![]()

Chinese Business: Culture, Entrepreneurship or Patronage?

Chinese Business in Malaysia

In multi-ethnic Malaysia, almost all the literature on Chinese business would acknowledge the ubiquitous profile of this community in the economy, even though they now constitute less than a third of the population (see Yoshihara 1988; Jesudason 1989; Hara 1991; Heng 1992). In part, Chinese business ubiquity has been the justification for the government’s concerted attempt to redistribute wealth to achieve economic parity among the major ethnic communities. In effect, this has meant positive discrimination in favor of the indigenous Bumiputera (or ‘sons of the soil’), implemented through the New Economic Policy (NEP) between 1971 and 1990. In 1997, more than 60 per cent of Malaysians were Bumiputeras, a majority of whom were Malay, while the Indians made up most of the remaining tenth of the population.

The introduction and implementation of the NEP was made possible by the domination of the Malaysian state by the United Malays’ National Organization (UMNO), although the government is led by a multi-party coalition, the Barisan Nasional (National Front). UMNO’s leading partners in the Barisan Nasional are also ethnically-based parties, the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). During the 1980s, however, some UMNO leaders began to use party hegemony to secure control over much of Malaysia’s corporate equity. By the end of the 1980s, a ‘new rich,’ i.e. politically well-connected Bumiputeras who had managed to gain ownership of corporate stock, had emerged (see Gomez and Jomo 1997: 117–65). UMNO hegemony and the rise of this ‘new rich’ were widely believed by analysts of the Malaysian economy to have hindered the accumulation and ascendance of Chinese capital in Malaysia.

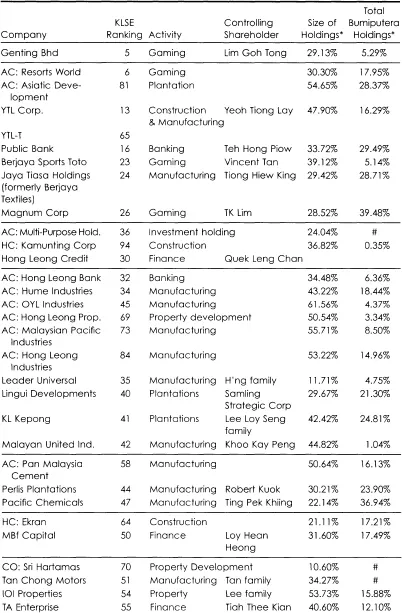

Yet, at the end of the 20-year NEP period in 1990, corporate ownership figures revealed that the proportion of Chinese equity ownership had almost doubled, from 22.8 per cent in 1969 to 45.5 per cent in 1990 (see Table 1.1). During the NEP phase, a number of new Chinese businessmen had emerged as prominent business figures in control of some of the country’s largest companies in terms of market capitalization. Among the most prominent of these businessmen were Khoo Kay Peng, William Cheng Heng Jem, Vincent Tan Chee Yioun, T.K. Lim, Ting Pek Khiing, Joseph Chong Chek Ah, Teh Soon Seng and Tong Kooi Ong. The well-diversified publicly-listed investment holding company, Multi-Purpose Holdings Bhd, which emerged in the mid-1970s during the MCA-led corporatization movement – an attempt to mobilize Chinese financial resources to acquire corporate assets on their behalf – remains one of the largest Chinese-controlled companies in terms of market capitalization. At the end of 1990, the Chinese were estimated to hold 50 per cent ownership of the construction sector, 82 per cent of wholesale trade, 58 per cent of retail trade, approximately 40 per cent of the manufacturing sector and almost 70 per cent of small scale enterprises (see Malaysian Business 16 January 1991).

