 goes far towards a joint financial policy, the present problems notwithstanding. How far the system has moved towards a joint army, joint arms production, joint command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I) and access to nuclear arms of member states is difficult to judge. There is a joint passport, an anthem, a day of celebration. But is there really a joint enemy? The situation is ambiguous. The capability, like for a rapid deployment force (RDF) with a global reach is approaching that of other superpowers, be they fallen or falling. With 11 former colonial powers there is much tradition to be re-enacted, and a ‘joint foreign policy’ of the ‘I'll accept your activity in your former area if you accept mine in mine’ variety is needed. But what is the intention? Is it for security for the Council of Ministers and peace for the Commission, or both for both, but with different weighting, military for one, civilian for the other? Or is it towards filling a possible gap when the US hegemony falls and China is unwilling to or incapable of doing so?

We live in a context of two major and related processes. First is regionalisation, based on high-speed transportation and communication, which comes up against cultural borders. Four regions exist — the EU; the African Union (AU); the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC); and the ASEAN — and four are yet to come — Estados Unidos de America Latina y el Caribe (ALC); a Russian Union (RU), with autonomy for all non-Russians; an East Asian community like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), with 50 per cent of humanity; and the Organization of Islamic Community (OIC), the ummah from Morocco to Mindanao. Second, the rapid decline and fall of the United States, which, if handled well, may be a blessing for the US Republic as it was for the 11 EU member colonial countries liberated from empires.

The successor system to the present state system with a hegemon will not be a state system with China or the EU as hegemon; nor will it be a globalisation with that much cultural diversity. Quick transportation and real-time communication transcend state borders, but because cultural vicinities and affinities prevent globalisation with a single state — The World — and one nation — humanity — these will not emerge onto the scene until later. We have to make do with waxing regionalisation between the fading state system and a future globalisation. The successor to the present system will be regionalisation, and the EU – being the most mature region — will/can play a major role. There are four regions containing more than 90 of the 192 UN member states: the EU (27 states); the AU (53 states); the SAARC (eight states); and the ASEAN (ten states). Further, three areas seem likely to undergo regionalisation processes: the SCO (six members), Latin America (LA) and the Caribbean (35 countries) and the OIC (as a deepening of the present Organization of Islamic Conference, with 56 members from Morocco to Mindanao; also seen as a struggle for a new caliphate). Russia may one day become region number 8 (the RU), granting Chechnya as much autonomy as the Netherlands has inside the EU. Of the eight regions, the EU, LA, OIC, SAARC and Russia are mono-civilisational, with huge minorities, and AU, ASEAN and SCO are multi-civilisational, more typical of a globalised world.

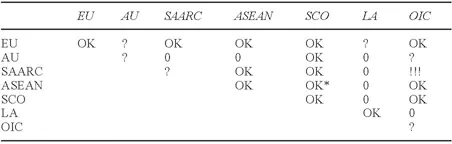

Some countries are not clearly included in these eight regions: the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and Japan. Will they one day form their own region? Or will younger people in the UK prefer the EU, in Japan the SCO, in Israel some Middle East community, in Australia (with New Zealand) also the SCO, leaving the United States with MEXUSCAN,3 with Mexico as a bridge to Latin America? From the history of an interventionist United States it follows that a successor system is neither peaceful nor the opposite. What follows? Let us project the seven most likely regions with seven relations within, and 21 bilateral relations between them — altogether 28 — into a future where there will still be states and nations around, but losing in salience to regions and civilisations (Table 1.1).

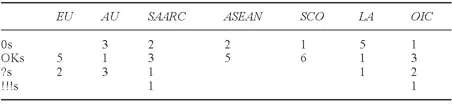

The regional, multilateral world shown in Table 1.1, with seven ‘no relation’, 14 ‘okay relations’, six ‘problematic relations’(EU penetrating AU and LA, and intra-regional problems), and only one ‘gross problematic relation’(SAARC-OIC) actually does not look that bad at all (Table 1.2).

The most isolated region is LA. The region relating best to all the others is the SCO, closely followed by the ASEAN and EU. The region with most problems with others is the AU (lack of stability within, structural violence from the EU and direct violence from the OIC). The worst problem is between the SAARC and OIC. Looking at the list of the three postulated coming regions, the SCO, Latin America–Caribbean and the OIC are on the way, provoking US counter-forces. An East Asian Community with the two Chinas, the two Koreas and the two Japans (with the Northern Territories) is also taking shape, without Russia and four of the Central Asian republics. The SCO is a reaction to the United States encircling the Russia–China land mass, and may disappear with that encircling, paving the way for East Asia.

