- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume in the yearbook series examines the variety of educational responses to differing forms of diversity within states. The growth of nationalism and regionalism in many parts of the world is considered alongside the emergence of such international structures as the European Community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Yearbook of Education 1997 by Jagdish Gundara in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section III:

National Case Studies

10. Intercultural Education in Canada

Introduction

The discourses of race, ethnicity, culture and education in Canada, as elsewhere, do not have a shared or uniformly accepted terminology. Multicultural education and anti-racist education are commonly used interchangeably, although some authors have argued that they have fundamental distinctions. In Quebec, intercultural education is used instead of multicultural education to explicitly signal that the province’s commitment to inclusivity and equity is located within the structures of a Francophone society. (See Kehoe and Mansfield, 1993, and Moodley, 1995, for a fuller discussion of this debate in Canada.) Indeed, issues of race, ethnicity, culture and education have significantly shaped the Canadian state from its very beginnings. They were a major determinant of the particular form of federalism Canada adopted and the key reason why education was designated a provincial responsibility under The British North America Act, 1867. Notwithstanding such constitutional arrangements, conflict rather than consensus has characterized efforts to reflect the nation’s diversity in provincially funded systems of public education.

Demographic and Cultural Background

Prior to European settlement, an indigenous population estimated to number 200,000 consisted of some 50 distinct cultural groupings with at least a dozen different languages. Four centuries of immigration from around the world have added greatly to that diversity.

The early 17th century saw the start of a period of settlement and exploitation of New France/Canada by French traders and colonizers. This initial period of French settlement was followed by British immigration after Canada was ceded to Britain in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, so that by the time of confederation in 1867 the British population outnumbered the French. At this time, of a total population of some three and a half million people only 8% were of non-British or non-French ethnic origin (Miller, 1989).

The final years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th up to the beginning of World War I saw a second phase of large-scale immigration that significantly altered the cultural make-up of Canada. Between 1896 and 1914 some three million immigrants came to Canada including large numbers of settlers from Northern and Eastern Europe recruited to settle the prairies of Western Canada. Within the period 1901 to 1911, Canada’s population increased by some 43%, and by 1911 people of non-British and non-French origins formed over 33% of the population of the three prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta (Palmer, 1984). Settlement often resulted in initial concentrations of certain nationalities within a particular geographic area, and these block settlements served to facilitate the maintenance of traditional linguistic and cultural patterns (Anderson and Frideres, 1981). This period also saw the arrival of significant numbers of Asian immigrants, many of whom came as contract labourers to build the Canadian Pacific Railway and later settled on the west coast in British Columbia.

While some immigration continued during the inter-war years it was only in the period after World War II that there was a large-scale renewal of immigration that once again significantly reshaped the make-up of Canadian society. In addition to continued immigration from Britain, large numbers of immigrants came to Canada from Europe including Italian, German, Dutch, Polish and Portuguese. Unlike their predecessors, these immigrants settled predominantly in urban rather than rural destinations.

In the mid-1960s in a context of a booming economy and the need for skilled labour to meet the human resource needs of an industrialized and urbanized society, revised immigration legislation replaced existing racially and ethnically discriminatory practices with more universalistic admission criteria based on level of education, occupational skills and demands, and personal adaptability (Moodley, 1995). A consequence of these changes to Canadian immigration policies has been a substantial globalization of immigration into Canada away from the predominantly European patterns of earlier years, contributing significantly to the ‘racial’, cultural and ethnic diversity of the country generally and its major urban centres in particular. (Quotation marks are used here in relation to the term ‘race’ to signal our recognition of the socially constructed nature of the concept of ‘race’, and, as distinct from the term racism, its dubious scientific utility.)

In 1993, 58.4% of the 252,000 people immigrating to Canada came from Asia, with Hong Kong, the Philippines, India and China being the four leading source countries. A further 18% came from Europe, 6.8% from Africa, and 5.6% from North and South America (Statistics Canada, 1994).

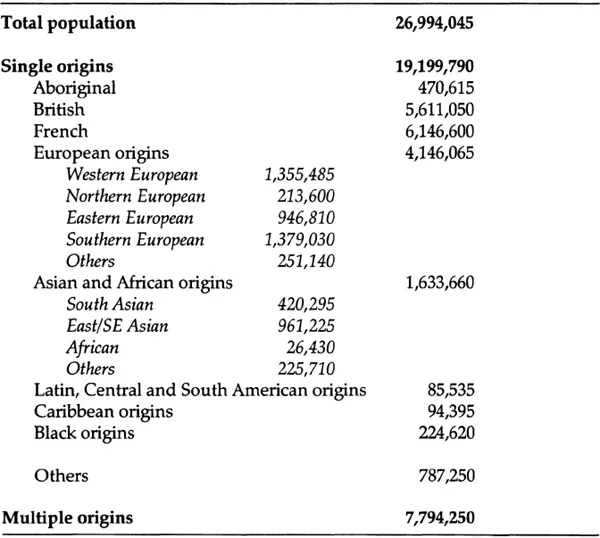

Table 10.1 Canada’s population by selected ethnic origin, 1991

Source: Ethnic Origin: The Nation (1993a), Ottowa: Statistics Canada. Catalogue 93–315.

