![]()

1 Getting young adults back to work: A post-industrial dilemma in Japan

The issue is not that NEETs do not work. They simply cannot work.

–Genda Yūji (Genda and Maganuma 2004:244)

How did the state, interested experts and the media, as well as youth supporters respond to the sudden rise of worklessness among young adults in early twenty-first-century Japan? This is the driving puzzle around which the present volume is organized. The answer that emerges is complex, but it has two essential facets. First, we find that actors within the central government, affiliated experts and the mainstream media collaborated to deliver what may be called ‘symbolic activation’. This was an arrangement whereby, instead of carrots and sticks, or handouts made conditional on participation in official activation measures, certain symbolic labels were deployed to direct formally inactive young adults back into the (low-wage) labour markets. Second, we discover that, in a striking challenge to state policy, youth supporters and their managers implemented practices that contrasted quite dramatically with, and highlighted alternatives to, the dominant (international) paradigm of activation. Under the guise of state-led independence support, what in fact took shape were new kinds of ‘communities of recognition’ as well as a youth work methodology of ‘exploring the user’ (i.e. the support-receiver). It is this second dimension in how Japan responded to youth joblessness that suggests promising long-term solutions to the post-industrial youth employment dilemma that virtually all advanced nations currently face but which none has yet seriously addressed.

This introductory chapter begins by setting out the essential socio-economic as well as ideological (and ideational) context to the emergence of youth activation in Japan. This necessarily requires a discussion on how other countries have responded in the face of similar problems, including the key policy ideas they have favoured. Because highly charged youth labels such as freeter and NEET came to play a central role in the domestic Japanese policy process, two further sections are dedicated to surveying these controversies. Set out next is the key argument that Japanese government-led efforts to get disengaged youth ‘back to work’ are best understood as constituting a system of symbolic activation. The present chapter concludes with a description of research design matters and the Japanese youth support field, followed by a synopsis of the entire book.

What kind of dilemma?

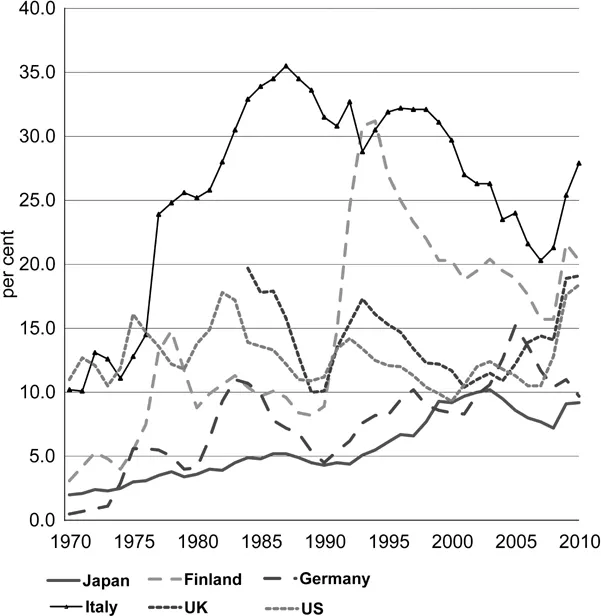

Though rarely phrased in these exact terms in public debate, what may be called ‘the post-industrial dilemma’ is a helpful starting point for understanding why pre-existing policies and practices around youth and employment are being thought about anew in advanced countries around the world, including Japan. By this dilemma I mean the challenge of maintaining socially acceptable levels of sufficiently paid employment in the face of lower GDP growth rates, borderless finance, international competition, technological transformation and complex labour market change. Youth, more than older cohorts, have had to cope in a post-industrial society where unemployment is on the rise (Figure 1.1) and where employment in agriculture and manufacturing has diminished to the point that the majority of jobs are to be found in the more fluid service sector (Figure 1.2). Indeed, the terms ‘post-industrialism’ (Bell 1973) and ‘post-industrialization’ are usually employed to denote the increasing centrality of the service sector following processes of deruralization and deindustrialization, though the concept is used quite variably by different authors (see, for example, Esping-Andersen 2009 regarding the impact of women’s growing participation in paid work and Pierson 1998, who stresses the implications of population aging). I use ‘post-industrial’ primarily to point to labour markets that are service sector-oriented and more fluid than those of an industrial era.

