![]()

Chapter 1

Positioning the woman judge

The youngsters believe that we come from a narrow background – it’s all nonsense – they get it from that man Griffith.

(Lord Denning)1

Despite general acceptance of judicial diversity as an almost unqualified ‘good thing’, the common perception of the judge as a ‘white man, probably educated at public school and Oxbridge’ remains largely accurate.2 As will become clear over the course of the next three chapters, debates abound as to why we have not got a diverse judiciary, whether we might want one, and how and when we might get one. But just how un-diverse is the judiciary in England and Wales, and how does the position of women, in particular, compare to men in judiciaries worldwide? And if, as appears to be the case, the judiciary is ‘pale and male’, and is likely to be for some time yet, should we be concerned? Why is diversity something we want to see in our judiciary?

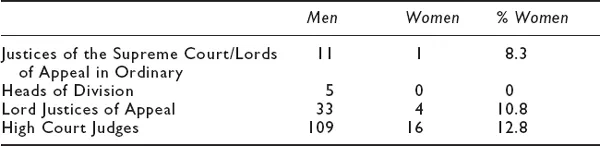

A pen portrait of the judiciary of England and Wales

According to Judicial Office statistics, as of January 2012, there are 3,792 judges in the judiciary in England and Wales, just over 824 of whom are women.3 In the senior judiciary, that is the High Court and above, there are just 21 women judges, representing 11.7 per cent of the Bench at this level. As can be seen from Table 1.1, the figures are stark. Lady Hale, the UK’s first and last woman Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, is the only woman on the Supreme Court bench. She has sat alone alongside her male colleagues since 2004, during which time nine further appointments have been made.4 When it comes to administrative and leadership positions within the senior judiciary, women fare even worse. Only one woman has ever held one of these positions – Lady Justice Butler-Sloss who was the first woman appointed to the Court of Appeal in 1988 and who was President of the Family Division between 1999–2005. Since her retirement none of the senior judges – that is the Lord Chief Justice, Master of the Rolls, President of the Supreme Court (the Senior Law Lord as was), Deputy President or any of the Heads of Division – has been a woman.5 The fact that there has not yet been a second woman judge in either the Supreme Court or as a Head of Division (and that we are still waiting for a woman Lord Chief Justice) underlines Albie Sachs’s view that the very ‘lists of female “firsts” … are reminders of continuing male domination rather than signs of female advancement’.6 In a similar vein, it is worth noting that, although there are now four women in the Court of Appeal, this is an increase of just one in six years. In fact, just one more woman sits in the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal or as a Head of Division combined, than was the case almost a decade ago.7 Between 1 October 2000 and 1 October 2011, only one of the 17 appointments (5.9 per cent) from the Court of Appeal to the position of Lord Chief Justice, Head of Division or the Supreme Court has been a woman.

Table 1.1 Members of the senior judiciary in England and Wales by gender in 2012

Source: Judiciary of England and Wales website.

There has been slightly more progress in the High Court where there are now 16 women judges (around 13 per cent). Perhaps unsurprisingly, women are better represented in the Family Division where they make up around 33 per cent, compared to 12 per cent of the Queen’s Bench Division and just 5.9 per cent of the Chancery Division. This is important. There are almost twice as many Chancery judges than Family judges in the current Court of Appeal, despite the Divisions being of similar size, suggesting that judges stand a greater chance of promotion from the Chancery Division.8 What this means is that, although the presence of women judges has increased in the pool as a whole, their chances of being appointed to the Court of Appeal have not improved at the same rate.

Of course, it is important not to treat the judiciary of England and Wales as a wholly homogeneous entity. There are clear differences in its demographic profile between the various levels of the judiciary. As one might expect, the position of women is better lower down the judicial ranks. Just under 30 per cent of all circuit and district judges are women, although this decreases slightly to 26 per cent once part-time positions are excluded. However, within this there is significant regional variation. For example, just four women serve as circuit or district (county court) judges in Wales, alongside 53 men.9 Women also tend to be better represented in the part-time judiciary. In 2010, around 16.5 per cent of recorders and 32.9 per cent of deputy district judges in the county courts were women.10

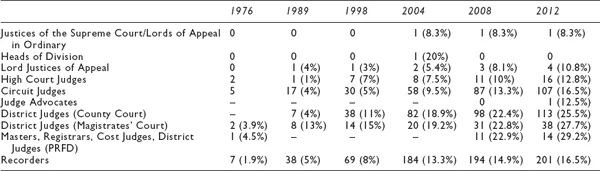

Clearly these statistics can only tell us so much. As Kate Malleson has noted, the rise in the number of women entering the judiciary coincided with a significant period of growth in the judiciary as a whole. Between 1970–2000 the judiciary grew tenfold to just over 3,000.11 This means that, at least in relation to some posts, although there has been an increase in the number of women appointed, the statistical impact of them joining the Bench has been modest. For example, although the number of women Recorders almost tripled in the 10 year period between 1998–2008 (from 69 to 201), the proportional representation of women at this level merely doubled from 8 per cent to 16.3 per cent. Nevertheless, while it is clear that the representation of women particularly in the senior judiciary remains low, there has been progress. The number, and proportional representation, of women in the Court of Appeal, High Court and circuit bench has more than tripled since the late 1980s. Overall, while changes to judicial posts make a direct comparison difficult, the number of women in the judiciary as a whole has risen from 4.6 per cent in 1989 to 21.7 per cent in 2012, decreasing to 3 per cent and 18.9 per cent respectively among the full-time judiciary.12

