![]()

Section IV

Social, Cultural, and Evolutionary Factors in Social Conflict and Aggression

![]()

15

The Male Warrior Hypothesis

Mark Van Vugt

VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Alien biologists collecting data about different life forms on Planet Earth would no doubt come up with contradictory claims about human nature. They would witness the human capacity to help complete strangers in sometimes large groups, yet they would also observe many incidents of extreme violence, especially between groups of males. To make sense of the data, the alien researchers would probably conclude that humans are a fiercely tribal social species. Some time ago, Charles Darwin speculated about the origins of human tribal nature: “A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection” (1871, p. 132). Unfortunately Darwin’s brilliant insight was ignored for more than a century by fellow scientists, yet it is now gaining impact. Here I offer an evolutionary perspective on the social psychology of intergroup conflict, offering new insights and evidence about the origins and manifestation of coalitional and intergroup aggression.1

Social scientists are increasingly adopting an evolutionary approach to develop novel hypotheses and to integrate data on various aspects of human social behavior (Buss, 2005; Van Vugt & Schaller, 2008). The evolutionary approach is based on the premise that the human brain is a product of evolution through natural selection in the same way our bodies are the products of natural selection. Evolutionaryminded psychologists further propose that the human brain is essentially social, comprising many functionalized mechanisms—or adaptations—to cope with the various challenges of group living (Van Vugt & Schaller, 2008). One such specialized mechanism is coalition formation. Forming alliances with other individuals confers considerable advantages in procuring and protecting reproductively relevant resources (e.g., food, territories, mates, offspring) especially in large and diverse social groups. Coalitional pressures may have led in human evolution to the emergence of some rather unique human traits such as language, theory of mind, culture, and warfare. It has been argued that ultimately the need to form ever larger coalitions spurred the increase in human social network size and led to a concomitant brain size to hold these networks together and to deal effectively with an intensified competition for resources—this has been dubbed the Machiavellian Intelligence hypothesis, the Social Brain hypothesis, or the Social Glue hypothesis (Byrne & Whiten, 1988; Dunbar; Van Vugt & Hart, 2004). According to these hypotheses, our social brain is therefore essentially a tribal brain.

In searching for the origins of the human tribal brain it is useful to make a distinction between proximate and ultimate causes. An act of intergroup aggression such as war, terrorism, gang-related violence or hooliganism could be explained at two different levels at least. First, why did this particular group decide to attack the other? This proximate question interests most sociologists, political scientists, historians, and social psychologists studying social conflict. Second, one could ask why humans have evolved the capacity to engage in intergroup aggression—this ultimate question interests mostly evolutionary-minded psychologists and anthropologists. Addressing questions at different levels produces a more complete picture, but these levels should not be confused (Buss, 2005; Van Vugt & Van Lange, 2006).

In terms of ultimate causes of intergroup aggression, three classes of explanations are generally invoked (Kurzban & Neuberg, 2005; Van Vugt, 2009; see also Chapters 10 and 18 in this volume). The first treats it as a by-product of an adaptive in-group psychology. Being a highly social and cooperative species, humans likely possess tendencies to favor helping members of in-groups (Brewer, 1979; Brewer & Caporael, 2006; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). As a result of this in-group favoritism, people show either indifference or (perhaps worse) a dislike for members of out-groups. An alternative by-product hypothesis views intergroup aggression as an extension of interpersonal aggression. The argument is that humans have evolved specialized mechanisms to engage in aggression against conspecifics and that these mechanisms have been co-opted to cope with a relatively novel evolutionary threat, namely, aggression between groups (Buss, 2005). The third class focuses explicitly on an adaptive inter-group psychology. The argument is that humans likely evolved specific psychological mechanisms to interact with members of out-groups because such situations posed a significant reproductive challenge for ancestral humans. This latter hypothesis accounts for the highly textured social psychology of intergroup relations and is therefore more persuasive. For instance, people do not have some hazy negative feeling toward an out-group; in some instances out-groups motivate a desire to approach or avoid and in other instances to fight, dominate, exploit, or exterminate.

