1 Economic transition and institutional change in Central Asia

Joachim Ahrens and Herman W. Hoen

1 The aim of the book

This book seeks to explore the political-economic transitions in Central Asia and addresses the processes of economic reform, development and political change. Central Asian countries have received increasing attention from the international community, policymakers, foreign investors, and academics during the last decade. Owing to its rich resource endowments, the region has become important for advanced industrial countries as well as emerging economies. In addition, thanks to its geographical location between Russia and China, Europe and the Far East as well as in close neighbourhood to fragile states and threatened regimes such as Afghanistan and Pakistan, Central Asia has gained strategic importance for the international community.

The primary focus of this volume is on the importance of institutions and institutional change for economic performance and social change. Following North (1990), institutions are conceived as formal and informal rules including effective enforcement characteristics. Political, economic, and social institutions establish incentives for individual actors and organizations to make distinct decisions. Institutions thus provide a framework which constrains actors’ ability to act. This implies that the transition towards a market-oriented economy entails much more than a decentralization of decision making. Old market-impeding institutions need to be eliminated, and new market-enhancing institutions need to come into existence. Since institutions do not only exhibit economizing but also redistributive functions, the process of institutional change is usually not efficient. It is rather subject to hysteresis effects and path dependence, and institutional change, especially in times of systemic transformation, is frequently driven by the interests of those who are in power. This entails that the impact of political institutions and actors for economic reform and performance needs to be explicitly addressed. Similarly, this holds for international relations, institutions, and actors and their impact on economic performance in Central Asia.1

From the perspective of this book, Central Asia includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. These five Central Asian transition countries CATC(5) are all landlocked and most of them are well endowed with natural resources. After the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union, they declared independence in 1991 (Åslund 2007: 23). In terms of territory, Kazakhstan is by far the biggest country. It is twice as big as the four other republics put together and is roughly half the size of Europe. It has a population of 15 million inhabitants. Kazakhstan became a Soviet republic in 1936, and during the 1950s and 1960s many Soviet citizens were encouraged to help cultivate Kazakhstan’s northern pastures. The influx of mostly Russian immigrants skewed the ethnic mixture (Pomfret 2006: 43). After 1991, many Russians, most of them well skilled and educated, left the country (Jeffries 2003: 180–3). The country’s vast natural resources helped Kazakh authorities to maintain political stability of the country (Pomfret 2006: 56).

Kyrgyzstan is a relatively small country and has a population of five million. It is an extremely mountainous country, which hampers large-scale industrialization. There have been a number of political upheavals and ethnic conflicts since the country’s independence, most recently in spring and summer of 2010, but contrary to many of the other Central Asian republics, Kyrgyzstan had been praised for its rather liberal climate (Jeffries 2003).

The liberal claim does not hold for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan (Spechler 2008; Repkine 2004). These two countries are often presented as dismal states in which bad governance and corruption prevail (Spechler 2008). Turkmenistan borders the Caspian Sea and is extremely well endowed with natural resources. It had an extremely autocratic state with a president for life, Saparmurat Niyazov. Calling himself ‘Turkmenbashi’ (i.e. ‘father of all Turkmen’), he forced the population to adore him. In 2006, he died and was succeeded by Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov. So far, however, the forced adoration of the president has not softened.

The international reputation of Uzbekistan is somewhat better, but still far from first rate (Pomfret 2006: 27–8). With nearly 28 million people it is the most populous country in the region, followed by Kazakhstan, which has a much larger territory. During the Soviet era, Uzbekistan was intensively used for the production of cotton, the so-called ‘white gold’. This had devastating environmental consequences, among which the shrinkage of the Aral Sea is best known. The economy is desperately in need of a diversification of production structures, and from a political point of view the current concerns include terrorism by Islamic militants and the curtailment of human rights.

Tajikistan is the most tragic case of the CATC(5). After independence in 1991, it suffered a civil war. The death toll of the poorest successor country of the Soviet Union was estimated at between 30,000 and 60,000 (Jeffries 2003: 27). In the fight between government troops and opposing Islamic forces, the Tajik government was supported by Russian soldiers. In December 1996, a peace accord was signed, after which the transition to a market economy embedded in a more democratic order for the seven million Tajik was yet to begin (Pomfret 2006: 63–5).