Figure 1.1 Youth unemployment trends, 1970–2010 (15-to 24-year-olds), %

Source: OECD StatExtracts (downloaded 22 March 2012)

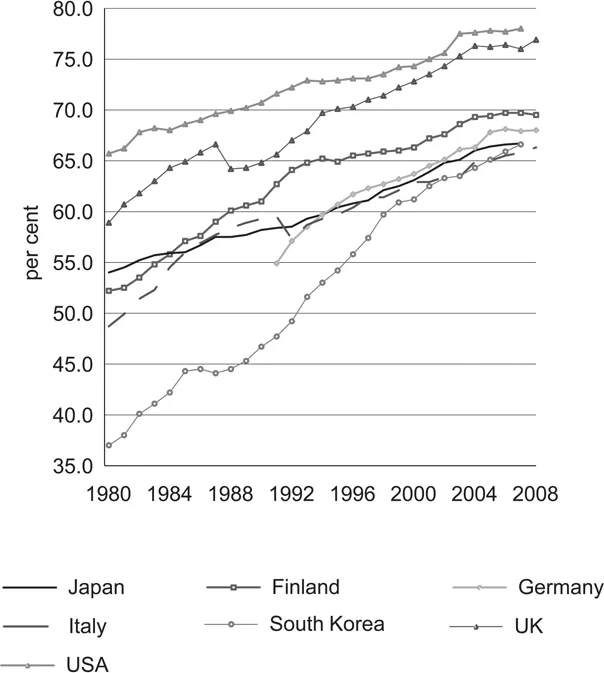

Figure 1.2 Trends in service-sector employment as a percentage share (%) of total employment in selected OECD countries

Source: World Bank (2010)

Although a post-industrial society need not in theory be perpetually marred by high unemployment, the dilemma of how to maintain politically acceptable levels of sufficiently paid employment – especially among young adults – remains currently a major issue for nearly all advanced nations. The roots of this dilemma are complex, but, due to the centrality of the service economy, where productivity growth (as conventionally measured) is limited and a high volume of relatively unskilled labour is demanded, it has been suggested that there may exist an unavoidable trade-off between ‘either joblessness or a mass of inferior jobs’ (Esping-Andersen 1999:111). We will later review key responses that have been proposed in the face of post-industrial changes in the West, but first let us take a more detailed look at the case of Japan. To begin with, when and how did the post-industrial employment dilemma appear there, specifically in relation to young people?

Changes in the labour markets, the organization of work and transitions

In terms of timing, it was the bursting of the real estate bubble at the beginning of the 1990s and the subsequent long recession that ushered in the most challenging and definitive period of post-industrialization in Japan (see Schoppa 2006; Peng 2004).1 To cut a very long story short, this period had major impacts on Japan’s youth labour markets, on the organization of work and on the (previously) institutionalized school-to-work transition system, as follows.