Table 1.1 Probable inter-regional relations

Notes

In Table 1.1 ‘0’ means no relation, ‘OK’ means exactly that, ‘?’ means that there are problems and ‘!!!’ means gross problems.

*The ASEAN initiative to establish an ASEAN+3 (China, Japan and South Korea), an East Asian Economic Community like the Asia Pacific Economic Community, the United States–Pacific rim, paralleling US Atlanticism with Europe, may coexist with those highlighted here because they are more cohesive, less artificial. But the intra-bloc trade ratio is impressive for ASEAN+3 (60 per cent), even if beaten by the EU (70 per cent).

Table 1.2 Regional relations profiles

What would be the status and influence of the EU in a world of regions? Considerable, if the EU lives up to the challenge. The EU will have enormous status and influence as the model region, having achieved so much inner positive peace, directly, structurally and culturally. The others are all lining up to learn the tricks, to ask the EU to open the boxes of successes and failures. The world relatively recently having been colonised by the 11 colonial powers, many in the other regions speak their colonial languages, even if the colonisers never bothered to learn theirs, putting them at an enormous advantage in a one-way learning process.

There are some regions in crisis areas where the EU could be a particularly useful conflict resolution formula: a Middle East Community consisting of Israel with its 1967 territorial limit and its neighbouring five Arab states including internationally recognised Palestine: a Central Asian Community of Afghanistan and the regions bordering on Afghanistan, all Muslim, absorbing much of the SCO; a West Asian Community, Turkey–Iran–Pakistan–Afghanistan, all Muslim, possibly via Iraq–Iran–Armenia–Azerbaijan; and a Caucasian Community, Georgia–Armenia–Azerbaijan, with Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. More than mediation, the model function of the EU — interstate and inter-function — becomes a positive peace factor, based as it is on the five conditions offered earlier as a general theory.

The crucial point, however, is how the EU will relate to the other six or seven regions. The five-point model could be used again, but this time at a higher level of complexity, for regions rather than for states. However, as a starter, look at the later four points that are related to negative peace. The idea would be that the EU could play a very positive role if it were non-aligned, basing its security more on defensive defence — ‘homeland security’— than on, say, RDF. Leave that kind of activity to a level higher up, to something more global. The EU should give up old habits of direct interventionist violence, and the structural violence of extracting resources. The EU would have to do what China may be steering towards: self-sufficiency in resources, such as by becoming less oil and gas dependent, which is close to mandatory anyhow, given the need to reduce carbon emission. And the EU has to be useful, which comes easily for such a resourceful region that through colonialism has stimulated demand for its resources and culture.

The big question is how to relate for mutual (symbiosis) and equal (equity) benefit. Any effort to squeeze resources out of the five Third World regions – LA, AU, OIC, SAARC and ASEAN — should be abandoned in favour of exchange at the same level of processing, giving up all protective tariffs against processed products from the Third World. The EU will have to adjust to a decreasing role in total world trade, as South–South trade among the five regions mentioned is bound to increase in relative significance. The same goes for culture: a regional system based on mutual and equal benefit would demand dialogue, mutual respect and curiosity, not one-way culture traffic.

How about homology and entropy — could they be carried over into a regionalised world? One of the gifts of the EU to other regions and subregions would be the division of power between a council for the states (territorial) and a commission for the departments (functional). If that is acceptable a basic condition for inter-regional homology is satisfied, which allows for the possibility of seven or eight commissions working for peace by peaceful means. With the rapid growth of the civil society both regionally and globally, other regions are now approaching the ‘underbrush’ condition so fruitful when the EEC came into being. African, Latin American and Asian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are already lobbying in Brussels, so are European NGOs in East Africa and Addis Ababa. Thus, there is nothing Utopian in what is written in these pages; rather, it is amazing how quickly the world is evolving.

But the real test would be the fifth factor on that list: transcendence. What would be the multilateral organisation at the centre of a regional world? It will be a United Regions, of course. Not a United Nations, whose members are in a waning state system — except for the big ones like the United States, Russia, China and India. The regional system is waxing. There would be no veto power given to one or two regions, but maybe decisions by consensus to start with. There would be a United Regions People's Assembly, maybe based on regional parliaments where they exist and in the future on direct elections. The secretariat could rotate from one region to the other, as has been done successfully in the European Community/Union. There is no need to repeat key errors like the UN veto power, no parliament with a popular mandate or a permanent location.

Building peace

The problems confronting human society are located in the past, in the present and in the future, or two of them, or in all three. The traumas of the past can be addressed by the method of concilia...