The validity of these Chinese ownership estimates can, however, be questioned. The government’s ethnic equity ownership figures in Table 1.1 have also been the subject of some dispute. Even the MCA president, Ling Liong Sik, was quoted in parliament in 1989 as stating, ‘[t]he figures don’t agree with ours’ (Malaysian Business 1 July 1991). Ling was, in all probability, suggesting that the amount of equity holdings attributed to the Chinese was too high, while the Bumiputera share of corporate ownership was too low. Leaders of the Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Gerakan), another major party in the Barisan Nasional with mainly Chinese support, have also challenged the government’s ethnic ownership figures. As far back as 1984, a Gerakan report claimed, ‘[o]ur own rough estimate shows that the Bumiputeras have already achieved 30 per cent of national corporate wealth at the end of 1984’ (quoted in Malaysian Business 16 October 1986). Studies have managed to provide evidence that some equity held by nominee companies1 is attributable to Bumiputeras, particularly politicians or politically-connected individuals (see Gomez 1990). In this respect, it is noteworthy that between 1990 and 1995, Chinese share of equity stock fell by almost five percentage points, from 45.5 per cent to 40.9 per cent (see Table 1.1). Other studies have suggested that despite significant Chinese ownership of corporate equity, dominance over the economy is now in the hands of a Malay political elite following the successful implementation of the NEP (see, for example, Gomez 1990, 1994; Jomo 1990, 1994; Gomez and Jomo 1997). A more credible indication of Chinese influence in the economy is provided by listing the number of Chinese-controlled companies among the top hundred companies on the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange (KLSE) (see Table 1.2).2

Table 1.1 Malaysia: Ownership of Share Capital (at par value) of Limited Companies, 1969–95 (percentages)

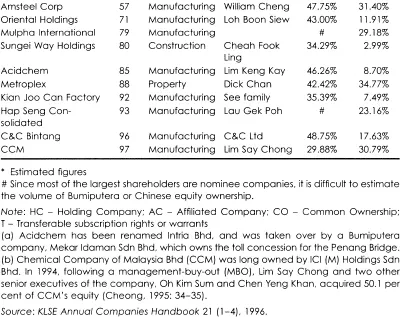

The most striking point that emerges from Table 1.2 is that almost 40 per cent of the top hundred companies are under Chinese majority ownership. Of these 40 companies, almost half are involved in manufacturing activities, i.e. they are listed as industrial and consumer products counters of the KLSE. Yoshihara (1988) suggests that one reason why Southeast Asian capital is ‘ersatz’ is the lack of development of a productive manufacturing base by most of the region’s leading companies. From another perspective, since the implementation of the NEP, the Chinese have generally been cautious about investing in manufacturing as the government has strongly advocated greater Bumiputera participation in this sector and has shown a preference for foreign investors to forge ties with state or Bumiputera-owned enterprises to secure government economic benefits and concessions (see Jesudason 1989; Yasuda 1991). In its endeavor to develop Malaysia’s manufacturing sector, the government has provided concessions in various forms, including tariff protection, depreciation allowances, tax breaks and licences, many of which, it is widely presumed, have not been captured by the Chinese. In 1970, Chinese ownership of manufacturing companies amounted to 22.5 per cent, Malay ownership was a mere 2.5 per cent, while the bulk was under foreign ownership (Low 1985: 26). Yet, by 1990, Chinese ownership of the manufacturing sector was estimated at 40 per cent (see Malaysian Business 16 January 1991). Between 1970 and 1980, the average annual growth rate of manufacturing output exceeded 10 per cent; by the end of the 1980s, manufacturing had become a major net foreign exchange earner. By 1996, manufacturing’s share of Malaysia’s GDP had increased to over 30 per cent.3

Table 1.2 Breakdown by Ethnicity of Equity Ownership of Chinese Companies Among the Top 100 Publicly-Listed Companies in Terms of Market Capitalization

This raises two questions: How has Chinese capital managed to develop its corporate holdings, despite having to operate in the NEP environment that seemed inimical to its interests? Does this suggest that intra-ethnic business linkages have enabled Chinese capital to develop its corporate holdings in Malaysia? This volume is an attempt to address these questions, by tracing the growth of the largest Chinese enterprises in Malaysia.