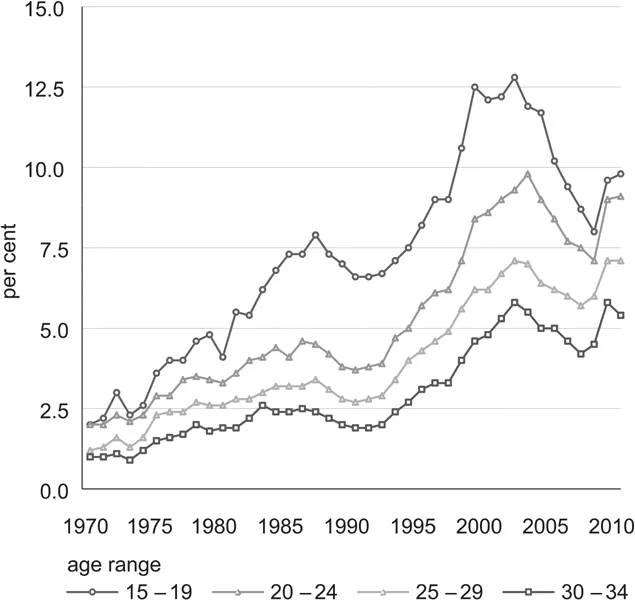

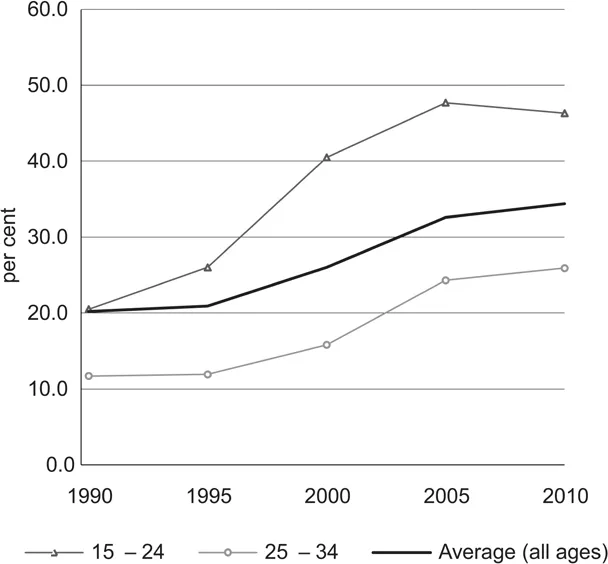

• Youth labour market trends. Strikingly, unemployment rates doubled, or more than doubled, for all age groups between 1990 and 2003, though those in their teens and twenties were particularly hard hit as they already suffered from higher than average unemployment at the beginning of this period (Figure 1.3). The consequences of early joblessness tend to be so severe in Japan that the worst-hit cohorts of new graduates would eventually come to be dubbed a ‘Lost Generation’. Parallelling changes in levels of unemployment, the share of part-time work and other forms of irregular employment (hiseiki koyō) also doubled in the 1990s and the early 2000s following successive labour law changes that made it easier to hire non-standard workers in both the manufacturing and service sectors (Figure 1.4; Weathers 2001; Gottfried 2008:189). Notably, a particularly high share of 25–34-year-old female employees – over two-fifths – came to be employed as irregulars (Statistics Bureau 2011). This substantial deregulation of the labour markets meant that a large portion of Japanese youth came to live outside the constraints as well as the strong social protections of the life-time employment system (shūshin koyō seido) – a key pillar of economic independence and well-being in the postwar period (Goodman and Peng 1996) – with sharp consequences for inequality.2

• Underlying the quantitative surge in non-standard work was an ongoing process of post-industrialization whereby Japanese service employment increased by nearly ten percentage points between 1990 and 2007, to a total of 67 per cent of all workers. In the same period, employment in manufacturing decreased from 34 per cent to less than 28 per cent (World Bank 2010), suggesting a significant qualitative shift in the nature of employment opportunities.

• The reorganization of work. The above structural changes have been accompanied by a broader reorganization of work whereby the entire Japanese employment system is perceived to have come under threat. On a symbolic level, perhaps the greatest challenge has been delivered by ‘the freeter lifestyle’ among young adults (Kosugi 2008), as described in more detail below. Dispatched workers (haken shain) have dealt another blow to Japanese employment as conventionally envisioned, reflecting the demise of company belongingness and the rise of ‘a self-oriented process where occupational specialization assumes greater importance and the way people work is a matter of free choice’ (Fu 2011:128). Yet job mobility has increased somewhat also among ‘standard’ seishain workers with permanent contracts.3 In light of higher overall mobility, it seems increasingly more appropriate to speak in terms of ‘long-term’ rather than ‘life-time’ employment relations as characterizing the core of the Japanese labour market.

• A host of other subtle changes have unfolded. In the 2000s, employers used the term sokusenryoku to express a growing interest in recruiting flexible workers who could make themselves ‘instantly useful’, usually outside the framework of the long-term employment system. This Japanese notion of employability is mirrored in the increasing popularity of various portable qualifications (shikaku) and vocational institutions that provide related training (see Borovoy 2010). Relatedly, the personal qualities of ‘self-directedness’ (shutaisei), ‘individuality’ (kosei) and ‘creativity’ (sōzōryoku) as well as strong communication skills have been framed as essential for success in the new economy (see Cave 2007 regarding the roots of these terms in 1980s’ educational discourse). Lacking clear definitions, these terms have left many students confounded – including those whom I taught at Kyoto University, an elite institution, in the late 2000s – especially when actual job interviews have revealed a persisting corporate preference for obedience and ‘cooperativeness’ (kyōchō sei) over self-assertiveness. It has been felt that only those who can skillfully ‘read the situation’ (kūki wo yomu), balancing conventional and newly demanded attributes, are likely to succeed in the new economy. There is evidence from psychological experiments that much of the confusion that many young adults now feel springs partly from a growing discrepancy between explicitly held values and behavioural scripts, emphasizing independence, and values and scripts that are held at the implicit level, which still tend to emphasize interdependence (Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida 2011). The Westernized, though uniquely articulated, language around work may thus be as significant a factor in the labour market experience of young people as are the associated structural changes.

• It is important to add that, for those who fail to enter the core workforce in today’s Japan, employment conditions can be relatively harsh: long hours are expected even of nominal ‘part-timers’; labour law violations are widely tolerated (especially when it comes to working hours); and there are limited institutional protections and oversight for the 80 per cent of workers who do not belong to a labour union (Weathers and North 2009). While too many and complex to sufficiently review here, the narratives of the youth support staff and supported youth whom I met during fieldwork reflect many of these issues (see Chapter 6 in particular).