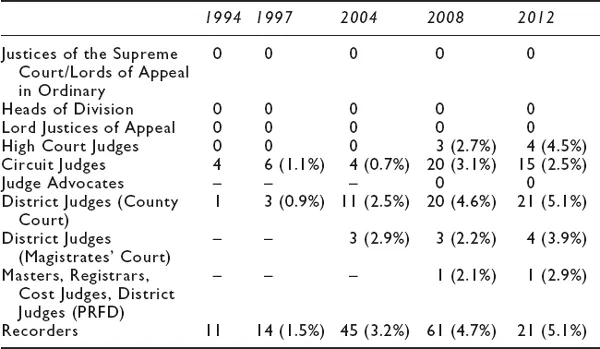

While there has been some increase in the number of women judges, as we can see from Table 1.3, judges from a black or minority ethnic background (BME) fare even worse.13 BME judges comprise just 2.8 per cent of the senior judiciary and 4.1 per cent of the judiciary as a whole.14 Mrs Justice Dobbs’s hope that her appointment to the High Court in 2004 ‘would be the first of many’ has not yet been realised.15 She is one of just four BME judges in the High Court, and was the only visible BME judge until Mr Justice Singh’s appointment in October 2011. She continues to be the only female BME judge in the senior judiciary. There are no BME judges of either sex in the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court. On current figures, Baroness Scotland’s prediction in 2009 that we will have to wait another 10–20 years for a black Supreme Court Justice seems about right.16 As with women judges, there are more BME judges in the lower courts and part-time judiciary. The number of BME Recorders, for example, has leapt from eight in 1992 and 14 in 1998 to 61 in 2012 (representing 6.5 per cent of the whole), and just over 10 per cent of tribunal judicial office-holders and 8 per cent of magistrates are from a BME group.

Table 1.2 Women members of the salaried judiciary and recorders in England and Wales, 1976–2012

Sources: Sachs and Wilson, Sexism and the Law, p. 175 (1976 figures); McGlynn, The Woman Lawyer, p. 173 (1989, 1998 figures); Judiciary of England and Wales website (2004, 2008, 2012 figures).

Table 1.3 BME members of the salaried judiciary and recorders in England and Wales, 1994–2012

Sources: McGlynn, The Woman Lawyer, p. 174 (1994, 1997 figures); Judiciary of England and Wales website (2004, 2008, 2012 figures).

Note: Mrs Justice Dobbs was the first judge from a BME background to be appointed to the High Court in October 2004.

However, here too, these increases have not been accompanied by comparable increases in proportional representation. Although there are now over three times as many BME circuit judges their proportional representation has risen by just one per cent. Interestingly, even though the number of male BME judges is more than double that of women, women tend to be better represented among BME judges. While the number of male judges (of all backgrounds) exceeds that of women judges by 4.5:1, among BME judges this decreases to around 3.8:1. In 2010, 5.9 per cent of women circuit judges had a BME background, compared to 2.1 per cent of male circuit judges.17 This was also the case in 2001 where, although BME judges represented just 1.1 per cent of the circuit bench (six judges), of the 44 female circuit judges two (4.5 per cent) had a BME background.

The judiciary also lacks diversity in terms of the professional background of the judges. Despite representing just 10 per cent of the legal profession, barristers make up 62.4 per cent of the judiciary, and 98.8 per cent of the senior judiciary.18 Moreover, as Table 1.4 shows, this domination is growing. In 2000, 13.5 per cent of the circuit bench were previously solicitors,19 compared to 12.5 per cent in 2011. Similarly, the number of solicitors becoming recorders has dramatically decreased in recent years. In 2000, 11.2 per cent of recorders were solicitors compared to just 5.2 per cent in 2011. This will have a knock on effect on the representation of solicitors in the High Court (currently 0.9 per cent) as appointees are typically recorders prior to appointment. Again, solicitors are better represented among women judges. In 2010, just under 14 per cent of women circuit judges were former solicitors, compared to 11.4 per cent of men. And, the percentage representation of solicitors among women recorders is almost double that of men.

This is where official statistics on judicial diversity end. The ‘Diversity Statistics’, posted on the Judiciary of England and Wales website, focus exclusively on sex, ethnicity and professional background as the key indicators of diversity. This is problematic. In particular, as Leslie Moran has argued in the context of discussion about the visibility of sexual orientation in debates about judicial diversity, the absence of such data in relation to certain characteristics is often given as a reason for not recognising, and therefore not addressing, their absence on the Bench.20 In other words, statistical invisibility promotes and reinforces the real-life invisibility of, or at least strategically hidden, identity characteristics on the Bench.21 Moreover, the lack of transparency and inconsistencies, as well as ‘gaps’ in the data currently collected and published make it difficult to track the progress of diversity or to draw comparisons across categories. In July 2011, the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) announced that it was to...