This introductory chapter follows a twofold plan. First, it presents a bird’s eye view of transition processes in Central Asia and indicates major differences in economic performance. Second, it delineates a theoretical framework of analysis that enables readers to better understand the strategies, policies and developments in Central Asia. The outline of the chapter is as follows: the next section signifies why Central Asia can be perceived as a new and interesting field of area studies on economic transition and emerging markets. The subsequent section presents a general overview of the economic performance of Central Asian countries after the collapse of the system of central planning. The two decades of transition reveal remarkable differences in economic performance, which demand further exploration. The chapter continues with a section on the theoretical underpinnings of economic transition and explains the shift from neo-liberal approaches to concepts that include path dependency, institutional change, and, consequently a focus on the quality of governance. The last section presents an outline of the book.

2 Central Asia as a field of area studies on economic transition

After the fall of communism, the number of publications addressing issues of economic and systemic transition grew vastly. Many publishers of scientific books and journals arranged special series on the topic. Many publications were dominated by contributions of regional specialists and scholars, who had worked in the field of comparative economic studies until 1989. In addition, numerous scholars who had never previously revealed any particular interest in Central and Eastern Europe and the successor states of the Soviet Union shifted their academic attention to this new area of market transition (Csaba 1993). Thus, for many economists and political scientists, the transition dilemma created an excellent opportunity for applying empirical research, which had been obsolete during communism, if applicable at all.

But transition economics entailed more than the application of a well-known methodology in a new laboratory. There was also a need for theoretical reflection on, and a quest for theoretical explanation of, systemic change (Roland 2002; van Brabant 1998; Wagener 1993 and 1994). The phrase ‘transition towards a market economy’ has been usually restricted to the countries that had belonged to the Soviet bloc. While many countries have striven to implement a market economy, including less developed countries, transition economics focused on a designed shift from a communist to a capitalist order. Transition economists intended to address this system switch and that fact obliged them to look at the decay of communism and the climate of rivalry between the coordinating mechanisms of the two systems. Thus transition economics was partly an offspring of the study of comparative economic systems and partly a new field of research for mainstream economists, initially and primarily addressing issues of stabilization, liberalization, and privatization (Hoen 1996; Lavigne 1999).

The five Central Asian successor states of the Soviet Union have received much less attention by transition economists than, e.g. countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) or Russia, although they have exhibited all characteristics of transition societies. In addition, the region distinguishes itself by at least four other characteristics: First, Central Asia is extremely well endowed. The proven stocks of oil, gas, and other natural resources can be perceived as a special legacy that makes this region distinct from other transition countries. This peculiar legacy has a major impact on the opportunities for domestic paths of transition. Second, the countries’ endowments give the region an important geo-political position. Exports of natural resources such as gas and oil are becoming an important tool to gain political influence in the world. Third, all countries are landlocked and far away from major international markets, but they may gain an economic importance as transit countries. Fourth and in contrast to most other transition countries, the CATC(5) are non-democracies (or in the case of Kyrgyzstan a defective democracy). Credible commitments to establish liberal democracies do not exist and are not expected. All these characteristics have shaped and will continue to affect economic performance and provide (dis-) incentives for conducting further market-oriented and political reforms. To sum up, it is valid to perceive the region of Central Asia as a particular field of area studies that reminds observers of the Great Game. Just as in the nineteenth century the British and the Russians used the term Great Game for the strategic rivalry and the endeavour for supremacy in Central Asia, the region has again attracted rival interests of great powers, including Russia, China and the USA as well as the European Union; in addition, it is also subject to regional rivalries between national leaders within Central Asia.

3 Economic performance of Central Asia

Economic conditions differ widely among the CATC(5). Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are the poorest countries in the region. Welfare levels in Uzbekistan are somewhat higher, but since the exports of the white gold have been declining, the country has faced many problems (Pomfret 2006: 120–1). Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are well-endowed countries. Kazakhstan has an abundant supply of accessible mineral and fossil fuel resources. The development of petroleum, natural gas, and mineral extraction has attracted most of the over $40 billion in foreign investment in Kazakhstan since 1993 and accounts for some 57 per cent of the nation’s industrial output (or approximately 13 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP)) (EBRD 2011). According to some estimates, Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium, chromium, lead, and zinc reserves, the third largest manganese reserves, and the fifth largest copper reserves, and ranks in the top ten for coal, iron, and gold. It is also an exporter of diamonds and potassium.

