1

Media and radicalisation

Grappling uncertainties in the new media ecology – radicalisation gone wild

As part of her evidence to the UK government appointed Iraq Inquiry,1 Baroness Eliza Manningham-Buller, Director General of MI5, 2002–2007, directly connected the UK’s role in the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003 to an increased threat of radicalisation in Britain. She stated:

This quote from Baroness Manningham-Buller’s recorded evidence was one of a number that soon appeared on news websites, and in the national UK press the following day. For instance, the above quote was exactly how it appeared (in inverted commas) contained within a story on page 7 of The Guardian of the 21 July 2010, under the title: ‘Iraq invasion radicalised British Muslims and raised terror threat, says ex-MI5 chief’ (Guardian 2010). However, applying a modified form of conversation analysis to the video recording of this extract from the Iraq Inquiry (Box 1.1, below) the emphases and texture of Baroness Manningham-Buller’s words and expressions can be illuminated:

Box 1.1 Modified conversation analysis transcript of the television recording of a short segment of Baroness Manningham-Buller’s evidence to the Iraq Inquiry (BBC News Channel, 20 July 2010)

Our involvement (0.5) in Iraq (1.0) erm (0.5) radicalised er for want of a better word

[part laughs]

but [inhales] erm (0.5) a whole generation (0.5) of young people (0.5) some of them

[sits back in seat]

British Citizens–not-a-whole-generation (0.3) a few

among a generation (0.5) e- who

[gesticulates with hands held outward]

were erm saw our involvement in (0.5) Iraq on top of our involvement in Afghanistan as being an attack on Islam.

The timed (approximate) pauses (indicated with the timing in brackets) show the highly reflective pace of Baroness Manningham-Buller’s talk. So, she can clearly be heard (and seen – she looked down for most of this part of her evidence rather than looking at the committee members arranged in a semi-circle before her) to be choosing her words very carefully. Her nervous-sounding qualification of her use of the term ‘radicalisation’ thus seems out-of-synch with her very purposefully chosen phrases, suggesting perhaps that this was a rehearsed ambiguity. In other words, the qualification of the term ‘radicalisation’ here is indicative of the term’s wider ambiguous or controversial status.

The slipperiness of the application of the term radicalisation and the scaling of the threat it posed is also indicated by what appears at least to be a genuine (or that might even have been a rehearsed) slip (indicated by the Baroness sitting back in her seat and gesticulating as she tries to find the right qualification to her words). The correction of ‘a few among a generation’ after the suggestion that ‘a whole generation of young people’ had been radicalised by the UK’s military involvement in Iraq, is indicative of the paradox at the heart of the UK media-political-security service inception of the term radicalisation in the 2000s. This is their characterisation of a terrorist threat from young Muslim men as potential terrorists that is ubiquitous, i.e. any one person could potentially be radicalised and thus pertains to a ‘whole generation’, and yet only ‘a few among a generation’ have been found to commit or plot to commit violent acts (in this context routinely described by the same media-political-security services as ‘terrorist’).

In this way, the use of the term radicalisation is an ideal extension of the media, political and security services discourses of the incalculable scale and other parameters of the threat posed by twenty-first century terrorism. Furthermore, this points to the minimal prospects for ever attaining precision in terms of the proportionality of response to or pre-emption of a threat conceived in such an imprecise and non-scalable term.

And what the extract above reveals is that the term ‘radicalisation’ no longer serves those who one would think were (at least initially) its very purveyors. And so, the former Director of MI5, who was absolutely pivotal to the former government’s counter-terrorist strategy in which the countering of ‘radicalisation’ was a central plank, shows unease even in using the term.

Here then we can talk not just of the slippage of radicalisation in terms of its meaning and usage, but of its slippage from the hands of its former would-be masters. Radicalisation has been unleashed, it has, so to speak, ‘gone wild’. And it is the ‘going wild’ of the central UK counter-terrorist agenda constructed around radicalisation, that this book takes as its problematic. This is not just a matter of the exploration of a set of somehow detached media and government discourses speculating and attempting to pre-empt the nature and varying degrees of the threat posed by terrorism and other twenty-first century risk. Rather, the emergence of radicalisation is a sign of a new pervasive mediatised condition of ‘hypersecurity’ (Masco 2006; Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010a).

This condition marks a shift from a relatively institutionalised (i.e. via mainstream broadcast media) and ordered discursive regime of terror threats to one characterised by an emergent ‘contingent openness’ (Urry 2005: 3). And yet, at the same time, seemingly paradoxically, there occurs a reflexive institutionalisation of this very contingent openness of terror in and of the contemporary era through attempts to demarcate and control perceived and potential security threats by those charged with the protection of the many. It is these attempts to ‘make terror at least governable’ according to Michael Dillon, that spawns a ‘radical ambiguity’: ‘western societies themselves governed by terror in the process of trying to bring terror within the orbit of their political rationalities and governmental technologies’ (2007: 8).

Radicalisation, we are suggesting here, is both symptom and cause of the state of hypersecurity, which is an optimum candidate for what Dillon (ibid.) proposes, namely a ‘double-reading’ of terror. And so it is with the intangibility of ‘radicalisation’: it feeds a state of hypersecurity through the term’s glossing over of any coherent and generalisable explanation in terms of why, when and how individuals become ‘radicalised’. There is no reliable prescription that can account for the so-called ‘journey’ of stereotypically disenfranchised and disaffected young British Muslim men (or anyone else for that matter) from citizen to terrorist.

