![]()

The geography of collective consumption | | 1 |

A book entitled Cities and Services: The Geography of Collective Consumption must at the outset address two important questions: first, just what is meant by the term ‘collective consumption’, and second, why is it appropriate to consider this phenomenon from a geographical perspective? After considering these issues, this chapter will lay the foundation for the rest of the book by outlining the history of geographical approaches to the study of collective consumption, and then considering the basic features of British and American local governments – the main bodies responsible for the administration of collective services. Allied to this is a discussion of why the book concentrates on cities and what is meant by the term ‘urban’ in the context of collective consumption. Finally, there is a brief outline of the major theoretical perspectives currently available for explaining the distribution of collective consumption within cities.

The meaning of collective consumption

In recent years, the notion of collective consumption has become intimately linked with the work of Castells (1977), whose ideas have attracted considerable comment and criticism. Unfortunately much of this debate is not particularly illuminating, since many of the protagonists appear to have been talking at cross-purposes, or else moving in ever-diminishing circles of semantic definition. The debate does raise important issues, but since these are bound up with the nature of Marxist explanations of collective consumption, these issues will be held over until Chapter 5, where they will receive extended treatment.

In order to answer the question ‘What is the meaning of collective consumption?’ a more useful starting point is to consider some of the basic features of advanced industrial societies. In essence, these societies are involved in two basic processes. The first process is that of production – making all the goods and services required by the members of the society in order to keep the society in existence. The second process is that of consumption – the utilisation of these goods and services by the members of the society. In order to link production and consumption there have to be some criteria for regulating the distribution of these goods and services. In advanced industrial societies there are two basic systems used to co-ordinate these processes.

The first system, to be found in communist societies, is usually termed the command system within which both production and consumption are regulated by a central bureaucracy under the control of the Communist Party. The criteria used to distribute services may be numerous, such as efficiency, equality, the self-interest of the élite groups, or the long-term survival of the society.

This book is, however, primarily concerned with Western capitalist economies, and in particular Britain and North America, where a second system, based on market exchange principles, is dominant. Under the market system, in its extreme form, both production and consumption are left to the ‘invisible hand’ of the private market. In theory, what is produced is dependent upon consumer demand, which reflects individual preferences for goods and services translated into purchasing power. This demand will, in turn, depend upon the price asked (since the ‘law of demand’ indicates that people will consume more of a good when it costs little than when it is expensive), and also upon the amount of the good that is supplied so that, in theory, there will be an equilibrium between supply and demand. According to neo-classical theory, markets will therefore automatically adjust to changes in supply and demand to find an equilibrium solution. The distribution of goods and services is therefore primarily based on the ability of individuals to pay.

This approach is based on consumer sovereignty – the idea that the individual is the best judge of his or her own welfare. Furthermore, it rests upon a basic philosophy of methodological individualism, which assumes that persons are free to make rational decisions to maximise their utility on the basis of their own preferences. Even proponents of the approach would, however, accept that the ability of individuals to maximise their utility is not entirely free. What is produced is often dependent upon the requirements of the producers, and consumer wants are affected by advertising. Thus – as will be elaborated later – individual utility maximisation is inevitably constrained by social and economic forms beyond individual control.

Despite the dominance of market-exchange principles in capitalist societies a substantial – and, until recently, ever-increasing – proportion of goods and services within these economies are now allocated by their public sectors on non-market criteria. In order to understand why this is the case it is necessary to begin by considering the difference between private and public goods.

The pure theory of public goods

Samuelson (1954; 1955) was one of the first economists to discuss in detail the difference between public and private goods, and, as such, laid the foundations of what is termed the ‘theory of public goods’. A private consumption good he defined as one which can only be consumed by one person or at most a small group of people such as in a family or household. Food, clothing, housing, and consumer durables such as cars and radios are obvious examples. Consumers have widely differing preferences for these goods, both in terms of quantity and quality, and consequently they are amenable for distribution by private markets.

Public consumption goods, in contrast, have properties which make it impossible for distribution by private markets. Musgrave (1958) elaborated Samuelson's ideas to define three basic criteria which define pure public goods. First, there is the concept of joint supply (or non-rivalness) which means that, if a good can be supplied to one person, it can also be supplied to all other persons at no extra cost. Second, there is the idea of non-excludability whereby, having supplied the good to one person, it is impossible to withhold the good from others so that those who do not wish to pay for it cannot be prevented from enjoying its benefits. Third, there is the notion of non-rejectability, which means that once a good is supplied it must be equally consumed by all, even those who do not wish to do so.