Perhaps most significant for economic development, Kazakhstan currently has the eleventh largest proven reserves of both oil and natural gas (Pomfret 2006: 50–2). Turkmenistan is similarly endowed. Its economy is dominated by the gas industry, which accounts for almost half of its GDP. A major problem, though, is how its gas reserves, which are the fourth largest in the world, can be made accessible to the outside world (Repkine 2004: 160–4).

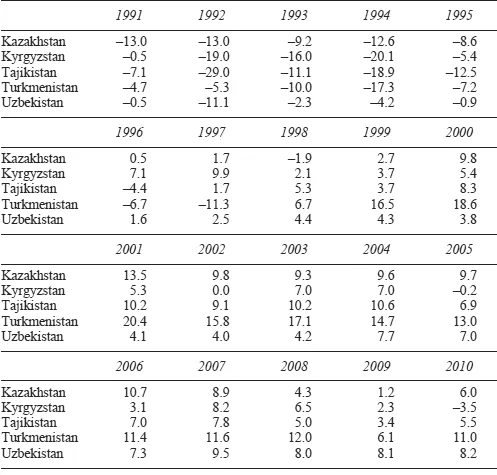

In the 1990s, all five Central Asian countries suffered in terms of falls in GDP (Table 1.1). Kazakhstan was the first country that experienced a heavy decline in production, but in comparison to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan the decline was still relatively modest. Turkmenistan followed a similar path to Kazakhstan, be it that the decline and recovery in the 1990s was followed with a time lag. In the first decade following the collapse of communism, Uzbekistan was the best performing country in Central Asia (Pomfret 2000; Zettelmeyer 1999).

At the end of the 1990s, the CATC(5) began to recover from the downturn. A slightly different picture emerged regarding the relative performance of these countries. Despite the fact that one should be cautious about statistics gathered in these countries (Pomfret 2006: 107–20), it is beyond any doubt that Turkmenistan has been the best-performing country in terms of economic growth over the last two decades (Repkine 2004). It has more than doubled its GDP since 1989, and it has had astonishing growth rates in a sequence of years since 1999. To a lesser extent that also holds for Uzbekistan. Its GDP level is now at 150 per cent of the level of 1989. Kazakhstan had a similar overall performance as Uzbekistan, albeit that its growth rates were a little more moderate. In 2008, it was at nearly 140 per cent of the GDP level of 1989. Kyrgyzstan and especially Tajikistan have been poorly performing over the two decades (Umarov and Repkine 2004: 202; Mogilevsky and Hasanov 2004: 226). In this period, the latter lost nearly half of its economic activity. Kyrgyzstan performed slightly better, but is not at the 1989 level of economic activity yet.

Table 1.1 GDP growth in Central Asia, 1991–2010 (in percentages)

Source: EBRD, Transition Report, various years.

4 Theoretical footholds for studying economic transition in Central Asia

During the 20 years since the fall of communism, there have been numerous controversies with respect to several crucial questions about systemic transition.2 First of all, the nature and direction of transition has been disputable. Second, disputes existed regarding the components of economic transition strategies, with respect to timing, pacing, and sequencing reform measures, and last, but not least, regarding the question whether or not economic transition can be subject to a constructivist approach and which actors would prove to become key drivers of economic restructuring and growth processes. The quest for effective economic strategies has been even aggravated because a general theory of economic transition has not been available.

In most transition countries, systemic change confronted policymakers and citizens with a problem of simultaneity:

• the transition of a formerly centrally planned economic system into a market-based order;

• the substitution of a liberal democracy for a communist dictatorship;

• establishing a state that rests on the rule of law and provides individuals with legal protection;

• creating a public bureaucracy which serves, not elites, but citizens and the public interest;

• citizens’ adaptation of democratic and market-oriented codes of behaviour.

In several countries, this transition-specific problem of simultaneity has been made even more complicated by...