Literature Review: Culture, Ethnicity and Class

Since the early 1990s, a spate of new studies has emerged, arguing that ethnic Chinese ‘networks’ are spearheading Asia’s economic growth and becoming a major global force (Kotkin 1993; Nasbitt 1995; Rowher 1995; East Asia Analytical Unit 1995; Weidenbaum and Hughes 1996; Hiscock 1997). To support this contention, a variety of figures has been cited. Weidenbaum and Hughes (1996: 24–5), for example, refer to the World Bank’s estimate that the combined economic output of the businesses of the approximately 50 million ethnic Chinese in Asia outside of China – about 23 million in Southeast Asia, 20 million in Taiwan and the rest in Hong Kong – approached US$400 billion in 1991.4 In 1994, the Far Eastern Economic Review’s (17 July 1994) conservative estimate of Southeast Asian investment in China was US$8 billion, while total investment from Taiwan was US$5.4 billion, with Hong Kong investing US$40 billion. In 1996, Asiaweek (19 July 1996) estimated that between 1978 and 1996, of the US$120 billion invested in China, almost 80 per cent of the total investment had originated from ‘overseas Chinese’. Disclosure of such investment patterns in China has fed speculation that the Chinese of the diaspora are channeling funds to the mainland. By 1997, four World Chinese Entrepreneurs’ Conventions and 21 World Chinese Traders’ Conferences had been convened and attended by Chinese from all continents, suggesting that many ethnic Chinese were beginning to consider whether their common ethnic identity could be a means to facilitate business ties.

Another body of literature has fed speculation that contemporary Chinese capitalism has distinctive characteristics which have facilitated its growth. In particular, the institutions, norms and practices of ethnic Chinese have been identified as reasons for the growth of their enterprises and the emergence of Chinese business networks. Ethnic networks, based on trust and kinship ties, have reduced transaction costs, increased co-ordination and diminished risks (Redding 1990; Whitley 1992; Kotkin 1993). Fukuyama (1995) also subscribes to such a cultural perspective, but argues that there is very little trust among Chinese outside of immediate family members. For Fukuyama, equal division of family wealth among sons tends to undermine the development of Chinese business groups. Such a practice also leads to dissipation of corporate holdings and competition among family companies, hindering the development of large Chinese corporations. There is little empirical evidence to support either of these two hypotheses in the Malaysian context, particularly among larger Chinese enterprises.

This strengthens the growing body of literature that contests the presumptions that the values and socio-economic institutions characteristic of some Chinese are universal within the community and that ethnic Chinese overseas are identical with those in China (see, for example, Hodder 1996). Such homogenizing assumptions fail to take into account the specific and particular experiences of Chinese business communities in different countries. In Malaysia, as Jesudason (1997) has noted, cultural changes had begun to weaken ethnic solidarity in business even before implementation of the NEP; clan and guild associations, for example, have diminished in importance among the Chinese. Moreover, such static general cultural assumptions can be contested by reference to cross-border comparisons. Why, for example, have ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs in Thailand managed to accumulate a far greater proportion of corporate equity than, say, the far more numerous Chinese in Singapore? Yet, Sino-Thais constitute just 10 per cent of the Thai population while more than 75 per cent of Singaporeans are ethnic Chinese. This suggests that the use of culture as the primary conceptual tool to explain the growth of ethnic enterprises is problematic.

