eBook - ePub

The Material Word (Routledge Revivals)

Some theories of language and its limits

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Material Word (Routledge Revivals)

Some theories of language and its limits

About this book

First published in 1980, this reissue is a study of the sociology of language, which aims to bridge the gap between textbook and monograph by alternating chapters of explication and analysis. A chapter outlining a particular theory and suggesting general criticisms is followed by a chapter offering an original application of that theory. The aim of the authors is to treat text and talk as the site of specific practices which sustain or subvert particular relations between appearance and reality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Material Word (Routledge Revivals) by David Silverman,Brian Torode in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part I

Introduction: the language of mastery

The assumption, that speech is merely the appearance of an external reality to which it refers, is here reversed, in order to shift attention to speech as a reality in its own right. Analysis of everyday conversations shows that the reference of the word ‘I’ is not the unique individuality of the speaker who utters it, but the linguistic practices available to all speakers. These constitute its sense in contradictory ways.

chapter 1

Interrupting the ‘I’

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I, choose it to mean—neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be masterthat’s all.’

– Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking Glass (1873, p. 124).

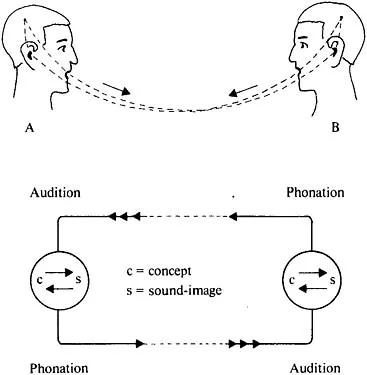

There is a schema which is so powerfully reiterated both in academic (written) and in commonsense (spoken) accounts of the linguistic situation that today it passes for that situation itself. According to the schema, linguistic communication consists in the transmission of immaterial ideas or concepts from one person (speaker or writer) to another (hearer or listener) by means of material signs such as marks on paper or vibrations of the air waves. Ferdinand de Saussure (1974, pp. 11–12) pictures the situation as shown in Figure 1.

When communication is interpreted in this way, the interplay of signs is not treated as a reality in its own right. Rather, the sign is taken as the signifier, indicator, or appearance of a signified essential reality which underlies it. For Saussure, this reality is the conceptual content which, he supposes, is somehow held in the brain of the communicating person.

The brain is unavailable to the researcher. Its content, conceptual or otherwise, remains mysterious, and can only be the subject of speculation or arbitrary assumption. The arbitrary and speculative mysticism attaching to the traditional interpretation of communication can be called, in a precise sense, idealism, in that it purports to treat the material sign as the mere appearance of an underlying ideal reality.

In opposition to the traditional interpretation our intention is materialist. We attempt to treat the interplay of material signs as a reality in its own right.

A curious feature of Saussure’s work is that while taking as its topic the interplay of material signs, it understands this topic always within the context of an essentialist and ideal reality supposedly underpinning these signs. Hence the first question which poses itself to our materialist project is how does the interplay of material signs give rise to essentialist conceptions of ideality? In our attempt to answer this question, Saussure’s text, which explicitly articulates and develops the traditional conception, is doubly valuable. First, it sets out in theory the workings of any linguistic communication via talk or text from one person to another. Second, it is itself a linguistic communication, and the way in which it works as a text in practice can be interrogated and compared to the theory. We refer to this interrogation, which reveals the gap between the theory and practice of the communication, as an interruption of the communication.1

Figure 1

Interpretation

Consider an interpretation of Saussure’s practice in terms of his own theory. His text, i.e. the diagram on p. 4, is to be regarded as an inscription of certain concepts in his own brain. In reading his text, we undertake a process of vision whereby his material signs are translated into concepts in our brains.

However, we can never be certain whether our concepts will correspond with his. To bring this correspondence into question is to interrupt Saussure’s practice in terms of his own theory. We know very little about the kind of thing the ‘concepts’ are. However if the effect of the diagram upon our brains is an example of these concepts, it is not clear why the concepts should differ significantly from the diagram itself. The situation is clarified if we turn our attention away from our experience of the concepts to our reading of his text.

Saussure seeks to give an account of communication and, in the first instance, speech, In order to give point to his account, he has to give point to that speech. The point of speaking, according to Saussure, is to attempt to bridge the gap between brains whose content is mutually unavailable. In order to satisfy this requirement, we are supposed to assume that the concepts corresponding to his diagram in our brains necessarily differ from the concepts which originated the diagram in his.

