eBook - ePub

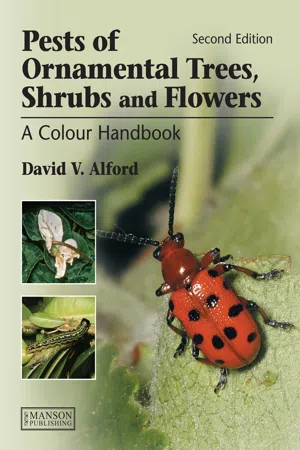

Pests of Ornamental Trees, Shrubs and Flowers

A Colour Handbook, Second Edition

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers have always been extremely popular and there is large demand-whether in gardens or parks-for alpines, bedding plants, cacti, cut flowers, house plants and pot plants, as well as herbaceous plants, ornamental grasses, shrubs and trees. The first edition of this comprehensive and beautifully illustrated book was e

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pests of Ornamental Trees, Shrubs and Flowers by David V Alford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Introduction

Ornamental plants are attacked by a wide range of pests, most of which are arthropods (phylum Arthropoda). Arthropods are a major group of invertebrate animals, characterized by their hard exoskeleton or body shell, segmented bodies and jointed limbs. Insects and, to a lesser extent, mites are of greatest significance as pests of cultivated plants.

Insects

Insects differ from other arthropods in possessing just three pairs of legs, usually one or two pairs of wings (all winged invertebrates are insects), and by having the body divided into three distinct regions: head, thorax and abdomen.

The outer skin or integument of an insect is known as the cuticle. It forms a non-cellular, waterproof layer over the body, and is composed of chitin and protein, the precise chemical composition and thickness determining its hardness and rigidity. The cuticle has three layers (epicuticle, exocuticle and endocuticle) and is secreted by an inner lining of cells which forms the hypodermis or basement membrane. When first produced the cuticle is elastic and flexible, but soon after deposition it usually undergoes a period of hardening or sclerotization and becomes darkened by the addition of a chemical called melanin. The adult cuticle is not replaceable, except in certain primitive insects. However, at intervals during the growth of the immature stages, the ‘old’ hardened cuticle becomes too tight and is replaced by a new, initially expandable one secreted from below. Certain insecticides have been developed that are capable of disrupting chitin deposition. Although ineffective against adults, they kill insects undergoing ecdysis (i.e. those moulting from one growth stage to the next).

The insect cuticle is often thrown into ridges and depressions, is frequently sculptured or distinctly coloured, and may bear a variety of spines and hairs. In larvae, body hairs often arise from hardened, spot-like pinacula (often called tubercles) or larger, wart-like verrucae. In some groups, features of the adult cuticle (such as colour, sculpturing and texture) are of considerable value for distinguishing between species.

The basic body segment of an insect is divided into four sectors (a dorsal tergum, a ventral sternum and two lateral pleurons) which often form horny, chitinized plates called sclerites. These may give the body an armour-like appearance, and are either fused rigidly together or joined by soft, flexible, chitinized membranes to allow for body movement. Segmental appendages, such as legs, are developed as outgrowths from the pleurons.