Structural Responses to Canadian Diversity in Public Education: An Organizing Framework

In looking at the variety of different ways in which cultural differences have impacted upon, and been reflected within, the Canadian public education systems, this chapter is organized around two themes: first, the extent to which cultural differences have found expression in distinct structural and organizational forms; and second, the extent to which various cultural groups have been allowed to participate fully within the existing educational systems.

These two elements provide the basis for a model of intercultural relations developed from the work of Schermerhorn (1970) and applied to education by La Belle and White (1984), shown in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2 A model of intercultural relations

| STRUCTURAL RELATIONS | ||

| Equality | Separate Institutions Different cultural groups exist together in society with separate and parallel sets of institutions and share equally in the resources of the society | Common Institutions Different cultural groups participate in the same societal institutions without discrimination |

| POWER | (Corporate pluralism) | (Liberal pluralism) |

| RELATIONS Inequality | Different cultural groups with separate institutions and unequal power and access to society’s resources | Different cultural groups share a common set of institutions but within them have unequal access to society’s resources |

| (Apartheid) | (Anglo-conformity or ‘The vertical mosaic’) | |

The utility of this model in considering intercultural education in Canada lies in the fact that while it sets up four ‘ideal types’ of intergroup relations, both axes of the model represent in reality a broad continuum of possibilities in terms of degrees of equality/inequality and of common/separate institutions, allowing it to describe many different and shifting arrangements. Furthermore, as Schermerhorn (1970) notes, what becomes of key importance is less the specific location of any particular cultural groups within this typology, but rather the degree of agreement between groups as to the appropriateness of that location.

In the remainder of this chapter something of the range of these struggles and accommodations is described in a variety of different educational settings across the provinces of Canada.

Religious and Linguistic Dualism

While reference to the English and French as Canada’s ‘two founding nations’ is made problematic by its denial of the prior place of Canada’s Aboriginal People/First Nations as well as its failure to acknowledge the presence of non-English, non-French populations, it has been struggles between these two powerful cultural communities around the place of both the French and English languages and Catholicism and Protestantism in Canadian political and constitutional arrangements that have provided some of the most visible and enduring issues in Canadian diversity. Furthermore, it is only these two cultural groups that have seen at least some educational rights entrenched in the Canadian constitution – affording their educational aspirations a degree of legitimacy and security not available to other groups.

Palmer (1984) argues that of the several objectives of the architects of Canadian confederation none was of more importance than accommodating the needs of these two cultural communities. In the British North America Act (1867) it was religion that served as the vehicle for protecting English and French minority education rights with Section 93 of the Act, guaranteeing the right of Catholic and Protestant school systems, where they existed prior to confederation, to continue to exist and to be publicly funded.

In practice these religious rights have not always been respected and Catholic and Protestant schools currently exist in a variety of different forms across the country, reflecting in part their status in each province at the time of confederation and in part the outcome of legal and political challenges since that time (Bezeau, 1989). In Quebec public schooling has traditionally been organized into a denominational system with two confessional school systems (Catholic and Protestant) existing in the urban centres of Montreal and Quebec City, while in the rural districts public and separate/dissentient school systems exist, each confessionally identifiable. The three provinces of Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta have both public (non-denominational) and separate (Catholic and Protestant) systems operating side by side and protected under the law. Yet other provinces, including British Columbia and Manitoba, have a non-denominational public school system, and parents in these provinces seeking a Catholic or Protestant education for their children – like those from other religious backgrounds – have to look to private schools.

Unlike any other province, Newfoundland has multi-denominational school systems. These have included a Roman Catholic system, a Pentecostal system, a Seventh Day Adventist system, and an Integrated system that comprises four denominations – Anglican, Salvation Army, United Church and Presbyterian. However, in 1995 the province has moved to substantially reorganize this system.

The existence of publicly funded Catholic and Protestant school systems has led other religious groups to argue a case for public funding for other religious schools within the public school system (Shapiro, 1985). These arguments have not been successful in Canadian courts and, with the exception of Newfoundland, all religious schools other than Catholic and Protestant schools exist outside of the public school system. Private or independent schools account for only some 5% of the student population in Canada. In most provinces they are eligible for some public funds. In the last decade or so a number of court rulings under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms have made starting the public school day with a Christian prayer illegal – an infringement of the right to religious freedom. Public schools are having either to become increasingly secular or to find ways that recognize the multicultural/multi-faith nature of Canadian society. What the courts will deem acceptable in the latter case has yet to be fully articulated.