• The erosion of the school-to-work transition system. Japan’s sophisticated institutional school-to-work transition machinery (mentioned in the Preface) has likewise changed with post-industrialization, leading authoritative scholars to write it off as ‘dysfunctional’ (Honda 2004). Up to the 1980s, it could still be said that school-to-work transitions unfolded pre-dominantly through extensive institutional mediation, with schools and companies playing a major role under the coordination of public employment offices (known in Japan as Shokuan or Hello Work). At this time, school-mediated transitions (gakkō keiyu no ikō) were underpinned by semi-formal employment contracts (jisseki kankei) whereby schools agreed to recommend suitable students to companies who in turn agreed to recruit a consistent number annually regardless of actual labour demand, based on long-term trust relations (Rosenbaum and Kariya 1989). Hiring decisions were made several months ahead of graduation and the practice of periodic mass recruitment (ikkatsu saiyō) meant that the vast majority of students could enter their new jobs according to a unified schedule at the beginning of April.

• Key factors that have eroded this once-functional system include the increase in non-standard employment as well as the growing popularity of higher education and post-secondary vocational schools. Non-standard employment, now the destination of a large share of high school graduates, is by definition outside the scope of the established system. Those moving into positions here tend to find them through earlier part-time jobs – an alternative recruitment channel (Brinton 2001) – or through publicly available job adds. Since just about half of all high school graduates in Japan now proceed to university (almost always at 18 years of age), while another fifth enter post-secondary vocational schools known as senmon gakkō (Goodman, Hatakenaka and Kim 2009), most youth entirely bypass institutionalized school-to-work transition channels at the high school level. They do come within the scope of various ‘career services’ at tertiary institutions, but these send students off into a recruitment race that is predominantly based on impersonal applications and increasingly sophisticated interview processes (Chiavacci 2005), without a commitment made by employers to recruit a certain number of students annually. Responsibility for outcomes is thus increasingly individualized. Yet institutions still matter in another sense, for graduating from an elite university seems to now be more important than ever for securing a stable job at a large firm (Kariya 2011).

• The institutionalized school-to-work system nevertheless remains highly relevant to those interested in youth unemployment and joblessness in Japan. As Brinton (2011) has so insightfully shown, it is the uneven erosion of this system – whereby industrial high schools, in particular, remain wellconnected to companies, but where low-ranking general schools are all but cut off from such all-important recruitment networks – that may best explain the ‘production’ of workless youth in today’s Japan (Brinton 2011:138–43). We shall revisit Brinton’s findings in the final chapter of this book.

• Crucial continuities. While a lot has thus changed in the youth labour markets, the organization of work and the school-to-work transition system, certain continuities remain important. By far the most important of these is the practice of ‘periodic mass recruitment’ (part and parcel of the legacy of school-mediated transitions) that persists as an essential component of youth transitions despite tremendous tensions. As one consequence, university students longing to secure stable jobs face enormous pressures to do so during their third and fourth years, lest they miss for good the opportunity to enter a company under a fresh graduate (shin-sotsu) scheme that comes with the best career advancement prospects, stability and full occupational training (see Kariya and Honda, 2010 for a state-of-the art analysis of job-hunting issues). For those who fail, it remains extremely difficult to enter the core workforce at a later stage, producing a strong sense that young people in Japan enjoy few ‘second chances’. Because of such an institutional continuity – a key mechanism of labour market exclusion and marginalization – the post-industrial employment dilemma has taken on a particularly cruel edge in Japan (though labour market dualization, on the whole, seems to be deepening elsewhere also; see Emmenegger et al. 2012). As Esping-Andersen rightly points out, all other issues aside, it makes a world of difference for a person whether he/she is channeled into a ‘dead-end’ job that is literally just that – an end to good career prospects – or into one that is a stepping-stone to something more rewarding (Esping-Andersen 1996; also see Arnett 2004 on the role of transitional jobs during what he calls the emerging adulthood life-stage in the US).

Figure 1.3 Youth unemployment trends in Japan (1970–2010), %

Source: Statistics Bureau (www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/longtime/03roudou.htm#hyo_2); long-term time series data, Table 3.4; accessed 22 January 2011

Figure 1.4 Trends in irregular employment among Japanese youth as a share of total employment (1990–2010), %

Source: Statistics Bureau (www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/longtime/03roudou.htm#hyo_2); long-term time series data, table 10; accessed 22 January 2011

How to interpret these changes?

This speedy review of the emergence of the post-industrial youth employment dilemma in Japan, marked by higher unemployment and le...