![]()

1

Frontiers of Research on Social Communication: Introduction and Overview

Klaus Fiedler

Language is an anonymous, collective and unconscious art; the result of the creativity of thousands of generations. (Edward Sapir)

The Social Psychology of Communication: A Neglected Topic

The present volume in the “Frontiers” series is devoted to the fascinating topic of social communication. Although communication is ubiquitous – according to Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson’s (1967) aphorism, one cannot not-communicate – and genuinely social, or interpersonal, there is a long tradition of neglecting this topic in social psychology. A glance at the table of contents of major textbooks, journals, and handbooks reveals that research and theorizing on communication phenomena are conspicuous for their scarcity. Whereas other areas such as social cognition, intergroup and intragroup processes, cross-cultural relations, prosocial and antisocial behavior, and judgment and decision making have been flourishing for decades, there is still a paucity of interest in language and communication processes.

To be sure, genuine communication topics are sometimes treated under different cover. Persuasion is often conceived as a process of attitude change, within the dominant realm of social cognition. Self-presentation appears as a social motive rather than a skill in symbolic interaction. Conducting interviews is commonly understood as a methodological problem, group discussions are conceived as rational decision processes, and stereotypes are defined as intra-memory representations rather than inter-memory rumors and messages. Language, the most important and refined symbol system for communication, is almost totally missing from social psychological theorizing, just as non-verbal communication is mainly confined to emotional and clinical research topics. Linguistic and communicative rules per se, as a research end in itself, as explanatory constructs for understanding social psychological phenomena – such as attribution, affiliation, conflict, deception, or discrimination – have received remarkably little attention.

How can this relative exclusion of genuine communication research from social psychology be understood? What may account for the fact that hardly any textbook on social psychology includes a chapter on language, the most prototypically social behavior one can imagine? There is no one and only comprehensive answer, to be sure, to historical questions such as these. However, one reasonable explanation for the minimal role played by lexical, syntactical, and pragmatic factors in the flourishing domain of social psychology is that other theory metaphors have dominated this field from the beginning, such as Lewin’s (1943) field theory, Festinger’s (1954, 1957) homeostatic notions of dissonance reduction and uncertainty reduction through social comparison, Bruner’s (1957) categorization paradigms, Hovland’s social-cognitive behaviorism (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953), and more recently the advent of statistical metaphors (Gigerenzer, 1991; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), and the new interest in unconscious processes (Hassin, Uleman, & Bargh, 2005; Uleman & Bargh, 1989). Maybe, the theoretical potential of linguistic and genuinely interpersonal, interactionist concepts was just overshadowed by the power of these other, extremely successful theoretical approaches.

However, one has to acknowledge, too, that conceptual underpinnings for a fruitful social psychology of communication have never been missing. Fascinating conceptual frameworks and seminal theoretical papers have always been there, such as Karl Bühler’s (1934) organum model, George Herbert Mead’s (1934) symbolic interactionism, Skinner’s (1957) generalized behaviorist approach to verbal behavior, Allport and Postman’s (1948) work on the psychology of rumor, Bartlett’s (1932) serial reproduction paradigm and his famous work on narratives and cultural transmission of knowledge, or Hovland, Janis, and Kelley’s (1953) early work on persuasion. More recently, leading scholars and social psychologists have afforded highly elaborated frameworks, guidelines, and working hypotheses for fruitful communication research. Prominent examples of these seminal contributions are Clark (1985), Clark and Schober (1992), and Krauss and Fussell (1996). However, in spite of all these strong ideas and affordances, there has been a paucity of similarly industrious paradigmatic research as in social cognition or intergroup relations. What has been missing, primarily, is the growth of influential paradigms for empirical research, which have to complement and fertilize attractive and challenging theories and methodological conceptions.

Fortunately, this situation may now be changing gradually. A number of fruitful paradigms have emerged during the last two decades, gaining considerable impact on the social psychological literature. Delineating the progress of research in these promising paradigms is the shared purpose of the chapters included in the present volume. They represent the frontiers, as it were, of current paradigmatic research on social communication.