It is important to note that the pure theory is based upon the characteristics of the goods and services themselves and not whether they are produced within the public or private sectors of the economy. In reality, many goods are produced by nationalised public sector companies but are distributed within private markets (Renault automobiles being a classic example). Conversely, many products – such as medicines and spectacles for example – are manufactured by privately owned companies, but distributed on a non-market basis within the public sector. The Samuelson-Musgravian approach is concerned with those situations where the characteristics of the good lead to market failure so that there is no way of preventing ‘free riders’, who contribute nothing, from consuming the product. Under these circumstances a rational individual wishing to maximise his utility would withhold from paying anything for a public good. The most commonly cited example of a public good is defence. Despite the creation of ‘nuclear-free zones’ in over 150 British local authorities, it is impossible for a city to ‘opt out’ of the added protection or vulnerability engendered by nuclear missiles. Indeed, it is the impossibility of rejecting this type of good which – together with horror at the prospect of nuclear war – has aroused such enormous controversy over the location of Cruise missiles in Britain.

Reasons for a geographical perspective

This immediately brings us to the reasons why geographers are interested in the distribution of public goods and services, for the factors which most commonly undermine this theoretical purity are of a geographical nature. Drawing upon the pioneering work of Tiebout (1956) and later Teitz (1968), we can divide these factors into three main types.

First, there is the phenomenon of jurisdictional partitioning. Most countries of whatever economic system, are divided into smaller local government jurisdictions or administrative areas. For a variety of economic, social, political and administrative reasons, which are described in Chapter 2, these local government units vary enormously in the quantity and quality of public goods and services they provide. Indirectly, then, the amount of public sector resources an individual receives is often dependent upon his or her location.

A second major reason is because of tapering. Within these jurisdictions many public services which are theoretically available to all sections of the community, such as parks, libraries, swimming pools and sports centres obviously have to be located at particular points – hence they are often termed ‘point-specific’ services (Wolch, 1979). Even if these services are provided free at the point of supply, individuals will typically have to bear the cost of travelling to the facility. We know that, in general, costs, together with time and effort, tend to increase with distance travelled. Furthermore, the so-called ‘law of demand’ suggests that as costs increase so the quantity of a good that is consumed will decrease. All this means is that with a fixed budget of money, time or effort, the amount of a public good, or the frequency with which it is consumed, will decrease with increasing distance from the facility. Eventually a point may be reached where the costs are such that the service is not utilised. Clearly, in these circumstances geography or distance-decay effects undermine the criterion of non-exclusion in the supply of public goods. Similar principles apply if the service is what Wolch (1979) terms an ‘outreach’ service, that is, one that is delivered to the consumer, such as fire protection or an ambulance service. Here the costs are typically borne by the supplier of the public good so that it costs more to supply recipients distant from the facility supply base. Furthermore, the quality of the service will also vary with distance from the base. Some areas may be less well-protected by police patrols while emergency services will take longer to reach more distant locations. In this case, then, distance also undermines the criteria of joint supply (an identical quality of good for all at no extra cost).

Externalities provide a third reason for a geographical perspective. An externality, in broadest terms, is an unpriced effect. Many activities in advanced industrial societies have side effects which are not reflected in costs or prices. Geography is again important because these activities take place at specific locations, and the side effects will extend outwards from these locations in a spatial field. Once again these effects will tend to diminish with increasing distance from the source of the externality. These effects may be positive, producing benefits for the surrounding area, or negative, producing disbenefits. Activities producing negative externalities are sometimes termed noxious facilities: typical examples would be the smell from refuse tips, or the noise from roads and airports. Activities with positive externalities are sometimes termed salutary facilities, and include the quiet associated with parks and open space, or the social mobility promoted by good-quality educational facilities.

There are many complex issues involved with externalities which are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3 but a number of points should be noted in this introduction. First, as in the case of jurisdictional partitioning and tapering, the importance of externalities, whether positive or negative, depends upon individual value systems. There may be wide differences between areas, but also between the individuals within the same area, regarding the importance of these side effects. Activities which arouse opposition in some localities may be treated with indifference elsewhere. Frequently it is the impact of these activities upon house-values in owner-occupied areas which is the main preoccupation of local residents. This means that opposition is often greater before a new activity is located in an area, or when a valued facility, such as a school, is threatened with closure or withdrawal. Clearly many public sector facilities will have an important impact upon the well-being of local communities.