A number of results follow if we make this assumption. First, our own understanding of his theory will always differ from, and so be inferior to, his. He will always be privileged with regard to the understanding of his own writing, since it cannot reproduce his concepts. Second, and more generally, according to this theory language always fails in its objective because it does not succeed in communicating concepts. (If it did succeed there would be no need for further speech, or writing.) Third, given that language arises in order to solve an insoluble problem, it follows that there can never be any change in the linguistic situation: though Saussure’s concepts differ from ours, his signs (his diagrams) do not.

But if we shift attention from the conceptual contents of the brain to the material signs of language, then these results take on a new significance. The first implies that our writing in response to reading Saussure’s text must differ from his original writing; but since this is necessarily so there is no reason to deplore it. Instead we should simply acknowledge that language is always in change. The second implies that given the failure of language to correspond with or to communicate concepts, concepts are not the basis on which linguistic change should be understood. This, then, challenges the third implication. For if language is always in change, then we require a theory other than Saussure’s to explain it.

The practice of Saussure’s text transcends its stated theory, and out of this practice another theory can be built. Consider again the point of reading Saussure’s diagram, if the concepts which we attach to it as readers can never correspond to those he attached to it as writer. If the conceptual difference is the point, then we can only gaze in uncomprehending astonishment at this evidence of a brain different from our own. But what if this evidence, the material language, is of interest in its own right? (This could not be the case in Saussure’s own theory, since for him the signs must already be comprehensible for us to understand the text, in our limited way, at all.) In this case the point is that Saussure has assembled material signs in a way in which we ourselves had not assembled them before—but a way in which we could now assemble them. The point of reading Saussure’s text is now not the theory but the practice of language which is there exhibited.

More generally, we learn from an interruption of Saussure’s text that the point of communication is not the transmission from brain to brain of theoretical concepts, but the mutual learning by practitioners of linguistic practices. This learning, which we hope to have exemplified in reading a brief passage from Saussure, is not a passive reception of the signs communicated by one person to another, but involves an active struggle. In this struggle the signs communicated by the first person can be contrasted with the way in which they are communicated, so producing a new assembly of signs.

Interruption

Ultimately however the struggle is not between one person and another but rather between ways of speaking and writing. As is apparent even in this brief example from Saussure such struggle is already under way within the language of a single person. In this case, to interrupt it is simply to provoke tendencies at work in that first language. In this sense, the practice of interruption seeks not to impose a language of its own but to enter critically into existing linguistic configurations, and to re-open the closed structures into which they have ossified.

This ossification arises above all from the treatment of material signs as dependent for their sense upon reference to an external, immaterial, reality—including those cases where this reality is given the name of a material form. Thus, by long tradition, words derive their meaning from the ‘things’ to which they refer. From the more recent sociological viewpoint, speech is but the expression of relationships between speakers, conceived as ‘social facts’. In each case language is made the slave of an extra-linguistic master, either ‘natural’ or ‘social’ in character.2

The twentieth-century project has aimed to reverse this relation. Saussure, Wittgenstein and Garfinkel are united in their view of linguistic practices as a reality sui generis, constitutive of such sense as speakers and hearers can have of the natural and social worlds.

The traditional conception, which this project opposes, is manifestly essentialist in its assumption that man’s relations with nature and with society are unaffected by the language in which they are formulated. It neglects the fact that language is itself both ‘natural’ and ‘social’ in character, and so is an integral part of those relations. It wants to place language outside each of these realms and make it transparent.

But the modern project is equally essentialist. It acknowledges that the ‘natural’ and the ‘social’ interplay in the words which refer to them. But it treats this interplay as itself closed. In seeking to explicate the principles of thise closure, it makes language once again the slave of an extra-linguistic master, though paradoxically its name, Grammar, is that of language itself. It places language in a realm of its own, and makes it opaque.

An attempt will be made, in the pages which follow, to break with these formulations. As against the reductionist approaches which inspire research in the psychoanalysis of language on the one hand and sociolinguistics on the other, we insist that language must be treated as an object of enquiry in its own right.3 But as against the search for closed unity which inspires research in ethnomethodology and structuralism, we insist that languages are, in practice, plural and open.

To insist upon the plurality and openness of languages, as against the reductionist closure which is imposed upon language by the ways in which it is conventionally studied, is not an exercise in neutrality. It requires in our view a political intervention, because it reveals political choices which are already being made, by languages whose neutrality is conventionally asserted.