Diversity of Communication

Organizing and integrating these diverse developments are demanding tasks, because research reflects the complex and adaptive nature of the very phenomenon of communication. The form and substance of this multi-faceted, dialectic phenomenon are changing permanently. Communication is for being understood and for being misunderstood, to convey old word meanings and to create new meaning, to tell it as it is and to fabricate lies that conceal what is, to solve problems and to create new problems and conflicts. Not only are the motives and goals of communication manifold, but also the rules, means, channels, and the available symbol systems. There is hardly any form of expression that cannot be included in the phenomenon called social communication. That is, hardly any accent, dialect, artificial language code or jargon, any deformation of language, cryptic metaphor, irony, or intentional violation of grammatical rules could undermine interpersonal communication. It still functions to a remarkable degree, as easily evident from a glance at Internet chatrooms, lonely-hearts ads, or Dadaistic and surrealistic arts.

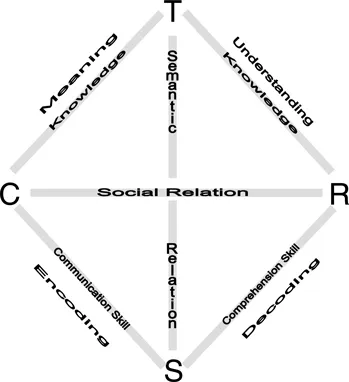

Given this lively and multi-faceted nature of communication as a research topic, it is no surprise that the frontiers in communication research cannot be located on a single dimension or plane. More dimensions are needed to get an overview of current research developments. Nevertheless, for an overview, or advanced organizer, it ought to be possible to impose some structure on the investigation of social communication by simply considering the structure of the phenomenon itself. In Figure 1.1, social communication is portrayed as a process that involves four parts: a communicator C, a recipient R, a topic (or reference object) T, and a symbol system S. This diagram can be understood as an extension of Bühler’s (1934) triadic organum model (encompassing only C, R, and T), which even after almost a century is still modern and relevant to the frontiers of social communication research in the year 2007.

The lines connecting these four constituents in Figure 1.1 correspond roughly to the components of the communication process. The link from C to S represents the “encoding” process whereas the link from S to R is labelled “decoding”. The link between the two animate roles in the communication game, C and R, is a social relationship, whereas the relation between S and T is semantic in nature, in that S provides an arbitrary symbol that can be used as a substitute of the meaning of T, prompting a plethora of extra-linguistic world knowledge about the target topic T. Thus, by drawing on shared knowledge about T, the communicator C uses symbols S to invite the communication partner R to “understand” what C “means” concerning the communication topic T (cf. Figure 1.1).

Beyond Encoding and Decoding

One important point conveyed in Figure 1.1 is that interpersonal communication must not be reduced to processes of encoding and decoding of linguistic symbol strings. Rather, social communication is embedded in extra-linguistic functions motivated by goals and instrumental plans to achieve those goals, serving such pragmatic functions as persuasion, bargaining, dating, instruction, deliberation, and flattery. The ultimate goal of communicator C’s communicative actions is not just to enable receiver R to decode the symbolic message S as accurately and faithfully as possible, as in Shannon and Weaver’s (1949) classical information theoretical framework. Nor is the goal to conserve the logical truth value of the propositions inherent in S, as in propositional logic. Rather, the actual goal is for C to move R somewhere relative to a communication goal or reference topic T (e.g., move R to do someone a favor, to buy a product, or to come to a party or date, to share an idea or emotion, etc.). Communication (in its broadest sense) provides a generative tool to accomplish such interpersonal moves (cf. Rips, 1998). Language constitutes social actions (Austin, 1962).

Figure 1.1 General framework for the analysis of social communication processes.

Noteworthy, verbal language is more universal, more commonly available, and therefore more important a means of achieving social influence than other, more direct tools – such as physical power, legal enforcement, conditioning, or unexplained reward or punishment systems. The overly rich and versatile symbolic system of language is also more effective and more applicable a means than non-symbolic influences, such as imitation learning or environmental pay-off structures used to induce desired behaviors. For refined cultural information systems to work – such as school teaching, mail and telephone, advertising, negotiation, or mass media – language is virtually indispensable, whereas all other influence instruments are substitutable.