The head is composed of six fused body segments, and carries a pair of sensory antennae, eyes and mouthparts. The form of an insect antenna varies considerably, the number of antennal segments (strictly speaking these are not segments) ranging from one to more than a hundred. The basal segment is called the scape and is often distinctly longer than the rest; the second segment is the pedicel and from this arises the many-segmented flagellum. In geniculate antennae, the pedicel acts as the articulating joint between the elongated scape and the flagellum; such antennae are characteristic of certain weevils, bees and wasps. Many insects possess two compound eyes, each composed of several thousand facets, and three simple eyes called ocelli, the latter usually forming a triangle at the top of the head. Compound eyes are large, and particularly well developed in predatory insects, where good vision is important. The compound eye provides a mosaic, rather than a clear picture, but is well able to detect movement. The ocelli are optically simple and lack a focusing mechanism. They are concerned mainly with registering light intensity, enabling the insect to distinguish between light and shade. Unlike insect nymphs, insect larvae lack compound eyes but they often possess several ocelli, arranged in clusters on each side of the head. Insect mouthparts are derived from several modified, paired segmental appendages; they range from simple biting jaws (mandibles) to complex structures for piercing, sucking or lapping. Among phytophagous insects, biting mouthparts are found in adult and immature grasshoppers, locusts, earwigs, beetles etc., but may be restricted to the larval stages, as in butterflies, moths and sawflies. Some insects (e.g. various dipterous larvae) have rasping mouthparts which are used to tear plant tissue, the food material then being ingested in a semi-liquid state. Style-like, suctorial mouthparts are characteristic of aphids, mirids, psyllids and other bugs; such insects may introduce toxic saliva into plants and cause distortion or galling of tissue. Certain insects (notably some aphids) carry and transmit virus diseases to host plants.

The thorax has three segments – prothorax, mesothorax and metathorax – whose relative sizes vary from one insect group to the next. In crickets, cockroaches and beetles, for example, the prothorax is the largest section and is covered on its upper surface by an expanded dorsal sclerite called the pronotum; in flies, the mesothorax is greatly enlarged, and the prothoracic and metathoracic segments are much reduced. Typically, each thoracic segment bears a pair of jointed legs. Their form varies considerably but all legs have the same basic structure. Wings, when present, arise from the mesothorax and metathorax as a pair of fore wings and hind wings, respectively. In many insects the base of each fore wing is covered by a scale-like lobe, known as the tegula. Basically, each wing is an expanded membrane-like structure supported by a series of hardened veins, but considerable modification has taken place in the various insect groups. In cockroaches, earwigs and beetles, for instance, the fore wings have become hardened and thickened protective flaps, called elytra, and only the hind wings are used for flying; in true flies, the fore wings retain their propulsive function but the hind wings have become greatly reduced in size and are modified into drumstick-like balancing organs known as halteres. Wing structure is of importance in the classification of insects, and the names of many insect orders are based upon it. Wing venation is also of considerable significance.

The abdomen is normally formed from 10 or 11 segments, but fusion and apparent reduction of the most anterior or posterior segments are common. Although present in many larvae, abdominal appendages are wanting on most segments of adults, their ambulatory function, as found in various other arthropods, having been lost. However, appendages on the eighth and ninth segments remain to form the genitalia, including the male claspers and female ovipositor. In many groups, cerci are formed from a pair of appendages on the last body segment. These are particularly long and noticeable in primitive insects, but are absent in the most advanced groups. Abdominal sclerites are limited to a series of dorsal tergites and a set of ventral sternites; these give the abdomen a distinctly segmented appearance.

The body cavity of an insect extends into the appendages and is filled with a more or less colourless, blood-like fluid called haemolymph. This bathes all the internal organs and tissues, and is circulated by muscular action of the body and by a primitive, tube-like heart which extends mid-dorsally from the head to near the tip of the abdomen.

The brain is the main co-ordinating centre of the body. It fills much of the head and is intimately linked to the antennae, the compound eyes and the mouthparts. The brain gives rise to a central nerve cord which extends back mid-ventrally through the various thoracic and abdominal segments. The nerve cord is swollen at intervals into a series of ganglia, from which arise numerous lateral nerves. These ganglia control many nervous functions (such as movement of the body appendages) independent of the brain.

The gut or alimentary tract is a long, much modified tube stretching from the mouth to the anus. It is subdivided into three sections: a fore gut, with a long oesophagus and a bulbous crop; a mid-gut, where digestion of food and absorption of nutriment occurs; and a hind gut, concerned with water absorption, excretion and the storage of waste matter prior to its disposal. A large number of blind-ending, much convoluted Malpighian tubules arise from the junction between the mid-gut and the hind gut. These tubules collect waste products from within the body and pass them into the gut.