Another major problem in much of the current literature is that all Chinese are treated as a homogenous and monolithic group. It is possible, however, to disaggregate the Chinese into sub-ethnic groups that have played different roles within the larger Chinese ethnic community. In Malaysia, which probably has among the largest number of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia, the community has not managed to transcend internal divisions to act as a unified ethnic force, even in the face of blatant ethnic discrimination by the state. Among the major dialect groups in Malaysia – including Hokkiens, Cantonese, Teochews, Hainanese and Hakkas – the Hokkiens comprise the largest sub-ethnic community, and have played the most prominent role in business. Some Hokkiens have also had a long tradition of being involved in trade. Particularly in the Malayan peninsula, Yong (1987: 10) noted that Hokkiens ‘had been the merchant princes during the 19th century, and in the 20th century dominated the more modern sectors of the economy, such as banking, insurance, shipping, rubber-milling and manufacturing, and the export and import trade.’ 5 Recently, it seems that the most effective and long-term business co-operation among Chinese in Malaysia and elsewhere in East Asia has been among the Foochows (Asian Wall Street Journal 21 December 1994).6

Another significant cleavage among the Chinese which is ignored in much of the existing literature is class difference. In Southeast Asia, Chinese in Thailand comprise about 10 per cent of the population, but own approximately 85 per cent of the economy. In the late 1980s, Sino-Thai business groups owned 37 of the 100 largest companies in Thailand; most of this wealth was concentrated in the hands of just five key Teochew families (Suehiro 1989; Lim 1996). Ethnic Chinese constitute only three per cent of Indonesia’s 182 million population but own an estimated 70 per cent of the country’s corporate assets. One Indonesian, Liem Sioe Liong, the second wealthiest man in Southeast Asia after the Sultan of Brunei, controls the Salim Group which recorded sales estimated at US$9 billion in 1992, then approximately five per cent of Indonesia’s GDP (Business Week 11 November 1991). About two per cent of the Filipino population is believed to be ethnic Chinese, but they own about 40 per cent of corporate equity (Lim 1996).7 In Malaysia, by the mid-1990s, although the country’s 28 per cent ethnic Chinese owned 41 per cent of total corporate equity, there is evidence that much of this wealth is highly concentrated (see Hara 1991; Heng 1992; Gomez and Jomo 1997). Recent studies of the political economy of the region in general, and of some of the largest Chinese companies in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand in particular, also provide evidence that Chinese business growth has been determined not by ‘Chinese’ traits, but by their ability to forge close ties with the indigenous elite (Robison 1986; Yoshihara 1988; Suehiro 1989; Hutchcroft 1994; Gomez and Jomo 1997).

Popular notions like ‘global tribe’ and ‘bamboo network’ refer mainly to the business activities of the Chinese elite who owns much of this wealth – Malaysia’s Robert Kuok and Quek Leng Chan, Indonesia’s Liem Sioe Liong, Eka Tjipta Widjaja and the Lippo Group, Singapore’s Ong Beng Seng, the Philippines’ Henry Sy and John Gokongwei, Thailand’s Sophonpanich family and Charoen Pokphand group, and Hong Kong’s Li Ka Shing and Lee Shau Kee (see Kotkin 1993; East Asia Analytical Unit 1995; Weidenbaum and Hughes 1996). The business deals among these businessmen have been the primary basis for arguing that there exists growing business cooperation in East Asia among Chinese enterprises which will ensure their emergence as a dynamic global business force.

Kotkin has been principally responsible for the argument that a common ethnic identity and culture has inspired the creation of intra-ethnic business networks. Kotkin asserts that ‘global tribes combine a strong sense of common origin and shared values’ and that ‘success in the new global economy is determined by the connections which immigrant entrepreneurs carry with them around the world’ (Kotkin 1993: 4). Kotkin seems to be influenced by a number of ideas in the literature on ethnic enterprises. One major influence is the Weberian view that belief systems drive entrepreneurial behavior in capitalist economies. Weber argued that the ‘Protestant ethic’ encouraged hard work and economic rationality, thus explaining the industrial transformation of Western Europe. Weber also argued that the development of capitalism in China had been hindered by Confucian traits, i.e. a kinship system based on the extended family, bureaucratic centralization of power in a patrimonial state that obstructed development of a capitalist class, and a...