While it might have been argued in 1867 that religion served as an effective ‘marker’ of French and English culture in Canada, the constitutional guarantees for Catholic and Protestant schools in the absence of any language provisions have proven to have very limited power to protect minority cultures, specifically French culture in the face of English pressures for Anglo-conformity.

Up until the beginning of the 20th century, schools systems across the country were likely to operate in both English and French where both populations existed, as well as in other languages such as German and Ukrainian (see Bruno-Jofre, 1993). The early decades of the 20th century, however, saw provinces other than Quebec either abolish or place very stringent restrictions on the use of French as a language of instruction in the school. As a consequence, for more than half a century in most provinces in Canada English became the exclusive language of instruction (except where Francophone communities established an essentially ‘underground’ school system within their public schools).

In the second half of this century the struggle around English-French relations in Canada has been largely recast in terms of language rather than religion. Section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, entitled ‘Minority Language Educational Rights’, provides parents who speak the minority official language in their province with specific rights to have their children receive primary and secondary education in that minority language if they so wish. This provision has seen considerable political and judicial activity across Canada to bring existing practice into line with these new constitutional requirements.

This has produced a variety of different institutional and governance forms. Some jurisdictions have responded by establishing distinct programmes for Francophone students in existing schools. Others have recognized the broader educational and cultural arguments that call for separate Francophone schools. In the critical area of governance, recent court decisions pursuant to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms have required several provinces to extend to minority language groups greater control over their own schools and a defined role in the governance of all schools. This has led Ontario, for example, to reserve seats on some school boards for Francophone trustees and to create distinct Francophone school boards in Ottawa and Toronto. Manitoba meanwhile has established a single Francophone school board to serve Francophone schools throughout the province. Quebec has made several attempts to move from a system of school boards based on religion to one based on language, but has only recently been able to do so in a way that respects the constitutional guarantees to both Anglophones and Protestants.

While English and French, the official languages of Canada, have secured constitutional, legal and institutional protections, other ‘non-official’ or ‘heritage’ languages have been afforded far less support. While bilingual programmes – English-Ukrainian, English-German, French-German etc – exist in schools in several provinces, and heritage language classes in an extensive range of world languages exist both as a part of the regular curriculum and as after-hours classes in elementary as well as secondary schools in many provinces (Cummins and Danesi, 1990), their status within the public school system remains much more marginal.

Aboriginal Education

The same concern for minority protection in education afforded to Protestant and Catholic school systems was not applied to the situation of Aboriginal people. It is worth pointing out that, as with other terms in this field, the terminology associated with Canadian indigenous and Aboriginal peoples is complex and shifting. In this chapter we use ‘Aboriginal people’ to refer to all peoples who are the descendants of the original peoples of the land, including Indian, Metis and Inuit people. ‘First Nations’ is a term used to refer to the various governments of Aboriginal people in Canada. The terms ‘Indian’ and ‘Indian education’ are used only as legal terms that refer to specific legal (and not cultural or sociological) designations and arrangements between the federal government and particular Aboriginal people.

While education is generally a responsibility of the provinces in Canada, the historic relationship of Aboriginal people in Canada is with the federal government. The Indian Act, first passed in 1876, has regulated the way in which status Indians have been treated by the government.

For most of Canada’s history, Aboriginal education was controlled by the federal government, delegated to the churches, and shaped by policies and practices which sought to assimilate Aboriginal young people into the lower strata of the dominant society. A number of different institutional forms were experimented with over the years, ranging from local day schools to residential schools often specializing in preparation for industrial, agricultural and domestic pursuits (Barma...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Notes on the Contributors

- Preface

- Section I: Issues in Intercultural Education

- 1. Nation, State and Diversity

- 2. Educational Responses to Diversity Within the State

- 3. Religion, Secularism and Values Education

- 4. Education and Linguistic Diversity

- 5. Educational Contradictions

- Section II: Regional Contexts

- 6. The Commonwealth of Independent States

- 7. The Council of Europe and Intercultural Education

- 8. Intercultural Education and the Pacific Rim

- 9. Intercultural Education in Latin America

- Section III: National Case Studies

- 10. Intercultural Education in Canada

- 11. Intercultural Education in France

- 12. Intel-cultural Education in India

- 13. Intercultural Education in Israel

- 14. Intercultural Education in Japan

- 15. Geopolitics Language Education and Citizenship in the Baltic States

- 16. Intercultural Education in New Zealand

- 17. Minority Education in the People's Republic of China

- 18. Language and Education in South Africa

- 19. Intercultural Education in the UK

- 20. Struggling for Continuity

- Section IV: Afterword

- 21. The Way Forward

- Index