Recent work on prejudice and intergroup relations recognizes this textured nature of intergroup psychology and has generated many new insights and empirical findings consistent with this view (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005; Kurzban & Leary, 2001; Schaller, Park, & Faulkner, 2003; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; Van Vugt, De Cremer, & Janssen, 2007; Van Vugt, 2009). Given the complexity of intergroup relations, there are probably many different adaptive responses pertaining to the nature and type of intergroup challenge. From an evolutionary perspective, it becomes clear that not all intergroup situations are equal because not all out-groups are equal. For instance, not all out-groups consist of coalitions of individuals who engage in coordinated action—think of the homeless, the elderly, or people with blue eyes. Humans are likely to have evolved coalition-detection mechanisms that are responsive to various indicators of tribal alliances (Kurzban, Tooby, and Cosmides, 2001). As Kurzban and Leary note, “Membership in a potentially cooperative group should activate a psychology of conflict and exploitation of out-group members—a feature that distinguishes adaptations for coalitional psychology from other cognitive systems” (p. 195). In modern environments, heuristic cues such as skin color, speech patterns, and linguistic labels—regardless of whether they actually signal tribal alliances—may engage these mechanisms (Kurzban et al.; Schaller et al.). Perhaps equally important, many other salient cues such as gender, age, or eye color may be far less likely to engage this tribal psychology. We should note that although this tribal psychology likely evolved in the evolutionary context of competition for resources (e.g., territories, food, and mates), this does not imply that it is contemporarily activated only within contexts involving actual intergroup conflict as proposed, for instance, by realistic conflict theory (Campbell, 1999).

The specific psychological reactions of individuals in intergroup contexts should further depend on whether one’s group is the aggressor. For the aggressors, desires to dominate and exploit—and the associated psychological tendencies— would be functional. For the defending party, desires to yield, to avoid, or to make peace, along with the associated psychological tendencies, would be functional. Of course, in many situations, a group’s position as being the dominant or subordinate party is transient or ambiguous so it is likely that the two psychological tendencies are activated in similar situations by similar cues and moderated by similar variables (social dominance theory; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999).

The Male Warrior Hypothesis

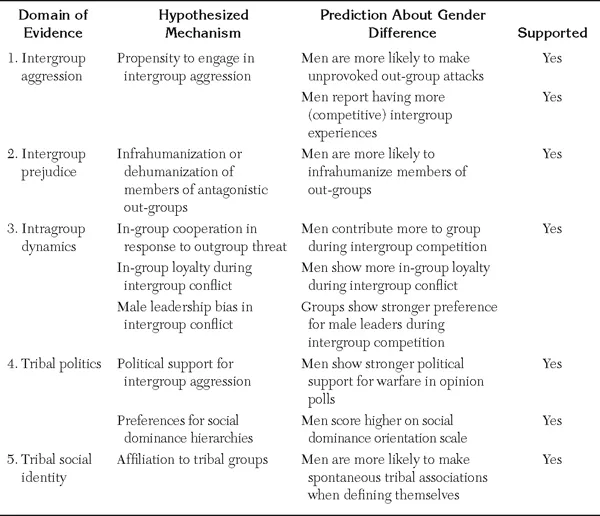

An important implication of this evolutionary tribal brain hypothesis is that inter-group conflict may have affected the psychologies of men and women differently. Intergroup conflict has historically involved rival coalitions of males fighting over scarce reproductive resources, and this is true for early humans as well as chimpanzees, our closest genetic relative (Chagnon, 1988; De Waal, 2006; Goodall, 1986). Men are by far the most likely perpetrators and victims of intergroup aggression, now and in the past. As a consequence, this aspect of coalitional psychology is likely to be more pronounced among men, which we dubbed the male warrior hypothesis (MWH, see Table 15.1; Van Vugt et al., 2007; Van Vugt, 2009). This hypothesis posits that due to a long history of male-to-male coalitional conflict men have evolved specialized cognitive mechanisms that enable them to form alliances with other men to plan, to initiate, to execute, and to emerge victorious in intergroup conflicts with the aim of acquiring or protecting reproductively relevant resources.

Table 15.1 The Male Warrior Hypothesis: Domains of Evidence, Hypothesized Mechanisms, Predictions, and Support For Gender Differences

Evolutionary Models

The MWH fits into a tradition of evolutionary hypotheses about gender differences in social behavior. There is already considerable evidence for gender differences in morphology, psychology, and behavior that are functionally related to different selection pressures operating on men and women throughout human, primate, and mammal evolution (Campbell, 1999; Eagly & Wood, 1999; Geary, 1998; Taylor et al., 2000). Due to a combination of differences in parental investment and parental certainty men and women pursue somewhat different mating strategies (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Trivers, 1972). In humans—as in most other mammals—mothers invest more heavily in their offspring; consequently, it will be physiologically and genetically costlier for women to be openly aggressive (Archer, 2000; Campbell, 1999; Taylor et al., 2000). Yet, as the less investing sex and under the right conditions, it can be attractive for men to form aggressive coalitions with the aim of acquiring and protecting valuable reproductive resources.

