![]()

1 Introduction

Lee Marshall

The recording industry has been a major focus of interest for cultural commentators throughout the twenty-first century. As the first major content industry to have its production and distribution patterns radically disturbed by the Internet, the recording industry's content, attitudes and practices have regularly been under the microscope. Underpinning most of this speculation and analysis, however, is not only a belief that the interests of ‘the recording industry’ are synonymous with the interests of the major record labels, but also that ‘the recording industry’, or even ‘the majors’, are entities with consistent goals and practices regardless of specific locality.

This book attempts to offer a better understanding of the recording industry as a whole. Its starting premise is that the recording industry is not a homogeneous entity, having instead different contours in different localities. As well as being a global industry, the recording industry is actually a series of recording industries, locally organised and locally focused, both structured by and structuring the international recording industry. At the heart of the book, therefore, are case studies of seven national recording industries, each specifically chosen to provide a distinctive insight into the workings of the recording industry. The aim of the book is to provide the reader with a sense of the history, structure and contemporary dynamics of the recording industry in these specific territories.

The book has two complementary rationales. The first, already stated, is to provide a more sophisticated account of the recording industry than is often witnessed in contemporary analyses. The record industry has been ‘big news’ over the last decade or so, but the overwhelming focus of analysis has been on the major record labels Universal, Sony, Warner and EMI with their headquarters in Los Angeles, New York, New York and London, respectively. Obviously, the major labels are important – they are called majors for a reason – but focusing too much on the fortunes of these global companies not only overlooks large portions of the recording industry (the vast majority of recording companies are not major labels) but also risks affording the majors a greater coherence than they actually have. The fortunes, strategies and effects of how, say, Warner operates in Finland may not be the same as in Hong Kong. By looking at the recording industry at a more local level we should be able to better understand the interplay of global and local forces that inflect the current tribulations in the recording industry.

The second rationale is the desire to counter the Anglo-American bias of coverage of the music industry. This has been something of a weakness within the study of popular music for many years, but it is particularly acute in studies of the music industry. The fact that there is little English-language work available on the French music industry (which has the third largest recorded music market in Europe) hinders attempts to fully understand the record industry. This is even more apparent in the case of Japan, which has had the second largest recorded music market in the world for many years (likely to soon become the biggest) and historically has contained many features that could soon become more prominent elements of the US and UK industries (such as 360 contracts and tight integration between TV and music companies). The subjects of this book may be far-flung, but they are not trivial; the 7 case studies include 3 of the 10 largest record markets in 2010 and 4 of the top 20.

‘The record industry’ has thus tended to be overly homogenised in scholarly and media accounts of the music industry. As we move in to the twenty-first century, however, it seems that the local is becoming an even more important part of the recording industry. While globally the value of the recorded music market has fallen by roughly 40 per cent over the last ten years, this fall has disproportionately affected ‘international repertoire’. Sales from ‘domestic repertoire’ (i.e. releases by artists from that specific country) have been less badly hit. The table below compares the market share of domestic repertoire from various countries in 1995 (around the peak of the recorded music market), 2000 (when steady decline begins to set in) and 2010.

Table 1.1 Percentage of the overall value of recorded music accounted for by domestic repertoire, 1995–2010

| 1995 | 2000 | 2010 |

| Canada | 10 | 12 | 27 |

| Czech Republic | 29 | 43 | 51 |

| Denmark | 30 | 31 | 57 |

| Finland | 37 | 38 | 51 |

| France | 47 | 51 | 60 |

| Hungary | 27 | 38 | 38 |

| Japan | 76 | 78 | 81 |

| Norway | 19 | 20 | 46 |

| Portugal | 21 | 21 | 35 |

| South Africa | 20 | 23 | 45 |

| South Korea | 57 | 63 | 72 |

| Sweden | 31 | 30 | 49 |

| Switzerland | 6 | 8 | 15 |

Sources: IFPI Recording Industry in Numbers 1999, 2003, 2011.

This is a selective list in order to give a sense of the range of countries that have experienced a relative growth of domestic repertoire. This trend has not occurred everywhere; some territories have witnessed a decline in local repertoire (for example, Hong Kong has declined from 54 per cent in 1995 to 25 per cent in 2010, while Mexico's domestic repertoire has declined from 63 per cent to 43 per cent). Some countries’ local repertoire has virtually disappeared (Singapore, from 41 per cent to 1 per cent; Bulgaria, from 84 per cent to 4 per cent). To explain the situation in individual territories requires detailed analysis of specific circumstances (the raison d’être of this book) but, on the whole, there does seem to be an overall trend of local repertoire increasing its market share in the first decade of the century. It is, of course, an increased share of a smaller market, but the figures suggest that music fans have been more loyal to local artists than global hits (a plausible, but partial, explanation is that listeners are more likely to illegally download music from international mainstream artists such as Lady Gaga). This implies that local artists and, therefore, local industries with knowledge of local music scenes, will become increasingly important.

An important caveat needs to be added to this discussion, however: the data refers to physical product only, not digital. Obviously, this becomes more significant as time goes on and, without detailed analysis, it is difficult to accurately predict the effects of this exclusion. It is plausible, however, that large numbers of local artists are selling music digitally, and, therefore, the overall proportion of local repertoire would still increase (though, counter to this, the vast majority of iTunes’ sales come from major hits rather than the long tail; firm prediction is thus very difficult).