It should be clear that externalities are related to the tapering effects described earlier. Positive externalities may accrue to an area because of the ease of access to valued facilities such as libraries, sports centres and parks. However, externality effects need not exist only within local government boundaries but may have impacts which extend across jurisdictional boundaries. The term spillover is often used to describe a situation in which facilities are provided in a local government area and consumed – but not paid for – by ‘free riders’ from other political jurisdictions. Major recreational facilities, shopping centres and roads are examples of services provided by large cities but widely enjoyed on a regional basis by those who live outside the city boundaries. Conversely, certain activities may create negative side effects in nearby government units, as when heavy industries produce pollution or when untreated sewage is pumped into the sea and washed along the coast!

Some complications

It takes little thought to appreciate that, given the widespread effects of jurisdictional partitioning, tapering and externalities, few goods will possess all the criteria specified by Samuelson and Musgrave. Even the extent to which a nation is defended can be expected to vary from one area to another; under attack, certain peripheral regions may be sacrificed to preserve a core region from invasion. As Samuelson (1955) himself noted:

Obviously I am introducing a strong polar case ... the careful empiricist will recognise that many – though not all – of the realistic cases of government activity can be fruitfully analysed as some blend of these two extreme polar cases. (Samuelson, 1955:350).

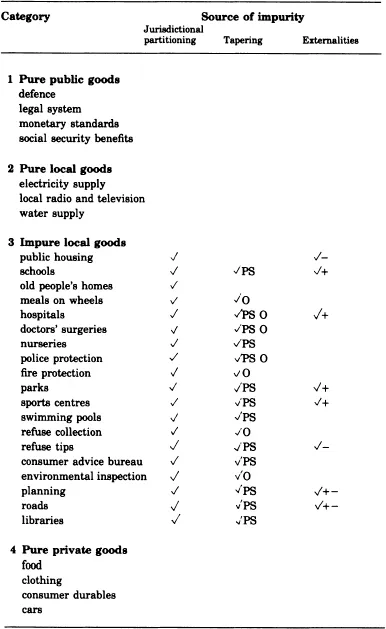

Table 1.1 is an attempt to present goods and services along such a continuum. At the top of the table (category 1) are the public services which possess many or all of the pure Samuelson-Musgravian characteristics, including defence and the legal system. At the bottom of the table are the pure private goods. Category 2 consists of pure local goods which, generally speaking, are freely available to all individuals at equal cost within particular local government units or administrative areas. From a spatial perspective the main interest therefore focuses upon category 3 which contains various forms of local public goods and services which are made impure through various combinations of jurisdictional partitioning, tapering and externalities. Table 1.1 also attempts to indicate the main sources of this impurity. It can be seen that all the services are likely to display geographical variations because of their administration by decentralised political and administrative units. As will be revealed in Chapter 2, these variations are greater in the case of some services than others. Tapering effects are also widespread irrespective of whether the service is ‘place specific’ or ‘outreach’ in character, and some services such as hospitals are a combination of both. Externality effects are also widespread, although in this table we have included only those which are likely to have the greatest effect on public opinion.

Some public facilities such as schools, hospitals and parks, generate pressure groups in favour of their existence, whilst facilities such as public housing or refuse tips are likely to meet resistance from the population of an area if they are proposed in the vicinity. In some cases – roads, for example – there may be groups for and against depending to some degree on the distance of individuals from the facility. Regulatory services such as planning can, of course, have either a positive or negative impact.

It should be stressed that local services are much more extensive and complex than is implied by this list, which is used merely to illustrate the theory of public goods. Although this type of framework is a useful starting point, defining what is meant by collective consumption is much more complex than the theory of public goods would suggest. The crucial point is that there are few technical reasons why many goods such as housing, education, electricity supply, roads or health care should be allocated by the public sector in preference to the private sector. This is, of course, revealed most strikingly by comparisons between Britain and the United States.

Key

| indicates potential source of impurity |

| PS | place specific service |

| O | outreach service |

| + | generally positive externalities |

| - | generally negative externalities |

Table 1.1 A continuum of goods and services ranging from the purely public to the purely private. (After Bennett, 1980)

Indeed, such are the limitations of the theory of pure public goods that Samu...