The respiratory system comprises a complex series of branching tubes (tracheae) and microscopic tubules (tracheoles) which ramify throughout the body in contact with the internal organs and tissues. This tracheal system opens to the outside through segmentally arranged valve-like breathing holes or spiracles, present along each side of the body. Air is forced through the spiracles by contraction and relaxation of the abdominal body muscles. Spiracles also occur in nymphs and larvae (they are often very obvious in butterfly and moth caterpillars) but they are often much reduced in number. In some groups (e.g. various fly larvae) the tracheae open via a pair of anterior spiracles, commonly located on the first body segment (prothorax), and a pair of posterior spiracles, usually located on the anal segment; these spiracles are often borne on raised processes. Morphological details of the spiracular openings and processes are often used to distinguish between species (as in agromyzid leaf miners).

Female insects possess a pair of ovaries, subdivided into several egg-forming filaments called ovarioles. The ovaries enter a median oviduct and this opens to the outside on the ninth abdominal segment. Many insects have a protrusible egg-laying tube, called an ovipositor. The male reproductive system includes a pair of testes and associated ducts which lead to a seminal vesicle in which sperm is stored prior to mating. The male genitalia may include chitinized structures, such as claspers which help to grasp the female during copulation. Examination of the male or female genitalia is often essential for distinguishing between closely related species.

Sexual reproduction is common in insects, but in certain groups fertilized eggs produce only female offspring and males are reared only from unfertilized ones. In other cases, male production may be wanting or extremely rare and parthenogenesis (reproduction without a sexual phase) is the rule.

Although some insects are viviparous (giving birth to active young), most lay eggs. A few, such as aphids, reproduce viviparously by parthenogenesis in spring and summer but may produce eggs in the autumn (after a sexual phase). Insect eggs have a waterproof shell. Many are capable of withstanding severe winter conditions on tree bark or shoots, and are the means whereby many insects survive from one year to the next.

Insects normally grow only during the period of pre-adult development, as nymphs or larvae, their outer cuticular skin being moulted and replaced between each successive growth stage or instar. The most primitive insects (subclass Apterygota) have wingless adults, and their eggs hatch into nymphs that are essentially similar to adults but smaller and sexually immature. The more advanced, winged or secondarily wingless, insects (subclass Pterygota) develop in one of two ways. In some, there is a succession of nymphal stages in which wings (when present in the adult) typically develop as external wing buds that become fully formed and functional once the adult stage is reached. In such insects, nymphs and adults are frequently of similar appearance (apart from wing buds or wings), and often share the same feeding habits. This type of development, in which metamorphosis is incomplete, is termed hemimetabolous. The most advanced insects show complete metamorphosis, development (termed holometabolous) including several larval instars of quite different structure and habit from the adult. Here, wings develop internally and the transformation from larval to adult form occurs during a quiescent, non-feeding pupal stage. Insect larvae are of various kinds. Some, commonly called caterpillars, have three pairs of jointed thoracic legs (true legs) and a number of fleshy, false legs (prolegs) on the abdomen. Many butterfly, moth and sawfly larvae are of this type. Unlike sawfly larvae, those of butterflies and moths are usually provided with small chitinous hooks known as crotchets. Some larvae, including many beetle grubs, possess well-developed thoracic legs but lack abdominal prolegs. In other insect larvae, legs are totally absent; fly and various wasp larvae are examples.

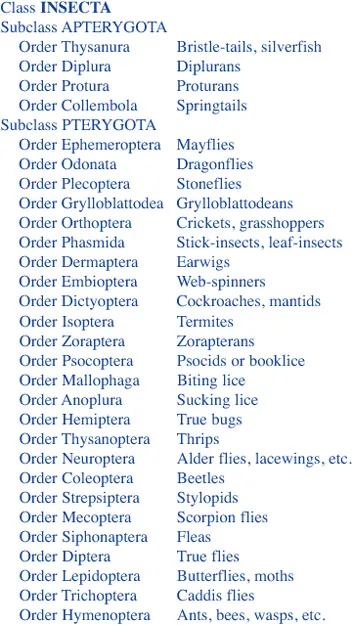

Classification of insects

Pests of ornamental plants are found in many different orders, the main groups being characterized as follows:

Collembola: small, wingless insects, often with a forked springing organ ventrally on the fourth abdominal segment; biting mouthparts; antennae usually with four segments; metamorphosis slight: family Sminthuridae (p. 20); family Onychiuridae (p. 20).