We refer to this intervention as an interruption of the neutrality of language, a neutrality which is primarily asserted by interpretation imposed upon language from the outside. In our usage, ‘interpretation’ refers to the practice of treating language as the mere ‘appearance’ of an extra-linguistic ‘reality’ pre-supposed by the interpretation. This practice is itself not what it appears to be: it does not do what it says. For it is impossible to formulate an extra-linguistic reality, e.g. ‘nature’, ‘society’, or ‘grammar’ except in language. Thus in pretending to uphold a non-linguistic and so neutral reality the interpretation in practice imposes its own language upon that of the language which it interprets.

As we attempt to show, interpretation is a very widespread practice of linguistic mastery, to be found not simply in analytic academic approaches to language, but also in everyday linguistic practice in such settings as schools, hospitals, and elsewhere. As we also try to show, the interruption of this mastery is also already in progress, not only within these settings but also in literary texts and within academic debates also. But since interpretation is allpervading and reasserts itself on every possible occasion, these instances are elusive and require an interruption of the conventional setting, text, and debate in order to discover them at all.

For us interruption is the attempt to reveal the interplay between ‘appearance’ and ‘reality’ within language itself. As against the view of language as a reality sui generis, whether transparent or opaque, we insist that language necessarily refers, as appearance, to a reality other than itself. But, we propose, the way in which it does this is to refer to other language. Thus plurality is inseparable from language, and it is the play of reference from one language to another language that suggests the reference of language to a reality other than language.

Irony and the ‘I’

What is involved in the distinctions so far drawn may be exemplified by considering some instances of speaking, taken from a study of conversations within a secondary school classroom, involving the word I. For the purposes of this exploration, the traditional view of language is well represented by the statement by Charles Sanders Peirce (quoted from Burks, 1949, pp. 677–8):

I, thou, that, this,…indicate things in the directest possible way. … A pronoun is an index.… A pronoun ought to be defined as a word which may indicate anything to which the first and second person have suitable real connections, by calling the attention of the second person to it.

Let us call realistic this view that such a word as I is meaningful first and foremost by its ‘real connections’ (which Peirce assumes to be present to hand in the situation in which the word is spoken). The meaning is thus the social or natural referent of the word.

The sociological variant of this traditional view is exemplified by the work of R. Brown and A. Gilman (1972, p. 265) on The pronouns of power and solidarity’. They point out that: ‘a historical study of the pronouns of address reveals a set of semantic and social psychological correspondencies.’ Brown and Gilman investigate historical and social variation in the use of second person pronouns to mark intimacy and distance, superordination and subordination. They interpret the meaning of pronouns as being the social norms to which, in their differential usage, they conform. Despite its different version of reality, this viewpoint is realistic in the same way as that of Peirce.

The modern view is represented by Harold Garfinkel and Harvey Sacks’s discussion of such terms as ‘“here, now, this, that, it, I, he, you, there, then, today, tomorrow” ‘which ‘have been called indicators, egocentric particulars, indexical expressions, occasional expressions, indices, shifters, pronomials, and token reflexives,’ (1970, p. 347): ‘We begin with the observation about these phenomena that everyone regularly treats such utterances as occasions for reparative practices [and] that such practices are native not only to research but to all users of the natural language.’ Garfinkel and Sacks would term the approach of Peirce or Brown and Gilman ‘natural’, the statement of a language unwilling to examine its own resources. As against this, ethnomethodologists propose an exploration of what is involved in the mastery of the practices of natural language.

In the light of these distinctions, consider the following conversation, taken from the observations of a school classroom by Torode:

Jones: ‘I got three pieces of tart for pudding.

Russell: Yeah, by starving the others.

Jones: They could never starve me.

Russell: Yeah, by starving the others.

Jones: They could never starve me.

At the risk of undue brevity, we propose that the ‘natural’ approach will observe what is non-obvious about Jones’s remark to be the breaking of a presumed norm, roughly of the form ‘one each’. Russell calls attention to this non-obviousness, and so establishes the point of Jones’s remark, by noting that given ‘one each’ as the norm, more for one implies less for others. This implies that the proper object of a natural sociology is the norm whose in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Part I: Introduction: the language of mastery

- Part II: The limits of language

- Part III: Language and thought

- Part IV: Language and society

- Part V: The practice of ordinary language

- Part VI: Language, sign and text

- Part VII: Conclusion: the mastery of language