Moreover, the traditional targeting of an ‘enemy’ as previously understood as a meaningful requirement for the constitution of a threat is divested under the conditions of hypersecurity. Rather, it is more the case that the notion of ‘enemy’ has been replaced with the threat itself, something that Frank Furedi, for example, considers is ‘a threat beyond meaning (2007: 77). Radicalisation in the UK but also elsewhere across Europe, has quickly emerged as a tangible, intangible threat, feeding into the radical ambiguity of the construction of and responses to ‘terrorism’ and particularly in the UK following the 2005 London bombings.

In what follows we interrogate the emergence and the mediatisation of radicalisation, as a discursive frame that has ‘gone wild’ in escaping the very parameters its deployment was intended to control, or at least be seen to control.

Box 1.2 Defining radicalisation

The OED defines ‘radicalisation’ as: ‘The action or process of making or becoming radical, esp. in political outlook’2 and ‘radical’ as: ‘Polit. Advocating thorough or far-reaching political or social reform; representing or supporting an extreme section of a party.’3 In fact to trace a genealogy of the term is to reveal its application to having a certain strength of character, in espousing radical principles in UK and US eighteenth and nineteenth century politics, for example. Yet, it is in the twenty-first century that radicalisation has suddenly emerged in its least-benign form as a key concern of policymakers, security services, and journalists, notably as a threat to the stability and security of countries around the world. Radicalisation, to these groups, is often constructed as a process which a person (or persons) undergoes that may result in their committing violent, and moreover, ‘terrorist’ acts. Put another way: radicalisation today is seen as: ‘The phenomenon of people embracing opinions, views and ideas which could lead to acts of terrorism’ (emphasis added).4

To provide another example, this time taken from the Netherlands ‘National Coordinator for Counterterrorism’ (2007: 91):

Again, the criticality of the ‘end point’ of radicalisation is in its resulting in a violent act. Given it is very difficult to attribute beginning and ending points and any other generalisable characteristics and effects to the process of radicalisation, its identification and pursuit as a security threat for government, directly feeds hypersecurity, as we have already set out.

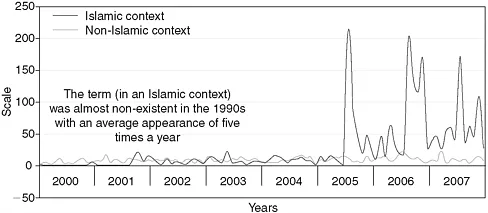

From the above definitions, the heavy qualifications are immediately apparent, and are indicative of the highly speculative nature of the discourses on security threats in the opening decade of a century already marked with what is often presumed to be a ‘series’ of terrorist attacks which have been intensely and extensively reported. To give just one example from the UK: Figure 1.1 reveals the sudden engendering of the term ‘radicalisation’ in the British press in its Islamic context. This followed the 7 July 2005 (‘7/7’) London bombings in which four suicide bombers killed 52 and injured more than 770 people in co-ordinated attacks in central London, and the attempted bombings again in London two weeks later. Yet radicalisation as a discernible cause of this or other terrorist atrocities at the same time appears to be tenuous at best, So, as the official House of Commons report into the London Bombings concluded, for at least three of the four 7/7 bombers, ‘there is little in their backgrounds which mark them out as particularly vulnerable to radicalisation’ (Home Office 2006: 26). The considerable difficulties in both identifying someone who has undergone a process of radicalisation and also those likely to become radicalised does appear to render the term as employed by those charged with counter-terrorist strategies and operations, as not particularly useful. What explanations are there then for the establishment of the term radicalisation in security discourses and what function does it perform and for whom?

The emergence of radicalisation: the new media ecology

The answers to these questions this book situates in the study of contemporary security in a ‘new media ecology’ (Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010a; cf. Cottle 2006; Fuller 2007; Postman 1970). This is the current rapidly shifting media saturated environment characterised by a set of somewhat paradoxical conditions, of, on the one hand, ‘effects without causes’, in Faisal Devji’s terms (2005), yet, on the other, a profound connectivity through which places, events, people and their actions and inactions, seem increasingly connected. So, for example, Hoskins (2011) identifies a ‘connective turn’, as the ‘massively increased abundance, accessibility and searchability of communication networks and nodes, and the seemingly paradoxical status of the ephemera and permanence of digital media content’.

There are a number of cross-cutting and in some ways convergent accounts of the characteristics of the new media ecology across the social sciences and humanities. A resurgent term that is particularly useful in exploring the relationship between media and radicalisation in terms of the mapping out of its presence and influence in security discourses is the idea of ‘mediatisation’. Stig Hjarvard is one of the most influential proponents of the term. He writes of the mediatisation of society itself and defines this as:

War and conflict, education, business practices, family life and other social realms today, to differing extents, are not simply mediated (relations sustained via media as medium); they are actually dependent upon media and, consequently, have been transformed to increasingly follow media logics; they are mediatised.

Across much of the advanced and developing worlds there are few times and spaces that can be conceived of as existing ‘outside’ of the new media ecology. But across new media studies there are emergent a range of positions along an axis of mediation – mediatisation with different scholars positioning social, political and cultural phenomena as embedded in or subject to media logics to varying extents (see Couldry 2008; Livingstone 2009). Crucially, this also involves a broadening and a deepening of the ...