Tooby and Cosmides’s (1988) risk contract hypothesis specifies four conditions for the evolution of coalitional aggression, which underscores the evolutionary logic of the hypothesized gender differences in warrior psychology. First, the average long-term gains in reproductive success (i.e., mating opportunities) must be sufficiently large to outweigh the average costs (i.e., injury or death). Second, members of warfare coalitions must believe that their group is likely to emerge victorious in battle. Third, the risk that each member takes and the importance of each member’s contribution to victory must translate into a corresponding share of benefits (cf. the free-rider problem). Fourth, when individuals go into battle they must be cloaked in a “veil of ignorance” about who will live or die. Thus, if an intergroup victory produces, on average, a 20% increase in reproductive success, then as long as the risk of death for any individual coalition member is less than 20% (e.g., 1 in 10 die) such warrior traits could be selected for. This model assumes that the spoils of an intergroup victory are paid out in extra mating opportunities for the individual males involved, and thus it is essentially an individual selection model based on sexual selection.

Alternatively, a specific male warrior psychology could have evolved via group-level selection. Multilevel selection theory holds that if there is substantial variance in the reproductive success among groups then group selection becomes a genuine possibility (Wilson, Van Vugt, & O’Gorman, 2008). As Darwin (1871) noted, groups of selfless individuals do better than groups of selfish individuals. Although participating in intergroup conflict is personally costly—because of the risk of death or injury—genes underlying propensity to serve the group can be propagated if group-serving acts contribute to group survival. In a recent empirical test of this model, Choi and Bowles (2007) showed via computer simulations that altruistic traits can spread in populations as long as there is competition between groups and altruistic acts benefit in-group members and harm out-group members (parochial altruism).

One condition conducive to group-level selection occurs when the genetic interests of group members are aligned, such as in kin groups. In kin-bonded groups, individuals benefit not just from their own reproductive success but also from the success of their family members (inclusive fitness; Hamilton, 1964). Ancestral human groups are likely to have been based around male kin members, with females moving between groups to avoid inbreeding (so-called patrilocal groups). This offers a complementary reason for the evolution of male coalitional aggression: because the men are more heavily invested in their group, they have more to lose when the group ceases to exist. In addition, the collective action problem underlying coalitional aggression is less pronounced when group members’ genetic interests are aligned. Incidentally (but perhaps not coincidentally), the same patrilocal structure is found in chimpanzees: male chimpanzees also engage in coalitional aggression (Goodall, 1986; Wrangham & Peterson, 1996).

These evolutionary models do not preclude the possibility of cultural processes at work that could exacerbate or undermine male warrior instincts (Richerson & Boyd, 2005). In fact, many of the evolved propensities for coalitional aggression are likely to be translated into actual psychological and behavioral tendencies by socialization practices and cultural norms. Thus, it is entirely possible that in certain environments it could be advantageous for societies to suppress male warrior tendencies (so-called peaceful societies) or to turn females into dedicated warriors. A modern-day example of the latter is the state of Israel, which is involved in a continuous war with its Arab neighbors. To increase its military strength, Israel has a conscription army of both men and women and currently has the most liberal rules regarding the participation of females in actual warfare (Goldstein, 2003). We would expect the socialization practices among Israeli girls to match those of boys, potentially attenuating any innate psychological differences.

Evidence for the MWH From Across the Behavioral Sciences

Evidence for various aspects of this male warrior phenomenon can be found throughout the behavioral science literature, for instance, in anthropology, history, sociology, political science, biology, psychology, and primatology. As stated, across all cultures, almost any act of intergroup aggression is perpetrated by coalitions of males, for instance, in situations of warfare, genocide, rebellion, terrorism, street gangs, and hooligan violence (Goldstein, 2003; Livingstone Smith, 2007). Evidence of male-to-male coalitional aggression goes back as far as 200,000 years (e.g., mass graves containing mostly male skeletons with evidence of force; Keeley, 1996). Men are also the most likely victims of intergroup aggression. On average, male death rates due to warfare among hunter-gatherers are 13% (according to archaeological data) and 15% (according to ethnographic data; Bowles, 2006), suggesting a relatively strong selection pressure on male warrior traits. The figure is sometimes even higher. Among the Yanomamö in the Amazon Basin, an estimated 20–30% of adult males die through tribal violence (Chagnon, 1988), compared with less than 1% of the U.S. and European populations in the twentieth century. Finally, the primate literature reveals that, among chimpanzees, adult males form coalitions to engage in v...