This caveat highlights a theme that recurs throughout this book – that the ‘official’ data produced by the local recording industry associations and the IFPI covers only a portion of the record economy in a particular country. Virtually every case study author makes this point. There are a variety of explanations for why this data can only be partial (discussed in Chapter 3) but the most significant one here is that they only account for record purchases that go through ‘official’ accounting channels, and many forms of music consumption remain at the perimeter of the official industry. By this I do not just mean ‘piracy’ (which is discussed below) but, rather, forms of local, small-scale musical economies beyond the scope of the ‘legitimated’ global industry.

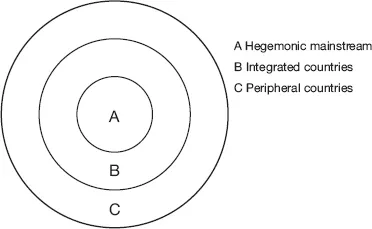

One way to conceptualise this is to conceive of the international recording industry as a series of concentric circles. At the centre is the hegemonic mainstream, the centres of the record industry's power, in territories such as the US, UK, Japan, France and Germany. In these countries, the legitimated industry is extremely important and connected to many forms of musical activity. Next comes what I am referring to as the integrated countries, such as Belgium, Finland, Canada and Singapore. These countries share many similar characteristics with the hegemonic mainstream and their musical economies are thus very tightly integrated with the legitimated industry, although extrinsic companies tend to dominate the intrinsic ones. The outermost concentric circle contains the periphery nations, such as Ukraine. In these countries the legitimated industry enjoys far less influence, with global record labels being just a small part of the local music economy, or not having a presence at all.

Figure 1.1 The international recording industry

This is a crude schema and it has limitations. First, it can be hard to map certain countries on to it, especially those such as Japan and South Korea in which there is a very powerful and legitimated industrial structure that does not necessarily correlate to the four major labels prevalent in the West. Second, it risks overemphasising the power and influence of the legitimated industry at the centre. Even within the hegemonic mainstream there is a great deal of economic activity that occurs outside of the main record labels. However, the concentric circles in Figure 1.1 do give some sense of how the legitimated industry becomes less influential the further one moves away from the centre. As you move towards the periphery, informal economies and local, small-scale economies become more prevalent. This does not make them any less significant – indeed, by keeping money in the local economy rather than seeing it flow to the hegemonic centre, these informal economies can actually be more significant for the domestic economy – it is just that the legitimated industry becomes an increasingly smaller part of the musical economy, and, as such, the power of the major labels to assert their practices diminishes.

The most manifest example of this concerns discourses of piracy. Piracy has, of course, been front and centre in debates about the recording industry within the hegemonic mainstream in the last decade (Chapter 8 on France outlines one of the most significant national responses to illegal downloading) but this kind of piracy is qualitatively different from more conventional forms of piracy that have long obsessed the legitimated industry. In the years BN (Before Napster), the majors’ focus was on ‘hard’ piracy in territories some distance from the hegemonic mainstream and, although piracy closer to home has been the most pressing issue in recent years, more conventional forms of fights against piracy remain. Four of the countries studied in this book have been placed on the United States Trade Representative's Special 301 ‘watch list’ or ‘priority watch list’ for failing to implement or enforce intellectual property protection to a standard satisfactory to the US and its content industries, opening up the possibility of US trade sanctions as a retaliatory measure.

Considered from a different perspective, however, piracy is merely a matter of legitimation. Some forms of music consumption are defined as legitimate while others are determined to be illegitimate. Looking at the issue this way is important because it emphasises that piracy, rather than being any kind of legal absolute, is an ideological construction that requires continual maintenance. The perspective that copyright infringement is important enough to warrant trade sanctions from the US Trade Representative, or for the French state to cut off an individual's access to the Internet, requires persuasion and reiteration from those whose interests it serves. Seen from this perspective, the current crisis of the recording industry is actually a crisis of legitimation: record labels have been unable to persuade consumers that copyright is worth upholding (this is not the same as consumers believing that authors should not be recompensed, merely that copyright is not an effective way to achieve that goal).

For this book, however, the point I want to raise relates to piracy in the peripheral countries, not the hegemonic mainstream, for the question of legitimation in these territories becomes even more acute given that what is occurring can be considered as a form of cultural imperialism, or the importation of Western ideas of intellectual property and authorship into settings where it conflicts with existing social and musical practices. It thus becomes even harder for the legitimated industry to persuade, say, Czech consumers, that the intellectual property rights of some multinational companies are something that they should be concerned about. This is particularly so when the practices of intellectual property enforcement (such as maintaining CD prices at an artificially high level to prevent the sale of cheap imports in the hegemonic mainstream) contradict the material conditions experienced by music consumers (low wages), or when they contradict the experiences of sharing and community that are more explicit elements of ‘non-Western’ musical practices.

Thus, when considering the case studies it is important to maintain a critical perspective towards discussions of ‘piracy’ and not merely to adopt the perspective of the legitimated industry. We need to pay attention to the power dynamics in the relationship between companies based in the hegemonic mainstream and the local recording industries in integrated and peripheral countries. This is the bigger lesson for our understanding of the international recording industries:...