The nature of the various influence functions or communicative actions can vary in different respects: in the goal-defining topics (T), in the nature of the symbolic tools (S) used to construct a message, and in C’s intention regarding T, as well as the social relation between C and R. For instance, persuasion is a communicative function whereby C has a clear-cut intention to convince R of the correctness or usefulness of an attitudinal topic T, using symbols (S) that typically entail argument-like strings, but also heuristic or affective cues guiding inferences about T. The social distance between C and R, and their inter-dependence, status, or power relation can vary considerably in persuasion. Other communication acts, such as excuses or instructions, are constrained by specific relations between C and R. Excuses presuppose that C feels somehow guilty or indebted toward R, weakening C’s social exchange potential and restricting the appropriate means of reaching the topical goal T, namely, that R may forgive C’s previous behavior. Appropriate symbolic tools for excuses involve emotional expressions and selfreferent feelings of remorse and modesty gestures, rather than strong arguments or new epistemic information. Likewise, instruction applies to situations in which C’s knowledge exceeds that of R, or punishment is an action in which C exceeds R in power. The topical goals and the symbolic means vary accordingly.

For these and many other communicative functions to be applicable and effective, a number of premises have to be met (cf. Figure 1.1): C must be aware of her relation to R, of R’s knowledge and attitudes toward T, and R’s understanding of the symbols S; and R must interpret C’s intention vis-à-vis T, her position relative to C, and have knowledge about C’s knowledge and attitude toward T and about C’s mastery of the symbol system S.

To the extent that some of these conditions are not met, communication will not break down altogether. However, the process of communication can fail or suffer, or result in unintended outcomes. Whether such misunderstandings or unintended communication outcomes are always harmful or disadvantageous is still another question that should be answered with caution. It is indeed possible that in reality some misunderstandings, deceptions and self-deceptions, and illusions of understanding are themselves an integral and functional aspect of communication and social interaction. In any case, it is important to note that the communication game does not cease, but rather begins to become particularly interesting and consequential when its rational premises are not met, or are misunderstood. These are the situations that give rise to illusions and conflicts, deception and effective negotiation, flattery and insult, and humor and regret.

Inference Games

An obvious characteristic of communication processes – whether they are clearly structured and primitive or refined and sophisticated – is that both C and R must always go beyond the information given in the symbol string S. They must engage in all kinds of inferential activities. Speech acts or communicative acts are all about implicatures – speech acts that are to be actively inferred from utterances. This lesson is not only at the heart of Searle’s (1969) and Grice’s (1975) speech act approach and Wilson and Sperber’s (1995) theory of communication. We also meet here the natural home domain of mainstream social psychology: inferences of C’s intentions, dispositions, and causal attributions of former behaviors or current speech acts influencing R’s attitudes, retrieving information about T from memory, negotiating the relation between C and R, expression of emotions, and empathizing with one’s communication partner’s emotions, preferences, and goals. Effective social communication depends, first and foremost, on the communication participants’ ability to solicit and to understand such inferences beyond the encoded message, rather than merely sticking to the literal text of a message. In Austin’s (1962) terms, communication is not merely an “illocutionary act”; it rather has to be conceived as a “perlocutionary act”.

Inference games can take many different forms, depending on the underlying communication act. When C intentionally and instrumentally misleads R to draw erroneous inferences about T, such a planned communication bias is called a “deception”. When R does not naively buy the inference suggested by C but gathers background information about alternative inferences to be drawn, this meta-cognitive inference game can be called “lie detection” or “cheater detection”. When C wants to solicit T-related attitudes in R that C considers veridical and valid, this is “persuasion”. When C wants R to discard an invalid inference about T, we have a case of “debriefing”. When R’s inferences (do not) match the inferences that C intends to solicit, the inference game can be termed “(mis)understanding”.

Other games involve more specific inferences, such as “excuses” or “apologies”, in which C invites R to infer that C feels regret or guilt toward T; or “flattery”, in which C wants R to infer that C appreciates or admires R. “Ingratiation” is slightly different in that C has vested interests in letting R infer C’s appreciation. In “gossip”, to give another example, C provides R with inference-prone information about norm-relevant social behavior of target persons T.

A common denominator of all these diverse games lies in the fact that they load high on inferential activity. If the toolbox of language users were only equipped with devices for encoding and decoding literal text, or writing and reading a code, there would be no place for effective deception, irony, kidding, teasing, gossiping, sliming, amusing, or distracting others from an unwanted topic. Moreover, the communicative repertoire for such crucial speech acts as educating, effective teaching, explaining, encouraging, derogating, excusing, praising, blaming, punishing, asking favors, or for indirectly communicating respect, pride, love, approval, or contempt would be quite impoverished.

Preview of the Present Volume’s Contents

It is no surprise, then, that the frontiers of current research on social com...