Orthoptera: medium-sized to large, stout-bodied insects with a large head, large pronotum and usually two pairs of wings, the thickened fore wings termed tegmina; fore wings or hind wings reduced or absent; femur of hind leg often modified for jumping; tarsi usually 3- or 4-segmented; chewing mouthparts; cerci usually short and unsegmented; development hemimetabolous, including egg and several nymphal stages: family Gryllotalpidae (p. 21); family Gryllidae (p. 21).

Dermaptera: elongate, omnivorous insects with biting mouthparts; fore wings modified into very short, leathery elytra; hind wings semicircular and membranous, with radial venation; anal cerci modified into pincers; development hemimetabolous, including egg and several nymphal stages: family Forficulidae (p. 22).

Dictyoptera: small to large, stout-bodied but rather flattened insects with a large pronotum and two pairs of wings, the thickened fore wings called tegmina; hind wings folded longitudinally like a fan; chewing mouthparts; antennae very long and thread-like; legs robust and spinose, and modified for running; tarsi usually 3- or 4-segmented; cerci many-segmented; development hemimetabolous, including egg and several nymphal stages: family Blattidae (p. 23).

Hemiptera: minute to large insects, usually with two pairs of wings and piercing, suctorial mouthparts; fore wings frequently partly or entirely hardened; development hemimetabolous, including egg and several nymphal stages (the egg stage often omitted).

Suborder Heteroptera: usually with two pairs of wings, the fore wings (termed hemelytra) with a horny basal area and a membranous tip; hind wings membranous; wings held flat over the abdomen when in repose; the beak-like mouthparts arise from the front of the head and are flexibly attached; prothorax large; some species are phytophagous but many are predacious: family Tingidae (p. 24); family Miridae (p. 26).

Suborder Auchenorrhyncha: wings (when present) typically held over the body in a sloping, roof like posture; fore wings (termed elytra) uniform throughout and horny; hind wings membranous; mouthparts arising from the base of the head and the point of attachment rigid; entirely phytophagous. Superfamily Cercopoidea – tegulae absent; hind legs modified for jumping, with long tibiae bearing one or two long spines: family Cercopidae (p. 28). Superfamily Fulgoroidea – elytra with anal vein Y-shaped; antennae 3-segmented: family Flatidae (p. 30). Superfamily Cicadelloidea – tegulae absent; hind legs modified for jumping, with long tibiae bearing longitudinal rows of short spines: family Cicadellidae (p. 31).

Suborder Sternorrhyncha: wings (when present) typically held over the body in a sloping, roof like posture; fore wings and hind wings membranous and uniform throughout; mouthparts arising from a rearward position relative to the head and the point of attachment rigid; entirely phytophagous. Superfamily Psylloidea – antennae usually 10-segmented; tarsi 2-segmented and with a pair of claws: family Psyllidae (p. 36); family Triozidae (p. 41); family Carsidaridae (p. 43); family Spondyliaspidae (p. 44). Superfamily Aleyrodoidea – antennae 7-segmented; wings opaque and coated in whitish wax: family Aleyrodidae (p. 45). Superfamily Aphidoidea – females winged or wingless; wings, when present, usually large and transparent, with few veins; abdomen often with a pair of siphunculi: family Aphididae (p. 49); family Adelgidae (p. 95); family Phylloxeridae (p. 100). Superfamily Coccoid...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Pests of Ornamental Trees, Shrubs and Flowers

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Insects

- Chapter 3 Mites

- Chapter 4 Miscellaneous Pests

- Glossary

- Selected Bibliography

- Host Plant Index

- General Index